Sri Lanka’s Port City Economic Commission Act: A Social-Legal Insight

R A Piyumani Panchali, Agana Gunawardana

16 July 2021Summary

The Port City in Colombo is a Special Economic Zone (SEZ) project launched in 2014 as a joint venture between the project company, CHEC Port City Colombo Pvt Ltd, and the Sri Lankan government. The law governing the Port City was passed with a simple majority on 20 May 2021 by the Sri Lankan parliament. This paper analyses the socio-legal implications arising out of the Act and aims to understand the impact of the Port City Act in fostering foreign direct investment in the SEZ.

Introduction

Establishing special economic zones (SEZs) is not out of the ordinary for states in the developing world. The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development defines SEZs as “geographically delimited areas within which governments facilitate industrial activity through fiscal and regulatory incentives and infrastructure support.” The term SEZ could include free trade zones (FTZs), which specifically involve infrastructure services exempted from taxes; export processing zones (EPZs) consisting businesses targeting foreign markets; as well as Industrial parks (IPs), which are designated for heavy industrial activities. With the objective of amplifying economic returns and reaching a high-income status, many developing states have adopted a services-led growth model at present. SEZ models are primarily three-fold: public SEZs; private SEZs and joint ventures. According to the Facility for Investment Climate Advisory Services (2008), the public SEZ model is thriving in China and Singapore due to their stable economies and efficient bureaucratic frameworks. Warr and Menon (2015) refer to the Phnom Penh SEZ in Cambodia as an example of a private SEZ model, which ensures direct economic returns to the private sector. The joint venture SEZ model found in Zambia and Nigeria has gained headway in many developing countries due to the public-private partnership fostered by the model.

Sri Lanka has housed several SEZs since the late 1970s, which includes EPZs and IPs. They provide businesses with investment incentives as well as tax and custom duties exemptions. These SEZs are owned by the Sri Lankan government and are administered by the Board of Investment (BOI). As such, SEZs are governed under the national regulatory framework and are integrated into the national economy sans blanket exemptions.

The Colombo Port City is a SEZ project launched in 2014 as a joint venture between the project company, CHEC Port City Colombo Pvt Ltd (CPCC), and the Sri Lankan government. This urban development venture spreads across 269 hectares of land reclaimed from the Indian ocean and aims at transforming the Sri Lankan economy to a services-led smart city in South Asia. The CPCC is a subsidiary of China Harbour Engineering Corporation (CHEC) and will lease 116 hectares of land for a period of 99 years, with the ability to sell the land to national or international investors. The Colombo Port City Economic Commission Act, No. 11 of 2021 (Port City Act), is the main legal framework governing the SEZ.

The Port City has been a controversial topic in the Sri Lankan landscape as well as in the international political economy. Since it is the only project in Sri Lanka that is officially mapped under the Belt and Road Initiative, the Chinese interest in the island nation as well as the region has been a point of contention for observers. The Port City project has also been subjected to various changes within the domestic socio-political climate of Sri Lanka. For example, pursuant to the regime change following the 2015 presidential election, the development of the Port City was suspended. Subsequently, the project area itself had to be increased from 233 to 269 hectares to compensate for the daily loss of US$380,000 (S$513,559) incurred by China during the suspension of the project.

Road to the Enactment of the Act

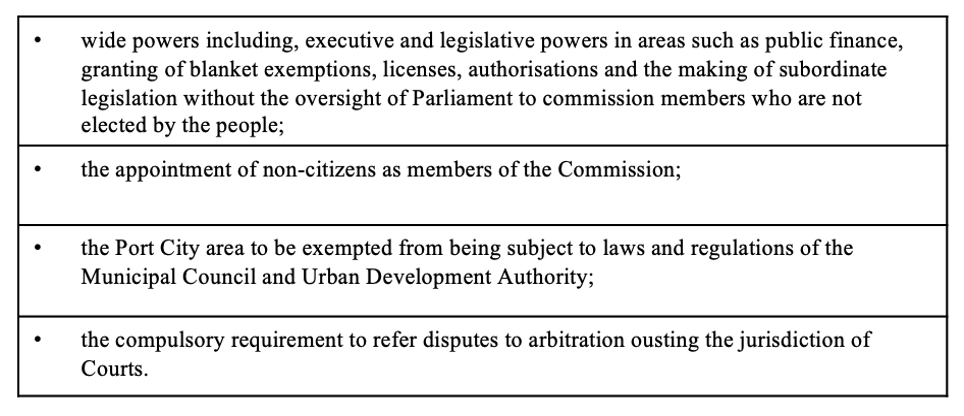

The Port City Bill was reviewed by the Supreme Court (SC) of Sri Lanka as 19 petitions were filed by various entities invoking the jurisdiction of the SC to determine whether the Bill is inconsistent with the Constitution of Sri Lanka. Conspicuously, the attention of the court was brought to the provisions in the Bill which enabled, (as claimed by the petitioners), inter alia:

Accordingly, the SC examined the clauses of the Bill, both individually as well as cumulatively. It was determined that the Bill is not unconstitutional and can be passed with a simple majority in the parliament, provided that several amendments (as proposed by the SC and at the Committee Stage) to the Bill are made.

