The India-US-China Triangle in South Asia:

Competition Drives Adaptation

Monish Tourangbam

14 November 2023Summary

Washington’s outlook towards South Asia deserves attention post United States’ (US) withdrawal from Afghanistan which sucked its strategic bandwidth and economic resources for two decades. One of the primary reasons for pulling out of the long-drawn-out war in Afghanistan was to devote the US’ resources and strategy to the more consequential competition with China in the Indo-Pacific. In this context, US priorities in continental and maritime South Asia need to be juxtaposed with the downward slide in India-China relations, the growing US-China rivalry and the burgeoning India-US strategic cooperation. The interaction among these three dyads produces a complex strategic triangle of cross-pollinating capabilities and intentions. The history of the India-US-China triangle and its contemporary evolution is a crucial indicator of the challenges and opportunities for peace and stability in South Asia.

Introduction

That South Asia, with both its land and maritime features, forms a significant sub-theatre of the Indo-Pacific region is apparent. While India remains the primary and predominant power in South Asia by dint of geography and history, the strategies of a proximate power like China and that of a distant power like the United States (US) are important vectors in regional geopolitics. Moreover, the way in which the smaller states of South Asia, whether in the Himalayas or the littoral states of the Indian Ocean, manage their ties with India, the US and China cannot be ignored either. With the shadow of the Indo-Pacific looming over the affairs of South Asia and India-China as well as US-China relations going downhill, growing strategic cooperation between India and the US is being seen with certain unease in Beijing, leading to a complex competition-cooperation-confrontation dynamic. The dilemma may be more pronounced for India, because in the triangular dynamics, India has a power asymmetry relative to China and the US. By exploring the intersection between these three dyads – India-US, India-China and US-China – in South Asia and their strategic implications, this paper attempts to make a case for greater India-US synergy to navigate the triangle towards regional peace and stability.

The India-US-China Triangle: Rewriting a Cold War Story

An overriding chapter in the script of 21st century geopolitics is the rise of China and its strategic ramifications across the world, and, more particularly, in the Indo-Pacific region. The competition-cooperation dynamic between India and China – two proximate neighbours – has caught the attention of analysts and policymakers, given its implications for the politics and economics of South Asia, which is a crucial sub-region of the Indo-Pacific. An aggressive and rising China, out to employ ingress into India’s territory and intent on increasing its strategic footprints among South Asian countries, makes it prudent for New Delhi to move closer to Washington. On the other hand, the emerging contours of US-China rivalry have led to New Delhi and Washington finding strategic convergences and working towards a strategic partnership.[1] China has remained a factor in South Asia’s power balance since its inception as a communist state in 1949; hence, becoming a major concern for the US’ containment strategy in Asia. How India viewed its relationship with China and vice versa bilaterally as well as potential partners in shaping the destiny of a post-colonial Asia was a vital story of the early Cold War years. At the end of World War II, the security and financial order that the US created was in a faceoff with its primary adversary, the communist bloc led by the Soviet Union. Therefore, a large Asian country like China going communist was deemed a big failure for US strategy and with the Soviet Union going nuclear in the same year plus reverses that the US later suffered in the Korean War, the threat from communism became a paranoia in US policymaking circles. There was apparent fear in the US government of newly independent countries in Asia, like India, turning towards communism, even as the Indian political leadership and the US diplomatic establishment in India tried easing such concerns.[2] The US government had set its sights on India as the most probable democratic counterweight to communist China and believed that ensuring India’s success, as a new nation-state, would prove a good example for democracy pitted against communism.

