Summary

The global pandemic has reiterated the importance of strong and resilient health systems, ensuring that all societies enjoy universal and affordable access to healthcare services. This paper argues that efforts to sustain universal health coverage are contingent on governments navigating five key challenges – adequate resourcing; calibrating the design of health systems; working within existing institutions; dealing with entrenched and competing interests; and barriers in the implementation of health reform.

Introduction

Over the past two decades, most governments in Asia have made important strides in their efforts to achieve universal healthcare. Healthcare has been a focus of policy reforms in the region[2] not only in low-middle-income countries such as India and Indonesia but equally in the high-income economies of Singapore and South Korea.

These efforts have contributed to improving health outcomes, better access to health services, and, importantly, lowering out-of-pocket (OOP)[3] spending on healthcare. The OOP expenditure on healthcare – the amount that individuals pay (for which they are not reimbursed) in accessing health services – is a metric to measure the financial protection that health systems offer. High OOP spending can reduce access to needed services and, in some cases, pushes vulnerable households into poverty[4] or force families to borrow or sell assets to pay for medical expenses. China[5] and Singapore,[6] for example, have reduced OOP spending on healthcare by more than 50 per cent, and Thailand from 30 per cent to less than 10 per cent[7] over the past two decades. India has made similar gains in reducing maternal mortality rates.[8]

Notwithstanding these advances, there are several challenges in sustaining universal healthcare: healthcare costs are rising rapidly, public health systems are overwhelmed, existing healthcare infrastructure is stretched and medical supply chains are fragmented.

Resourcing

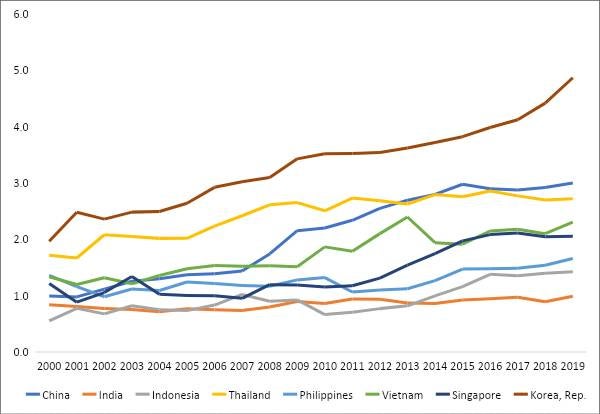

Achieving universal healthcare requires levels of public spending to which very few governments have been able to commit. Public spending on healthcare in most of the low-middle income countries in the region (India, Indonesia, Philippines and Vietnam, for example) has hovered between one to two per cent of gross domestic product (GDP) over the past two decades. Most of this spending is allocated to recurrent expenditures leaving limited room for investing in other priority areas such as public health or programmes to manage infectious diseases. After decades of policy neglect or deliberate efforts to rely on markets in healthcare, most countries in the region have come to rely on the private sector to finance healthcare. Most of this private financing is without sufficient risk-pooling such as insurance programmes and is paid for directly by households through OOP payments. In some instances, these have pernicious effects in the case of severe illnesses,[9] including pushing vulnerable families into poverty.

Overcoming this sustained reliance on private financing requires governments to ramp up public spending on healthcare and many in the region have: Singapore’s spending on healthcare has increased significantly over the past 10 years. It now spends about six per cent of GDP on healthcare, about half of which is publicly funded[10] – a far cry from the meagre three per cent in the early 2000s.[11] China is another example. While total health expenditures have not changed drastically (about five per cent of GDP), public spending on healthcare now accounts for about half – a dramatic increase from 20 per cent in the early 2000s. Many other countries, however, find it challenging to meet their commitments. For instance, expanding India’s flagship universal coverage programme[12] for the 60 per cent of the population currently not covered is fiscally tenuous. Similarly, while Indonesia has announced the removal of differentiated subsidies that its members received, the program does not cover pharmaceuticals[13] which are a key driver of the OOP spending.

