Summary

On 30 November 2019, the Maha Vikas Aghadi (MVA) – a coalition of Shiv Sena, the Nationalist Congress Party and the Indian National Congress – proved its majority in the Maharashtra Assembly, with Uddhav Thackeray being appointed chief minister. The run-up to government formation is Maharashtra was an illustration of the frailties of Indian democracy. A full term for the MVA government is also by no means assured.

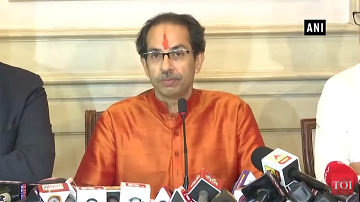

After nearly a month of uncertainty, Maharashtra has a government in place. On 30 November 2019, the Maha Vikas Aghadi (MVA) – a coalition comprising Shiv Sena, the Nationalist Congress Party (NCP) and the Indian National Congress – proved its majority in the Maharashtra Assembly with the support of 169 out of 288 members. The formation of the MVA would have been unforeseen when the Maharashtra election results were announced on 24 October 2019. The chronology of events since the election result is symbolic of the uncertainties and vicissitudes of Indian politics.

The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and Shiv Sena, who were pre-election allies, won 105 and 56 seats respectively, which was comfortably above the majority mark in the Maharashtra Assembly. The NCP won 54 seats and the Congress 44. However, things took a dramatic turn when Shiv Sena pulled out of the alliance after the BJP rejected its demand of rotating the chief ministership. On 8 November 2019, the two parties broke off of their alliance. Since no party was able to muster the numbers to form the government, President’s Rule was imposed on 12 November 2019.

Ten days into President’s Rule, Shiv Sena, along with the NCP and the Congress, announced that it would stake claim to form the government with Shiv Sena’s chief, Uddhav Thackeray, as chief minister. Events took yet another unexpected turn when, in the early hours of 23 November 2019, the outgoing chief minister, Devendra Fadnavis, took oath as chief minister claiming support of a breakaway NCP faction, led by Ajit Pawar, the nephew of NCP chief, Sharad Pawar. The NCP, however, claimed that Ajit did not have the support of the majority of the NCP legislators and, subsequently, the MVA moved the Supreme Court. The apex court ruled that a trust vote must be held on 27 November 2019, which led to Fadnavis’ the resignation.

The tortuous sequence of events in Maharashtra has laid bare some of the systemic weaknesses of Indian democracy. It has also signalled some important shifts in Indian politics. Political opportunism and the absence of ideological commitments were on display in Maharashtra. While the BJP-Shiv Sena combine won the popular mandate on the basis of a pre-poll alliance, Shiv Sena did not hesitate to set aside voter sentiments by parting ways with the BJP. The Congress and the NCP, which fought a bitter electoral battle against Shiv Sena, also had no qualms in eventually tying up with it.

However, what was more pernicious than the coming together of rivals post-election was the BJP’s grab for power in the wee hours of 23 November 2019. The partisan role played by the Maharashtra governor in swearing in Fadnavis was a poor advertisement for Indian democracy. That the prime minister and the home minister were complicit in this act, which was swiftly overturned by the Supreme Court, was an acute embarrassment for the BJP.

Leaving aside the corrosive impact of the events in Maharashtra on Indian democracy, some of the key political takeaways from the month-long political drama in Maharashtra were the following.

First, the loss of Maharashtra was a blow to the BJP, coming so soon after its overwhelming victory in the 2019 general election. Maharashtra is not only the second most populous state in India, but it also generates the highest amount of political funds. The BJP’s performance in the Maharashtra Assembly election itself was worse than expected. The party had talked of getting an absolute majority on its own. Instead it fell short of a majority, dropping from its 2014 tally of 122 seats to 105. The results were an illustration that state elections have their own narratives and Modi’s vote-catching abilities are much more limited compared to general elections. The results were also an indication that national issues, such as the abrogation of Article 370 in Kashmir, do not have the kind of resonance in Assembly elections that the BJP might be hoping for. Beyond the actual results, the perils of the BJP’s strategy to capture power at all costs was exposed.

Second, the break-up of Shiv Sena-BJP alliance, which goes back three decades, is likely to have an impact on the BJP’s other allies. Coming elections in states such as Bihar could well see BJP allies like the Janata Dal (United) and Lok Janshakti Party getting emboldened. For Shiv Sena, tying up with the Congress could signal a more centrist approach and a turning away from its anti-Muslim rhetoric.

Third, the way Sharad countered the BJP and masterminded the formation of the government showed that, so long as he is around, the NCP will remain a major player in Maharashtra. Sharad’s example will also give hope to other regional parties as they battle the BJP’s dominance.

Though the MVA has proven its majority, there are several question marks on the new government in Maharashtra. Whether the three parties, which are in alliance, can manage their differences remains to be seen. One of the immediate issues will be the allocation of ministerial portfolios. As of now, along with Chief Minister Thackeray, six cabinet minister have been sworn in. While the new speaker of the Maharashtra Assembly is from the Congress, the deputy chief minister’s position, which will be occupied by the NCP, is still undecided. While Ajit remains keen on the deputy chief minister’s chair, whether Sharad will decide on another leader such as Jayant Patil remains to be seen. On the ideological front, Hindutva and its prominence is likely to remain a thorny issue between Shiv Sena and the Congress.

Finally, the BJP, having failed to form the government, will try its best to topple the MVA at the earliest opportunity. As in Karnataka, where an opposition alliance collapsed after 14 months due to legislators defecting to the BJP, there is no guarantee that the MVA government will last its full term.

….

Dr Ronojoy Sen is Senior Research Fellow and Research Lead (Politics, Society and Governance) at ISAS. He can be contacted at isasrs@nus.edu.sg. The author bears full responsibility for the facts cited and opinions expressed in this paper.

-

More From :

More From :

-

Tags :

Tags :

-

Download PDF

Download PDF