Following the Chinese takeover of Tibet, US espionage activities included training Tibetans and flying U2 flights from then Dacca to collect intelligence on Chinese nuclear developments. The impact of these developments on subcontinental geopolitics, including the fateful Sino-Indian war of 1962 is well documented.[3] As India’s initial perceptions of an Asian partner in China, turned bitter and proved misplaced culminating into the 1962 Sino-Indian war, New Delhi became more willing to explore a military partnership with Washington, despite propagating a non-aligned foreign policy. However, later in the decade, Washington prioritised exploiting the differences between China and the Soviet Union to its advantage by its outreach to China through Pakistan. The US-China rapprochement brought a significant turn in the history of the triangle, which brought the two erstwhile adversaries together against the Soviet Union. The Shanghai communique, also called the Joint Communiqué of the United States of America, and the People’s Republic of China (PRC), was signed during President Richard Nixon’s visit to China in 1972. The communique interestingly said, “Neither should seek hegemony in the Asia-Pacific region and each is opposed to efforts by any other country or group of countries to establish such hegemony… China will never be a superpower and it opposes hegemony and power politics of any kind.”[4] During the 1971 India-Pakistan war, the US clearly titled towards Pakistan which served as the conduit for the new US-China alliance. In such geopolitical circumstances, India signed a friendship and cooperation treaty with the Soviet Union.[5] The rise of the Deng Xiaoping era and the opening of China’s economy in the late 1970s gave birth to a new dimension in Beijing’s engagement with Washington. By the time the Cold War ended with the demise of the Soviet Union, the new dynamics of competition-cooperation in the India-US-China triangle were taking birth. Even as the US enjoyed a phase of unipolarity and unmatched influence in the international system, the discourse on the rise of new powers and a new order was already emerging.[6] Security as well as economic imperatives also provided an impetus in New Delhi and Washington to recalibrate a new phase of cooperation in their bilateral relationship.[7]

The 21st century brought forth new debates on the relative US decline, and the inevitability of an Asian century predicated on the simultaneous rise of India and China. The same period also coincided with the spectre of China’s rise entering threat calculations of the US national and foreign policy decision-makers, and hence recognising a favourable partner in India. New Delhi despite an economic narrative of cooperation and co-habitation with Beijing could not ignore the geopolitical threats emanating from proximity, history and competition in the South Asian sphere of influence. The wielding of the US power and its perception of adversaries, alliances and partners was entering a new era that was neither bipolar like that of the Cold War era nor a unipolar one, as new powers rose, with varying ways of dealing with the US.[8] As the Asia-Pacific resumed geopolitical significance and managing China’s rise became the primary test for the US foreign policy, India, with its own threat perceptions of China’s rise in its immediate neighbourhood, found convergence with the US.[9] Even as New Delhi and Washington found support at both ends, for their common concerns related to China and the need to jointly face this challenge, another reality permeates this triangular dynamics, which is interdependence with the Chinese economy.[10] The economic interdependence with China, both for New Delhi as well as Washington, is something that was absent before the rise of China as the most consequential trading nation in the 21st century. This interdependence created a new dynamic in the trilateral, raising questions about the extent to which these three countries navigate the imperatives of economics and the fallout of security dilemmas and arms race. Power asymmetry within the triangle drives the logic of deterrence, by beefing up one’s own capabilities or by building alliances and partners.

While geopolitical prudence informs China’s ambition to grow its deterrent capabilities vis-à-vis the US in the Asia-Pacific, and now the Indo-Pacific, India needs to enhance its deterrent capabilities particularly in its immediate neighbourhood, which includes continental South Asia and the Indian Ocean region. While the notion of the US’ extended deterrence adhered to a stricter obligation to protect its traditional allies during the Cold War, the emerging concept and practice of integrated deterrence involves a more comprehensive definition involving both “allies and partners”. The US National Defense Strategy of 2022 contended, “The Department will advance our Major Defense Partnership with India to enhance its ability to deter PRC aggression and ensure free and open access to the Indian Ocean region.”[11] The uneasiness in China’s policymaking and strategic community with the India-US bonhomie is discernible from a number of commentaries in publications such as Global Times. Many of these commentaries attempt to underline the differences between India and the US and call out the folly of the US’ containment strategy against China. They contend that the India-US cooperation, particularly in the military and defence sectors, could prove detrimental to regional security and hinder India-China relations. While the “US-India cooperation aimed at peace and development” was generally welcomed, they strongly condemned any bilateral “schemes targeting China” and emphasised that they, nevertheless, were not concerned because they knew “such schemes will not go far”.[12]