Further, the pandemic changed the distribution of public spending. Governments are rightly focussed on shoring up their public health systems and meeting vaccination and pandemic preparedness goals. A recent report by the World Bank[14] highlights that in many low and lower-middle-income countries increased levels of public expenditure on healthcare are unlikely to continue in the face of diminished fiscal space[15] and shallow economic growth.

Figure 1: Government Expenditure on Healthcare (% of GDP)

Source: World Development Indicators

Note: There is a three-year lag on comparable data on health expenditures.

Policy Design

The second struggle relates to getting the ‘right’ design that underpins universal coverage programs. Essentially, realising universal coverage requires governments to achieve goals that are not easily reconciled. Governments are expected to design a healthcare system where citizens have universal access to medical services and to ensure that healthcare providers remain responsive to patients’ needs at a cost that is affordable to society. This is challenging, as different stakeholders prioritise these goals differently. Governments and third-party payers such as insurance companies are rightly concerned about moderating healthcare costs. Patients and providers prioritise responsiveness, immediacy and quality of care, but do not want to shoulder the costs. These competing preferences are not easily reconciled.

An example is the relatively straight forward issue of paying healthcare providers. Governments rely on a combination of fee for service (when providers are paid for each service they provide); capitation (when providers receive a fixed amount per person they treat); diagnostic-related-groups (when providers are paid a fixed amount based on the patient’s symptoms and diagnosis); and block grants (lump-sum grants from the government) for different types of health services. Each of these offers fundamentally different incentives to control healthcare costs, and for being responsive to patients’ needs. Achieving both goals, therefore, require governments to use different types of payment tools to ensure that they work in concert.

This is again not easy to do – it requires access not only to disaggregated data on healthcare costs, demographic and epidemiological parameters, but also the capacity to use this data and inform policy. This is an arduous policy not helped by limited resources. For example, Medicare in the United States, which covers 40 million beneficiaries, is administered by a staff of 6,000 personnel with expertise in health administration. In contrast, the number of state-level personnel administering India’s health programme is 42 in Uttar Pradesh, which has a population of 200 million, and 10 in Bihar, which has a population of 100 million.[16]

International organisations such as the World Bank and the World Health Organization have been instrumental in shoring up capacity,[17] but there often remains a large gap between policy aspirations and actual policy practice. In the Philippines, for example, PhilHealth has been unable to fully implement its policy of ‘no balance billing’, where hospitals charge patients a nominal amount despite receiving subsidies. However, all is not bleak on this front. Thailand’s investments in building research capability[18] in its domestic health policy community in the early 2000s, has been central to adjusting the design of its flagship universal coverage scheme. India’s National Health Authority, the steward responsible for the government’s universal coverage programme, has introduced a range of measures to collect and share data on costs and insurance claims.

Institutions

A related issue is the constraints imposed by existing institutions in the sector. Institutions refer to formal organisations such as government agencies or private corporations involved in the sector, but also to establish arrangements to organise healthcare such as Medisave in Singapore, PhilHealth in the Philippines or the Employees State Insurance Corporation (ESIC) in India. These institutions are shaped by deeply held ideas and entrenched interests which constrain options available to policymakers when designing universal coverage programmes. For example, social insurance programs such as PhilHealth and Vietnam Social Security continue to exist despite extensive informal employment in their respective countries, which makes these insurance programs poorly suited to achieving universal coverage.[19] Similarly, the ESIC in India continues to exist despite a sustained track record of poor performance.[20]

The larger point is that policy efforts to achieve universal coverage reforms have to navigate existing institutions that operate in the sector. These institutions have a certain inertia which often slows down reform efforts. Elections and even unexpected crises can temporarily lower these barriers[21] and create an environment that is conducive to introducing new programmes.

Efforts in India such as its universal healthcare plan, Ayushman Bharath, or the Universal Coverage Scheme in Thailand are rare examples introduced after large electoral successes.

Most governments instead patch and layer existing programmes, which create challenges for policy coordination. For example, India’s 2008 health policy reforms resulted in a new programme anchored in the Ministry of Labour rather than the Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, raising issues for coordinating policy. The programme was transferred to the health ministry in 2015.

