Summary

The Qosh Tepa Canal has the ‘potential’ of affecting water flow in Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan, and impacting agricultural production and related economic activities in the respective countries. Consequently, tensions over shared water and hydro projects may escalate in the region.

In its report on Afghanistan, the United Nations Development Programme observes that approximately 79 per cent of the country’s population does not have adequate access to water and 67 per cent of households are affected by drought-related hardships while floods impact an additional 16 per cent of the population. To deal with the severity of the water crisis, the Taliban regime has been engaged in building around 300 projects aimed at water management in different provinces. Some of these hydro projects create political issues with the neighbouring countries. For instance, in May 2023, the Iranian Border Guards and Taliban fighters clashed over water right on the transboundary Helmand River, resulting in three deaths.

Likewise, the Qosh Tepa Canal impacts Afghanistan’s ties with Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan. The canal was originally planned in the 1970s under the first Afghanistan President Mohammed Daud Khan (1973-1978). With help from the United States Agency for International Development, in 2018, President Ashraf Ghani (2014-2021) pursued the Qosh Tepa Canal project. In March 2022, under the Taliban, work began on the project. The second phase of the project started in 2024. The canal is 285 kilometres long, 100 metres wide and eight metres deep. It will have a capacity to carry around 650 cusecs (cubic metres per second) of water feeding the Balkh, Jawzan and Faryab provinces of Afghanistan. The canal is expected to extract 10 billion cubic metres of water from the Amu Darya River and aims to transform around 550,000 hectares of desert land into farmland in northern Afghanistan.

Historically, the first treaty over the Amu Darya River was the Treaty of Commerce and Navigation in 1843 between Britain and Russia. Agreements were subsequently signed in 1872, 1873, 1946 and 1958 between Afghanistan and Russia/former Soviet Union. Under the 1958 protocol, the two countries agreed to cooperate to “execute works for joint integrated utilisation of water resources” of the Amu Darya River.

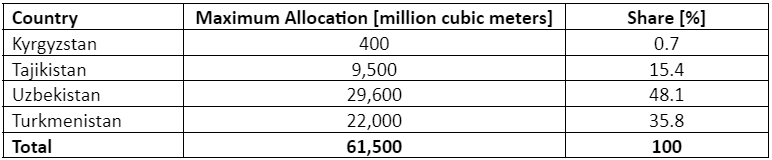

In 1977, after discussions in Tashkent, the Soviet Union offered six cubic kilometres of water in a year, three cubic kilometres short of the Afghan demand. Due to the difference, no agreement was signed. In 1987, after a series of meetings, Protocol 566, drafted by the Scientific and Technical Council of the then Soviet Union’s Ministry of Water Resources, was adopted by the four Soviet republics.

Table 1: Water Allocation Quota under Protocol 566

Source: Cited in Klemm, Walter and Sayed Sharif Shobair, ‘The Afghan Part of Amu Darya Basin: Impact of Irrigation in Northern Afghanistan on Water Use in the Amu Darya Basin’, https://unece.org/fileadmin/DAM/SPECA/documents/ecf/2010/FAO_report_e.pdf.

In February 1992, a few months after the Soviet Union collapsed, the newly independent Central Asian Republics (CARs) – Kazakhstan, Kyrgyz Republic, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan – entered into a new water management and utilisation agreement in Almaty. The agreement created the Interstate Commission for Water Coordination of Central Asia for the management of water allocation from shared rivers. As in the case earlier, Afghanistan is not a party to the Almaty agreement. In subsequent years, the CARs adopted several declarations and statements such as the Nukus Declaration (1995), the Ashgabat Declaration (1999), the Tashkent Statement (2001), the Dushanbe Declaration (2002) and the Joint Statement of the Heads of States – founders of the International Fund for Saving the Aral Sea (2009).

The Amu Darya Basin irrigates 2.3 million hectares of land in Uzbekistan, 1.7 million hectares in Turkmenistan, and drains around 0.5 million hectares in Tajikistan and 0.1 million hectares in Kyrgyzstan. Agricultural activities contribute to 17 per cent of Uzbekistan’s gross domestic product (GDP) and 10 per cent of Turkmenistan’s GDP. With the completion of the canal, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan could suffer a loss of up to 15 per cent of the current water flow from the Amu Darya River into their territories.

In 2023, Uzbekistan President Shavkat Mirziyoyev proposed “a joint working group to study all aspects of the construction of the Kushtepa (Qosh Tepa) canal and its impact on the water regime of the Amu Darya with the involvement of research institutes of [their] countries” and “involving representatives of Afghanistan into the regional dialogue on the sharing of water resources”. In March 2024, after a meeting between Uzbekistan’s delegation, led by Foreign Minister Bakhtiyor Saidov, with the Afghan officials, the Taliban reported that Tashkent had extended support for the Qosh Tepa Canal project. However, Uzbekistan did not comment on the matter then.

The Qosh Tepa Canal can escalate water tensions that may translate into political disputes between the Amu Darya River basin countries. However, some analysts, as Khudai Noor Nasar, believe that big projects involving the CARs and which traverse Kabul may make these CARs tread carefully on the canal matter. For instance, the Taliban has started work on TAPI (Turkmenistan, Afghanistan, Pakistan and India) gas pipeline project. Under TAPI, around 33 billion cubic metres of natural gas will be extracted from the Galkynysh gas field in southeast Turkmenistan and then pumped through a 1,800-kilometre pipeline traversing Afghanistan, including Herat and Kandahar in the south, before crossing into Balochistan province in Pakistan and ending in Fazilka in Punjab in India. Then, the 760-kilometre-long Pakistan-Uzbekistan railway service via Afghanistan connects Uzbekistan with Pakistani ports, capable of transporting up to 15 million tonnes of goods annually by 2030. It is scheduled to be completed by 2027. The railway link will decrease cargo delivery time between Uzbekistan and Pakistan by at least five days and slash the cost by 40 per cent.

Water stress and hydro projects, nevertheless, are likely to keep surfacing and will cause intermittent issues in the relations between Afghanistan and its Central Asian neighbours.

. . . . .

Dr Amit Ranjan is a Research Fellow at the Institute of South Asian Studies (ISAS), an autonomous research institute at the National University of Singapore (NUS). He can be contacted at isasar@nus.edu.sg. The author bears full responsibility for the facts cited and opinions expressed in this paper.

-

More From :

More From :

-

Tags :

Tags :

-

Download PDF

Download PDF