Navigating the India-US-China Triangle towards Regional Stability

The growing multipolar era has introduced new terms of engagement between the US and its adversaries or partners. Independent powers like India, while stitching a closer strategic partnership with the US, exude their own unique worldview and intend to practice their strategic autonomy. Just as Washington would like to preserve its own sense of competition-cooperation balance with Beijing, so does India, compatible with its own reading of national interest.[13] Geography clearly impacts this triangular interaction. India and China are two proximate powers, and, hence, China’s development and security partnership with India’s immediate neighbours influences India’s strategic thinking and operations. For a distant power like the US, the implications of China’s rise in South Asia are more relevant in the looming shadow of the broader Indo-Pacific construct.[14]

While the neighbourhood has always been prominent in India’s foreign policy calculations, it has now assumed a wider geopolitical significance, given China’s increasing economic and strategic interest in these countries, such as through the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). If the US is interested in counteracting China’s influence in South Asia, it should pay attention to South Asia’s response to China’s BRI. Even as Washington fails to match China’s investments in the region dollar by dollar, it, along with a partner like India, can provide alternatives. Such a proposition is also favourable to India’s interests, whose intention to provide public goods in South Asia may not be matched by its capability.[15]

One of India’s primary challenges in executing its foreign policy is to navigate its smaller neighbours’ ability to hedge their bets between India and China. While the case of the China-Pakistan alliance is starkly anti-India in its origin and evolution, other neighbours have displayed more complex balancing behaviours. India’s immediate neighbours negotiate their own border management, infrastructure investment, maritime governance and other forms of bilateral arrangements with Beijing.[16] How these small states pursue relations with both India and China, without necessarily falling into the strategic orbit of either, is a development that New Delhi requires to take cognisance of in its policy thinking and implementation.[17]

India has the twin challenge of dealing with two kinds of asymmetries – one with its neighbours that are materially weaker and another one with China, which has more capital to invest in India’s neighbourhood. While India’s smaller neighbours encounter an asymmetry vis-à-vis India’s geographical size and its political, cultural and economic influence, New Delhi also faces the challenge of dealing with the asymmetry that exists between its and China’s ability to provide material benefits to South Asian countries that desire both developmental aid as well as security assistance.[18] In addressing the asymmetry, that New Delhi faces vis-à-vis China’s growing means to influence perceptions and policies in South Asia, Washington’s ability and willingness to partner with India will be crucial. The notion of balancing as seen through hard-core arms race and strict alliances, and as seen during the US-Soviet Union Cold War, fails to capture the more complicated impact of the rise in China’s comprehensive national power.[19] A study at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace noted, “Due to India’s historical, political, and social connections with these countries, there seem to be limits to how deeply entrenched China can become. However, the balance is gradually shifting toward China, for the role it can play as a developmental partner as well as a balancing factor against the regional power, India. Moreover, India’s close presence in their social, political, and economic lives also leaves it open to heightened levels of criticism, including allegations of meddling.”[20]

At the same time, the smaller neighbours have a limitation against strictly forming an alliance with China. New Delhi and Washington should leverage this constraint among the neighbours to create traction to build its own influence in the region.[21] The changing balance of power in the Indo-Pacific and the growing great power rivalry between the US and China have brought this triangle into sharper focus. China’s intention and material capabilities to court and affect policy compliance in some of the critical geostrategic spots of South Asia, whether it is in the Himalayas or the Indian Ocean, puts it squarely at odds with both India and the US.[22]

