Xi Jinping’s Visit to Myanmar: Implications for the Bay of Bengal

Atmakuri Lakshmi Archana, Yogesh Joshi

4 February 2020Summary

China’s intention to make inroads into the Bay of Bengal has become clearer with President Xi Jinping’s recent visit to Myanmar which will not only boost infrastructure projects in Myanmar but will also significantly increase China’s influence in the region.

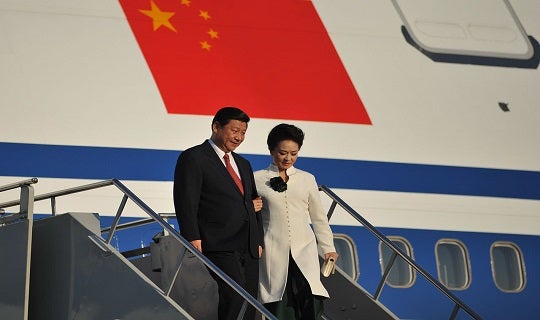

Chinese President Xi Jinping concluded a much-anticipated two-day visit to Myanmar on 17 and 18 January 2020. Among the 33 agreements signed during the visit, the development of a deep-sea port in Kyaukphyu on the shores of the Bay of Bengal, a railway project to connect Chinese province of Yunnan to Myanmar’s coastal cities, an inland-waterway through the Irrawaddy river and a mega-hydropower dam project are the most prominent. These projects are expected to re-energise the rather stale progress made under the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor so far.

Xi’s visit to Myanmar, the first by a Chinese president in almost two decades, has the potential to drastically alter regional geopolitics in the Bay of Bengal. Several domestic and geopolitical reasons underline Beijing’s outreach to Myanmar and its strategy to use it as a conduit to the Bay of Bengal. First, it will boost China’s presence in the Indian subcontinent. The deep-sea port project is intended to cement China’s geostrategic footprint in the Bay of Bengal. Second, China’s dependence on oil has been increasing by 6.7 per cent each year and the demand is set to increase further, given the trade war with the United States (US). Therefore, the Bay of Bengal is a good alternative route for China’s Malacca dilemma. China plans to use Myanmar as a strategic catapult into the Bay of Bengal and the larger Indian Ocean to further establish its presence in the region.

Being the conduit between the Western Indian Ocean and South China, the Bay of Bengal enjoys immense geostrategic heft in strategies of Asia’s rising powers. It is also a lynchpin of any successful Indo-Pacific strategy. If the Quad countries – the US, India, Japan and Australia – continue to push for a loose alliance against China’s increasing maritime power both in the Pacific Ocean and the Indian Ocean, China’s maritime ambitions could be easily thwarted. Beijing would like to pre-empt any such attempt by the Quad countries. Establishing its presence in the Bay of Bengal is, therefore, fundamental to sustain China’s inroads in the Indian Ocean Region (IOR). Cultivating Myanmar as a strategic partner serves three major objectives in China’s Indian Ocean strategy.

First, China’s development of Kyaukpyu port will further entrench its naval presence in the IOR. On the pretext of developing infrastructure and connectivity under the Belt and Road initiative, Beijing has developed a myriad of naval posts across IOR – from Gwadar port in Pakistan to Djibouti in Africa and the most recent naval outpost in Cambodia. However, the militarisation of the Kyaukpyu port will be a game-changer as China will get a military toehold in the Bay of Bengal. Though the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) Navy is highly active in the waters of the Bay of Bengal, it still lacks military infrastructure and logistics support in the region.

Second, the Andaman Sea and Bay of Bengal are fast becoming a new flashpoint in Sino-Indian strategic maritime competition. In the last two years, PLA Navy entered the Bay of Bengal on several occasions with the most recent incident in December 2019 when a Chinese vessel entered India’s special economic zone without permission. The frequency of Chinese submarine patrols in the IOR has almost tripled in the last two years. Although the past interventions were criticised under violations of United Nations Convention for the Law of the Sea, China will now have a legitimate reason to be present in the Bay of Bengal because of its presence in Myanmar.

Third, Myanmar is a key influencer for China’s ambitions in the Indian Ocean. It is not only a gateway to the Bay of Bengal but is also a strong member of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). While the Western nations continue to isolate Myanmar on its human rights track record, China’s policy of non-intervention in Myanmar’s domestic politics has helped it to cultivate goodwill in Naypyitaw. China also provided military support to Myanmar. By keeping Myanmar on its side and by building such economic dependencies, Beijing hopes not only to keep India on its toes but also create enough influence within ASEAN.

For New Delhi, securing the Indian waters is of utmost priority which otherwise would intensify maritime security dilemma. India’s first largest naval exercise, Milan, in the Indian Ocean later this year (excluding China) is highly significant to reiterate its importance in the Bay of Bengal. Yet, India has been complacent in confronting this new geostrategic reality. One of the reasons for New Delhi’s relatively weak stronghold is the lack of economic might.

Recognising this, New Delhi is partnering the Quad countries to boost maritime security in the Bay of Bengal. Japan has been funding infrastructure projects, including port development in Myanmar and Bangladesh with India. The US and India jointly held the Malabar naval exercise in the Indian Ocean in 2019. Washington laid out a clear military roadmap in the Indo-Pacific to not only boost military activities in the IOR but also to build India’s maritime security capabilities.

Additionally, New Delhi could rekindle maritime ties with ASEAN. This will reduce the collective concerns regarding the security of the Bay of Bengal and the Indian Ocean. Recently, India, Singapore and Thailand held a joint trilateral maritime exercise for the first time to cooperate on the security and maritime issues in the Bay of Bengal. However, ASEAN and India can do more by partnering with Vietnam and the Philippines.

Ms Archana Atmakuri is a Research Analyst at the Institute of South Asian Studies (ISAS), an autonomous research institute at the National University of Singapore (NUS). She can be contacted at isasala@nus.edu.sg. Dr Yogesh Joshi is a Research Fellow at the same institute. He can be contacted at isasyj@nus.edu.sg. The authors bear full responsibility for the facts cited and opinions expressed in this paper.

-

More From :

More From :

-

Tags :

Tags :

-

Download PDF

Download PDF