Politics

The institutional impediments echo the political struggle for universal healthcare. This stems from asymmetric power relationships, an example of which is the dominance of healthcare providers such as hospitals and doctors’ groups in the healthcare system. The doctors’ role in diagnosing illness and prescribing treatment confers political power to providers which is used to resist any policy effort that erodes their material interests and undermines their professional autonomy. While they may compete individually for patients, they are bound together around the broader purpose of maintaining their material interests.

Universal coverage programs invariably involve changes to how healthcare providers are paid – moving them from retrospective payments (where providers are paid after treating patients, the most common example of which is a fee for service) to prospective payments (where providers are paid a fixed amount such as salaries or capitation). Such efforts are typically resisted by providers and provider groups if they undermine their interests.[22] Even governments with high political legitimacy, and publicly owned health systems such as in China, have found it challenging to introduce prospective payment reforms in the wake of opposition from provider groups.

Providers are only one of the dominant stakeholders. Other groups such as labour unions and large insurance companies that underwrite health programmes can stall reforms that undermine their interests. Raising resources for financing healthcare often through higher taxes or surcharges or asking citizens to pay more to access healthcare services are intertwined deeply with domestic politics about the distribution of scarce public resources. Overcoming resistance from interest groups, and engendering support across diverse and disparate stakeholder groups is central to the political struggle around universal healthcare.

Implementation

There are challenges around coordination as well as working across different levels of government and across government agencies. Economics scholar Qian Jiwei, in his analysis of health policy agencies in China, estimates[23] that there are at least 11 ministries actively involved in the delivery of services with overlapping responsibilities, which delays decision-making and creates multiple veto points. Similarly, a study published by the National Institute of Public Finance[24] in India found that in the state of Bihar, transferring funds from the federal agency to the state-level implementing agencies required clearance by 32 ‘desks’ which led to delays in the delivery of funds of almost 12 months. The sheer scale of universal coverage programmes in India and Indonesia – about 250 million in Indonesia’s BPJS Kesehatan[25] (Social Security Agency on Health) and 500 million in India’s Ayushman Bharath – present administrative hurdles to overcome exclusion and inclusion errors, especially in populations with large informal employment.

Another operational struggle for universal healthcare relates to the lack of robust health information systems and disaggregated demographic and epidemiological databases. These are central to generating data and evidence for the design of universal coverage programmes. While there have been advances in developing these databases, progress has been patchy and uneven. For instance, in some states in India, only 25 per cent of deaths are registered in official records.[26] The absence of such essential data reduces the efficacy of any social policy programme.

Where to from Here?

Every country in the region is at a different stage of its journey but they face some common hurdles. In the high-income economies of Singapore and Hong Kong, recent policy efforts are focused on reducing long waiting times[27] in their public systems. Their healthcare systems have dealt with issues around controlling costs, improving the quality of care and the operational aspects of universal healthcare. Despite this success, they face pressures from elites and provider groups to increase the levels of public spending.

Thailand, on the other hand, has achieved universal coverage with such low levels of spending that it faces the design struggle of improving the quality of care that the universal program offers. Its investments in building the capacity of health policy agencies have helped develop and calibrate one of the most sophisticated payment systems among middle-income countries. The dominance of the Ministry of Public Health in the financing and delivery of the system has helped address resistance to universal coverage reforms, and thus the programme enjoys political support despite sustained periods of political instability and its political architect living in exile.

Vietnam and the Philippines continue to deal with most of the struggles mentioned above. Despite concerted policy efforts over the past 10 years, governments have been unable to make meaningful inroads to reduce OOP payments. Part of this stems from challenges in the design, particularly how healthcare providers are paid and, in part, the institutional inertia that fee for service payments enjoy, and a social insurance system that is poorly suited to realising universal coverage. Layered with this are operational challenges of enforcing existing regulations, holding errant providers accountable[28] and resistance from provider groups. Total health spending in both countries is relatively high, compared to its level of economic development. Importantly, most of this spending is mediated through the private sector via the OOP payments, reiterating the design struggle of universal health programs.