Washington perceives China, as “the only competitor with both the intent to reshape the international order and, increasingly, the economic, diplomatic, military, and technological power to advance that objective” and resonates with New Delhi’s desire to prevent China’s unilateral designs in Asia.[23] China’s rising ambition in South Asia should be a concern to all those who care about a rules-based order in the Indo-Pacific. While smaller countries, in South Asia in need of development partners, might find it prudent to welcome Beijing’s overtures, India-US cooperation should adapt to the competition and challenges posed by China’s rise across the Indo-Pacific and in South Asia by creating alternative pathways of growth and development. India-US cooperation is reaching new heights beyond the bilateral, despite New Delhi remaining averse to strict alliances, which it perceives, is not in its interests and nor in the realm of its overall goal post in foreign policy.[24] On the other hand, many voices are calling out India for not investing enough in the India-US partnership. India, being the weakest, in terms of capability, in the triangle, has more complications and restraints in making its choices stark and seeks to derive strategic benefits out of its balancing act.[25] Moreover, other significant triangles involving one of the actors in the India-US-China triangle, at times, may interfere and interact with the strategic choices of these actors, forming what some call “strategic chains”.[26] For instance, how the India-China-Pakistan, India-China-Russia, India-US-Pakistan, India-US-Russia or the US-China-Russia triangles operate may impinge differently but substantially on how the India-US-China triangle evolves. Some, such as the India-China-Pakistan or the India-US-Pakistan equations, might have a distinct history and geography that is endemic to South Asia while others might have an extra-regional orientation to them. Nevertheless, these triangles, despite their different spheres of operations and influence, do require further exploration of their interactions.[27]

Amid these new dynamics in the India-US-China triangle and its interface with other permutations and combinations populating the Indo-Pacific region, it is imperative for New Delhi and Washington to explore new and critical areas of cooperation. One of them, calling for acute assessment and near-term implementation, given China’s inroads in the aspect, is that of connectivity and infrastructure projects in South Asia. The US needs to pay serious attention to the development gap in South Asia and work in concert with India which understands what the region needs, but may lack the material resources to build a feasible strategy.[28] The US Indo-Pacific strategy recognised India as a “like-minded partner and leader in South Asia and the Indian Ocean, active in and connected to Southeast Asia, a driving force of the Quad and other regional fora, and an engine for regional growth and development.”[29]

The Leaders’ Joint Statement of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad) between India, US, Japan and Australia in 2023 contended that the grouping “will continue cooperation with Indo-Pacific partners to meet the region’s infrastructure priorities. We will continue to support access to quality, sustainable and climate-resilient infrastructure investments in our region. We aim to ensure the investments we support are fit for purpose, demand-driven and responsive to countries’ needs, and do not impose unsustainable debt burdens”, the statement said. The Quad also announced “a new initiative to boost infrastructure expertise across the Indo-Pacific” named the ‘Quad Infrastructure Fellowships Program’ that “aims to empower more than 1,800 of the region’s infrastructure practitioners to design, build and manage quality infrastructure in their home countries”.[30] How to create incentives for its neighbours to appreciate its positive intervention in their economic and political affairs without overplaying its hand will remain a prominent foreign policy challenge for India. In economic terms, it would entail creating a web of relationships of economic interdependence between India and its neighbourhood. In political terms, it would mean creating space to build and maintain political convergences in these countries that are well disposed to work for regional growth and prosperity.

As India projects both the intention and capability to emerge as a leading power in the international system, how it manoeuvres its relationships with its immediate neighbours, which range from hostile to friendly, will be imperative. India will have to engineer its rise in a difficult neighbourhood, and that calls for diagnosing the inherent constraints accruing out of intra-subcontinental dynamics, as well as the involvement of extra-regional players. India’s ability to do so has been constrained by China’s increasing foray into South Asia recently, through economic incentives with strategic consequences. India’s strategy, in response, should be to build holistic partnerships with countries in the Indo-Pacific region that are equally concerned by China’s aggression with an aim to increase the cost for China to engage in activities that harm regional interests. Additionally, India can help facilitate alternative paths of growth for its immediate neighbours, by leveraging its partnership with the US and other like-minded countries, in ways that are transparent and mutually beneficial, as compared to China’s projects that are seen as debt-traps and one-way roads to Beijing’s domination. This will help reimagine a joint destiny of growth for India and its immediate neighbours, which will build more sustainable relationships and make them partners in India’s rise.

