Summary

Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi’s visit to India in August 2025 signalled the end of a period of thaw and the beginning of a more active rapprochement between the two countries. It also marked a partial return to the pre-2020 approach to the border dispute, though with important new nuances. At the same time, China’s position in relation to India has become stronger. Lastly, fundamental dualism at the heart of their relationship has reasserted itself.

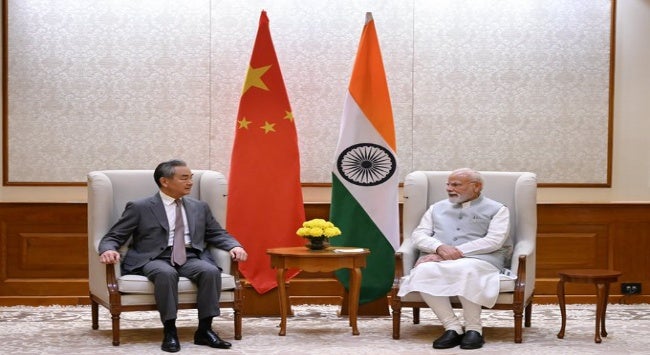

Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi’s visit to India on 18 and 19 August 2025 marked a significant step to improving China-India relations, highlighted by his meeting with Prime Minister Narendra Modi. The visit witnessed the establishment of new mechanisms to deal with the contested border, reported Chinese promises to lift economic restrictions on India, and the announcement of Modi’s visit to China for the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) leaders’ summit in Tianjin in end-August 2025.

There are four major takeaways from the visit. First, the visit marked the end of a period of thaw between the two sides and paved the way for more active rapprochement. This thaw, which started in October 2024, was aimed at overcoming the effects of their 2020 border crisis, stabilise the situation along the border and bring back normalcy to their relationship. While these tasks have largely been accomplished, de-escalation along the border still has some way to go while de-induction is even farther away.

Modi’s visit to China is likely to herald the next phase of rapprochement. It will likely focus on the development of economic relations and closer cooperation in international platforms such as the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa). The goals would be to diversify Beijing and New Delhi’s trade and foreign policies, hedge against growing global instability and strengthen China and India’s bargaining positions vis-à-vis Washington.

Second, the renewed commitment to resolving the boundary dispute signalled a partial return to the pre-2020 approach, which aimed to compartmentalise the issue by placing negotiations on a separate track from broader bilateral relations. Substantively, this means a focus on bureaucratic procedures, expert-level engagement and bilateral mechanisms, alongside cooperative border management to prevent incidents and escalation. While this signals a return to structured dialogue, the approach is slow and cumbersome, often creating simulated progress without tangible outcomes. The lack of political will, particularly on the Chinese side, is the key reason.

The two sides might adopt a sectoral rather than a packaged approach to settling their dispute – an approach often linked to concluding ‘early harvest’ agreements along the border. However, interest in such an ‘early harvest’ is not new and has not yielded results before. Such agreements likely concern the least contested sections of the border, the middle sector and the Sikkim border. Moreover, the two sides floated a return to the 2005 Political Parameters and Guiding Principles agreement, a longtime Chinese demand. Theoretically, this might constitute a gain for India as the agreement implied that China would accept Indian sovereignty over most of Arunachal Pradesh. However, it is unclear what a return to the 2005 agreement would entail and how substantive its resurrection would be. Furthermore, the original agreement began unravelling almost immediately.

Third, China’s position vis-à-vis India has strengthened, although it is less than what some Chinese observers think. The recent crisis in United States (US)-India relations has disrupted New Delhi’s carefully balanced foreign policy, weakened its strategic position relative to Beijing and prompted it to engage more actively with Beijing and Moscow to regain leverage with Washington. India’s acceptance to delink the development of bilateral relations from progress along the border is an indication of the change in its attitude towards China. The timing of Wang Yi’s visit and Modi’s decision to accept the invitation to attend the SCO leaders’ summit are also likely related to these dynamics.

Nevertheless, Beijing’s advantage over New Delhi should not be overstated. India is likely to withstand the pressure of President Donald Trump’s tariffs, and China is unlikely to offer meaningful economic relief in the near term. Moreover, the unpredictable nature of the Trump administration means that neither the current US-China truce nor the present US-India tensions are guaranteed to last.

Finally, the fundamental dualism at the heart of the China-India relationship has reasserted itself after five years of confrontation. Throughout the last three decades or so, China-India relations have been characterised by a frequent shift between cooperation and competition, which has resulted in uncertainty about the future of their relationship.

The events immediately following Wang Yi’s visit to India highlight this dualism. After New Delhi, Wang attended a China-Afghanistan-Pakistan trilateral meeting in Kabul to discuss extending the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor to Afghanistan, which India fiercely opposes, and then proceeded to Islamabad. The same day, during a visit to Chinese Tibet, President Xi Jinping praised the huge Yarlung Tsangpo dam, a major concern for India. On its part, after the visit, India successfully tested its Agni-5 missile that can reach any part of China.

Wang Yi’s visit to India signalled a partial return to normalcy in China-India relations, marked by renewed engagement, familiar approaches to the border dispute and the reappearance of the relationship’s characteristic dualism. Still, things are not as they were before 2020. Trust has eroded, the legacy of the border clashes lingers and global dynamics – shaped in part by Trump’s policies – now favour China. Despite this, ties are likely to improve further, with Modi set to visit China at the end of August 2025.

. . . . .

Dr Ivan Lidarev is a Visiting Research Fellow at the Institute of South Asian Studies (ISAS), an autonomous research institute at the National University of Singapore (NUS). He can be contacted at ivanlidarev@nus.edu.sg. The author bears full responsibility for the facts cited and opinions expressed in this paper.

Pic Credit: X

-

More From :

More From :

-

Tags :

Tags :

-

Download PDF

Download PDF