India and Indonesia’s universal coverage programmes, the most recent in the region, reflect learning from health reforms in the region over the past 20 years. Their design relies on sophisticated prospective payment instruments, have reasonable levels of political support, and coheres with existing health policy institutions. The struggle in these countries is more on committing resources to scale the program and addressing operational impediments. Current public spending, less than two per cent of GDP, offers limited instruments for the government to intervene in the sector and address its healthcare priorities.

Finally, there is the issue of trust in the health system. William Hsiao, a veteran observer of health reforms in low and low-middle income countries, has maintained that the ultimate litmus test of universal health coverage is if the ordinary person has trust in the public health system. That is, is the public health system easily accessible, does it provide quality care, and importantly does it inspire confidence among citizens? During the COVID-19 pandemic, in many countries in the region, the public health system was the first point of contact in accessing medical services – the first interface with a system that has been neglected, underfunded and resourced relatively to their private counterparts for decades. There is an urgent need to rebuild trust in the public health system among the citizens and ensure that it is not the last refuge of those who cannot access private healthcare.

There is a tendency in contemporary policy discourse to conceptualise impediments to achieving universal healthcare as primarily fiscal in nature, that is, governments just do not have the money to pay for universal healthcare. While this may be true in some instances, there is a range of other issues and challenges which public actors must navigate. Each of these struggles requires fundamentally different sets of policy capabilities, and policy debates should focus more on developing these specific capacities to manage them if we are to make meaningful progress in realising universal healthcare.

. . . . .

Mr Azad Singh Bali is an Associate Professor of Public Policy at the University of Melbourne’s School of Social and Political Sciences and an Honorary Associate Professor at the School of Politics and International Relations at Australian National University. He can be contacted at a.bali@unimelb.edu.au. The author bears full responsibility for the facts cited and opinions expressed in this paper.

[1] This is an edited version of the original article published by Melbourne Asia Review, Asia Institute, University of Melbourne.

[2] “The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2022”, United Nations, 7 July 2022, https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2022/

[3] “Out of Pocket Expenditure (% of current health expenditure)”, World Health Organisation Global Health Expenditure Database, 7 April 2023, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.XPD.OOPC.CH.ZS?locations=SG

[4] “The Impact of Out-of-Pocket Expenditures on Poverty and Inequalities in Use of Maternal and Child Health Services in Bangladesh”, Country Brief, Australian Aid and World Development Bank, December 2012, https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/30152/impact-out-pocket-spending-bangladesh.pdf

[5] “Out of Pocket Expenditure (% of current health expenditure)- China”, World Health Organisation Global Health Expenditure Database, 7 April 2023 https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.XPD.OOPC.CH.ZS?locations=CN

[6] “Out of Pocket Expenditure (% of current health expenditure) – Singapore”, World Health Organisation Global Health Expenditure Database, 7 April 2023, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.XPD.OOPC.CH.ZS?locations=SG

[7] “Out of Pocket Expenditure (% of current health expenditure) – Thailand”, World Health Organisation Global Health Expenditure Database, 7 April 2023, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.XPD.OOPC.CH.ZS?locations=TH

[8] Priyanka Sharma, “MMR dips from 130 to 97 per lakh live births between 2014-16 & 2018-20: MoS Health”, Mint, 14 December 2022, https://www.livemint.com/news/india/mmr-dips-from-130-to-97-per-lakh-live-births-between-2014-16-2018-20-mos-health-11671029557391.html.

[9] “WHO calls on countries to close gaps in health coverage for people affected by conflict and low-income households”, World Health Organisation News release, 12 December 2022, https://www.who.int/europe/news/item/12-12-2022-who-calls-on-countries-to-close-gaps-in-health-coverage-for-people-affected-by-conflict-and-low-income-households

[10] “Out of Pocket Expenditure (% of current health expenditure) – Singapore”, op. cit.

[11] Ibid.

[12] “About Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana (PM-JAY)”, Government of India National Health Authority, 2019, https://nha.gov.in/PM-JAY#:~:text=It%20covers%20up%20to%203,are%20covered%20from%20day%20one.