Conclusion

A dyadic understanding of the geopolitical and geo-economic environment in South Asia, either through an India-Pakistan or India-China lens, is incomplete. To understand regional dynamics, one of the critical triangles that merit study is the one between India, the US and China. The contemporary reality of this triangle is grounded in early Cold War history. Both capabilities and intentions play a significant role in shaping perceptions and misperceptions within the triangle. Specifically, India’s power asymmetry relative to that of China, and China’s power gap vis-à-vis the US drive each state’s regional posture. India’s bid to enhance its deterrent capabilities, with US assistance, is an eyesore to Beijing. Meanwhile, China’s growing military capabilities and defence modernisation as well as its increasing role as a development and security partner for a host of states in India’s immediate neighbourhood foment acute concerns in New Delhi and to a lesser extent in Washington.

The US-China dyad is clearly in a growing rivalry mode at the global scale and more prominently in the maritime belly of the Indo-Pacific. The crisis and confrontational mode is clearly manifested in geopolitical hotspots like the Taiwan Strait or the South China Sea. However, the Indian Ocean region as well as continental South Asia is clearly on the radar screen of China’s power projection and influence operations. The cooperative direction witnessed in the India-US dyad in the last two decades reflects their shared concerns about the China challenge, and it is imperative to translate this cooperative streak into communicated vision and implementation in South Asia, which is a consequential sub-theatre of the Indo-Pacific.

In South Asia, the US is a distant power in terms of geography but not as far as strategy and influence are concerned. While smaller South Asian countries seem to hedge their bets between India and China, the role of the US, with its growing rivalry with China in the Indo-Pacific, cannot be discounted. The US’ strategy in South Asia has largely focused on the triangular axis of India, Afghanistan and Pakistan but its Indo-Pacific strategy has been widening the menu of military and non-military engagements in the subcontinent. Shaping and reshaping relationships with its immediate neighbours, ranging from outright hostility to complex balancing like the ones seen in most of South Asia will be the test of India’s foreign policy toolkit. India has to navigate not only intra-subcontinental dynamics but also the involvement of extra-regional players that are either adversarial or friendly. Therefore, New Delhi’s handling of its immediate neighbourhood would require creating common grounds of vision and operation with like-minded stakeholders of a stable Indo-Pacific, particularly the US.

. . . . .

Dr Monish Tourangbam is a Strategic Analyst based in India and the Honorary Director of the Kalinga Institute of Indo-Pacific Studies. He is also a regular commentator on international affairs and India. He can be contacted at monish53@gmail.com. The author bears full responsibility for the facts cited and opinions expressed in this paper.

[1] Constantino Xavier, “Converting Convergence into Cooperation: The United States and India in South Asia”, Asia Policy 14, no.1 (2019), 19-50.

[2] Archival documents of the early Cold War era accessible through the Foreign Relations of the United States reflect such developments, https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments. Also see Tanvi Madan, Fateful Triangle: How China Shaped US-India Relations during the Cold War (Gurgaon: Penguin Random House India, 2020).

[3] Bruce Riedel, JFK’s Forgotten Crisis: Tibet, the CIA, and the Sino-Indian War (Noida: Harper Collins Publishers India, 2016).

[4] “Joint Statement Following Discussions With Leaders of the People’s Republic of China, Shanghai, 27 February 1972”, Foreign Relations of the United States, 1969–1976, Volume XVIII, Office of the Historian (US Department of State), https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1969-76v17/d203.

[5] Robert J McMahon, “The Dangers of Geopolitical Fantasies: Nixon, Kissinger and the South Asia Crisis of 1971”, in Nixon in the World: US Foreign Relations, 1969-1977, eds. Frederick Logevall and Andrew Preston, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008).

[6] Christopher Layne, “The Unipolar Illusion: Why New Great Powers Will Rise”, International Security 17, no. 4 (1993), 5-51.

[7] C Raja Mohan, Crossing the Rubicon: The Shaping of India’s New Foreign Policy (New Delhi: Viking India, 2003).

[8] Stephen M Walt, Taming US Power: The Global Response to US Primacy (New York: W W Norton & Company, 2005).