[13] Darmawan Prasetya and Eka Afrina, The Prakarsa Centre for Welfare Studies, Healthcare costs leave Indonesians out-of-pocket, East Asia Forum, 17 August 2022, https://www.eastasiaforum.org/2022/08/17/healthcare-costs-leave-indonesians-out-of-pocket/

[14] “From Double Shock to Double Recovery: Health Financing in a Time of Global Shocks”, The World Bank, 8 June 2023, https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/health/publication/from-double-shock-to-double-recovery-health-financing-in-the-time-of-covid-19

[15] “Drops in Health Spending Jeopardize Recovery from COVID-19 in Developing Countries”, The World Bank, Press Release, 21 September 2021, https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2021/09/21/without-significant-increases-a-full-sustained-health-and-economic-recovery-is-at-risk.

[16] Jishnu Das and Yamini Aiyar, “Will Ayushman Bharat Work?” Centre for Policy Research, Policy Engagements and Blogs, 21 September 2018, https://cprindia.org/will-ayushman-bharat-work/

[17] “Spending wisely: buying health services for the poor”, The World Bank Report, 15 May 2005, https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/845591468137396770/spending-wisely-buying-health-services-for-the-poor

[18] Siriwan Pitayarangsarit and Viroj Tangcharoensathien, “Sustaining capacity in health policy and systems research in Thailand”, Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 2009, https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/270376

[19] William C. Hsiao and R. Paul Shaw, “Social Health Insurance for Developing Nations”, The World Bank, 2007, https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/100/2012/09/hsiao_and_shaw_2007_-_shi_for_developing_nations.pdf

[20] Mukul Asher and Maurya Dayashankar “Financing of Health Insurance in India”, slide presentation, Universitas Indonesia, 8, October 2015, https://ash.harvard.edu/files/ash/files/appf_2015_slide_presentations_-_copy.pdf

[21] Azad Singh Bali, Alex Jingwei He, and M Ramesh, “Health policy and COVID-19: path dependency and trajectory”, Policy and Society, Volume 41, Issue 1, March 2022, https://academic.oup.com/policyandsociety/article/41/1/83/6515333

[22] Phil Galewitz, “Why hundreds of doctors are lobbying in Washington this week”, NPR, 17 February 2023, https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2023/02/17/1157926337/why-hundreds-of-doctors-are-lobbying-in-washington-this-week.

[23] Jiwei Qian, “Reallocating authority in the Chinese health system: an institutional perspective”, Journal of Asian Public Policy, Volume 8, 2015 – Issue 1, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/17516234.2014.1003454?journalCode=rapp20

[24] Mita Choudhury and Ranjan Kumar Mohanty, “Utilisation, Fund Flows and Public Financial Management under the National Health Mission: A Study of Selected States”, National Institute of Public Finance and Policy, India, August 2017, https://www.nipfp.org.in/media/medialibrary/2017/11/WHO_PFM_Report_Sep_2017.pdf

[25] “BPJS Kesehatan Claims Nearly 91% Indonesians Covered by JKN-KIS”, Tempo.co, 14 March 2023, https://en.tempo.co/read/1702469/bpjs-kesehatan-claims-nearly-91-indonesians-covered-by-jkn-kis

[26] Bibek Debroy, “Counting conundrum”, The Week, India, 13 September 2020, https://www.theweek.in/columns/bibek-debroy/2020/09/03/counting-conundrum.html

[27] “Median wait time for admission to hospital wards has gone up to 7.2 hours: MOH”, Channel News Asia, 25 April 2023, https://www.channelnewsasia.com/singapore/moh-hospital-waiting-times-7-hours-covid-19-3442136.

[28] Patricia B. Mirasol, “PhilHealth members still pay out of pocket in spite of universal healthcare:, BusinessWorld, 15 February 2023, https://www.bworldonline.com/health/2023/02/15/504818/philhealth-members-still-pay-out-of-pocket-in-spite-of-universal-healthcare/.

Pic Credit: Wikipedia Commons.

-

More From :

More From :

-

Tags :

Tags :

-

Download PDF

Download PDF