[9] R Nicholas Burns, “America’s Strategic Opportunity with India: The New US-India Partnership”, Foreign Affairs 86, no. 6 (2007), 131-146; Condoleezza Rice, “Campaign 2000: Promoting the National Interest”, Foreign Affairs 79, no.1 (2000), 45-62.

[10] Joseph S Nye, Jr, “Not Destined for War”, Project Syndicate, 2 October 2023, https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/us-china-not-destined-for-war-by-joseph-s-nye-2023-10

[11] “2022 National Defense Strategy of the United States of America”, US Department of Defense, https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/trecms/pdf/AD1183539.pdf; Anna Pederson and Michael Akopian, “Sharper: Integrated Deterrence”, Center for a New US Century, 11 January 2023, https://www.cnas.org/publications/commentary/sharper-integrated-deterrence

[12] Liu Xiaoxue, “US-India Relationship is Not As Rosy As It Seems on the Surface”, Global Times, 2 October 2023, https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202310/1299178.shtml; Liu Zongyi, “Will the US and India be Able to Work Together for Long?”, Global Times, 24 June 2023, https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202306/1293089.shtml?id=11; Global Times, “US Will Lose its ‘Huge Bets’ on China’s Neighboring Region: Global Times Editorial”, Global Times, 24 June 2023, https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202306/1293101.shtml; and Wan Hengyi , “US’ Plan to Rope in India to Serve Washington’s Purpose Wishful Thinking: Observer”, Global Times, 18 June 2023, https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202306/1292807.shtml.

[13] Monish Tourangbam, “The Future of US Power in Uncertain Times”, The Diplomat, 25 October 2023, https://thediplomat.com/2022/10/the-future-of-US-power-in-uncertain-times/; and Walter Russell Mead, “The Rules of Geopolitics Are Different in Asia”, Wall Street Journal, 2 September 2019, https://www.wsj.com/articles/the-rules-of-geopolitics-are-different-in-asia-11567460320.

[14] Monish Tourangbam and Vasu Sharma, “Where Does South Asia Fit Now in US Security and Defense Strategies?”, The Diplomat, 26 January 2023, https://thediplomat.com/2023/01/where-does-south-asia-fit-now-in-us-security-and-defense-strategies/.

[15] Manjari Chatterjee Miller, “China and the Belt and Road Initiative in India”, Council on Foreign Relations, June 2022, https://www.cfr.org/report/china-and-belt-and-road-initiative-south-asia.

[16] Kiran Sharma and Phuntsho Wangdi, “India Casts Wary Eye on Revived China-Bhutan Boundary Talks”, Nikkei Asia, 5 November 2023, https://asia.nikkei.com/Politics/International-relations/India-casts-wary-eye-on-revived-China-Bhutan-boundary-talks.

[17] T V Paul, “When Balance of Power Meets Globalization: China, India and the Small States of South Asia”, Politics 39, no. 1 (2019), 50-63; Darren J Lim and Rohan Mukherjee, “Hedging in South Asia: Balancing Economic and Security Interests amid Sino-Indian Competition”, International Relations of the Asia-Pacific 19, no. 3 (2019), 493-522.

[18] Monish Tourangbam, “Delhi’s Dilemma In The Neighbourhood: The Maldives’ Imbroglio”, India Times, 8 October 2023, https://www.indiatimes.com/explainers/news/delhis-dilemma-in-the-neighbourhood-the-maldives-imbroglio-617042.html.

[19] T V Paul, “When Balance of Power Meets Globalization: China, India and the Small States of South Asia”, op. cit.

[20] Deep Pal, “China’s Influence in South Asia: Vulnerabilities and Resilience in Four Countries”, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 31 October 2021, https://carnegieendowment.org/2021/10/13/china-s-influence-in-south-asia-vulnerabilities-and-resilience-in-four-countries-pub-85552. Also see Constantino Xavier & Jabin Jacob, eds., “ How China Engages South Asia: Themes, Partners and Tools”, Center for Social and Economic Progress, 3 May 2023, https://csep.org/reports/introduction-studying-chinas-themes-partners-and-tools-in-south-asia/.

[21] T V Paul, “When Balance of Power Meets Globalization: China, India and the Small States of South Asia”, 59, op. cit. Also see Rajesh Rajagopalan, “India’s Strategic Choices: China and the Balance of Power in Asia”, Carnegie India, 14 September 2017, https://carnegieindia.org/2017/09/14/india-s-strategic-choices-china-and-balance-of-power-in-asia-pub-73108.

[22] Mohan Malik, “Balancing Act: The China-India-US Triangle”, World Affairs 179, no.1 (2016), 46-57. Also see Tanvi Madan, “Major Power Rivalry in South Asia”, Discussion Paper Series on Managing Global Disorder no. 6, Council on Foreign Relations, October 2021, https://www.cfr.org/report/major-power-rivalry-south-asia

[23] “National Security Strategy”, The White House, October 2022, https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Biden-Harris-Administrations-National-Security-Strategy-10.2022.pdf, 8. Also see “Indo-Pacific Strategy of the United States” The White House, February 2022, https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/US-Indo-Pacific-Strategy.pdf .

[24] “Prime Minister’s Keynote Address at Shangri La Dialogue”, Ministry of External Affairs (India), 1 June 2018, https://www.mea.gov.in/Speeches-Statements.htm?dtl/29943/Prime+Ministers+Keynote+Address+at+Shangri+La+Dialogue+June+01+2018. Also see S Jaishankar, The India Way: Strategies for an Uncertain World (Noida: HarperCollins Publishers India, 2020).

[25] Ashley J Tellis, “America’s Bad Bet on India: New Delhi Won’t Side With Washington Against Beijing”, Foreign Affairs, 1 May 2023, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/india/americas-bad-bet-india-modi; Shivshankar Menon, “India’s Foreign Affairs Strategy”, Brookings Institution, 3 May 2020, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/indias-foreign-affairs-strategy/.

[26] Robert Einhorn and W P S Sidhu, “The Strategic Chain: Linking Pakistan, India, China, and the United States”, Arms Control and Non-Proliferation Series Paper 14, March 2017, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/acnpi_201703_strategic_chain.pdf.

[27] T V Paul & Erik Underwood, “Theorizing India–US–China strategic Triangle”, India Review 18, no. 4 (2019), 348-367.

[28] Deep Pal, “China’s Influence in South Asia: Vulnerabilities and Resilience in Four Countries”, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, op. cit.

[29] “The Indo-Pacific Strategy of the United States”, The White House, 16, op. cit.

[30] “Quad Leaders’ Joint Statement”, Ministry of External Affairs (India), 20 May 2023, https://www.mea.gov.in/bilateral-documents.htm?dtl/36571/Quad_Leaders_Joint_Statement. Also see Riya Sinha, “A Case for Greater US Focus on Infrastructure Development in South Asia”, Stimson Center, 17 July 2023, https://www.stimson.org/2023/a-case-for-greater-us-focus-on-infrastructure-development-in-south-asia/.

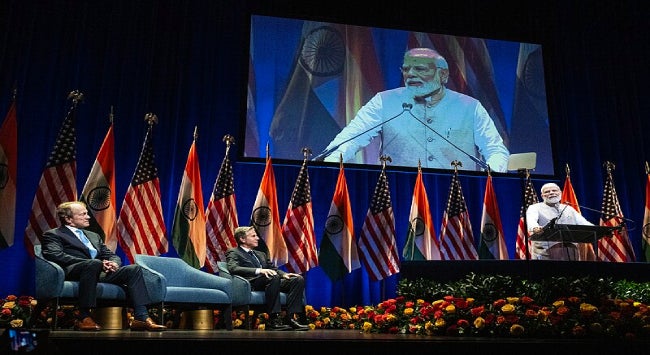

Pic Credit: Wikipedia Commons

-

More From :

More From :

-

Tags :

Tags :

-

Download PDF

Download PDF