It should be highlighted that the judicial review of the SC in determining the constitutionality of a Bill is limited to assessing whether the provisions of the proposed Bill fit within the four corners of the Constitution, and determining how the provisions of the Bill can be passed by the parliament. Thus, the SC’s Determination is not an assessment of the broader socio-economic and political impact of the Port City Act on Sri Lanka, as such power is only vested with the legislature of the state. The amended Bill was passed with a simple majority on 20 of May 2021 by the parliament and thus, became part of the Sri Lankan law.

Thus, it is crucial to note at this point, that any analysis on the legal framework of the Port City, henceforth, should be conducted by assessing the provisions of the Port City Act, as opposed to the Bill.

Introduction to the Port City Act

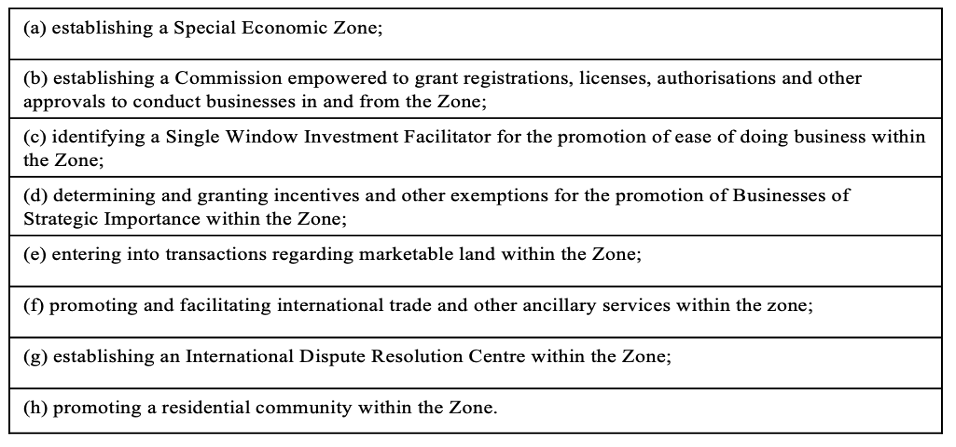

The Port City Act, as described in its long title, is enacted for several purposes, including:

The Act consists of the following parts:

The political discourse surrounding the enactment of the Port City Act thus far had a major focus on ‘passing the bill’. However, the Port City faces broader implications stemming from the multi-agency nature of the SEZ and the host government’s efficiency and ability to successfully coordinate as well as balance the interests of multifarious stakeholders. Hence, it is imperative to assess the socio-legal implications of the Act to Sri Lanka and underpin how the implementation of the Act could meets the expectations of a successful SEZ regulatory framework.

Criteria in Assessing the Socio-Legal Implications of a SEZ

In analysing the implications of a SEZ’s legal framework on a state, it is fundamental to identify the key stakeholders within the zone as well as their impact on the following three key interest areas:

i. Impact on shaping the business and investment environment within the SEZ;

ii. Impact on the scope of powers in monitoring and evaluating activities within the zone; and

iii. Impact on building a nexus between the SEZ and the domestic economy.

Stakeholders of a SEZ (such as regulator, owner, developer, manager and beneficiaries) are often fluid in terms of their functionality and scope of power depending on the model of the SEZ. In the joint venture model of the Port City, the SEZ involves stakeholders from both the host government as well as a private company. Depending on ‘who’s who’ and ‘who can do what’ within the project, the legal framework of the SEZ can result in both benefits as well as complex implications.

This paper analyses the extent to which the Port City Act empirically meets the aforementioned three-fold interests by observing the socio-legal implications arising out of the following selected provisions: Commission’s composition; Commission’s powers, duties and functions; exemptions provided by the Act; Commission’s accountability; and the dispute resolution mechanism. In doing so, the paper fulfils the objective of understanding the implications of the Port City Act in fostering foreign direct investment (FDI) in the SEZ.

Composition of the Commission

Section 2 of the Act establishes the Colombo Port City SEZ, and Section 3 establishes the Colombo Port City Economic Commission (Commission or Port City Commission). The Commission is a legal entity with perpetual succession and the power to contract under its name. In terms of Section 7, the Commission consists of five to seven members, the majority of whom, including the Chairperson (who has the casting vote), shall be citizens of Sri Lanka. The members are appointed by the President of Sri Lanka for a term period of three years unless a person vacates office by death, resignation or is removed by the President under the grounds specified in the Act. The members shall be eligible for re-appointment and a limit on such re-appointment is not stipulated in the Act.

When the Bill was first gazetted, there was no requirement that most of the members should be Sri Lankans which naturally became a point of contention. Even with the requirement now stipulated under the enacted Act, it still departs from the regular legal framework applicable to the rest of the country. For instance, the Urban Development Authority law requires the members of the Board of Management to be citizens of Sri Lanka. Although the departure from the regular framework in itself is not problematic and given the speciality attached to a SEZ, such departure may even be warranted, this particular departure essentially results in foreigners exercising control over policymaking in Sri Lanka.

On the one hand, since Sri Lanka already comes to the table with a lower bargaining power due to its economic and political status, there are clear implications of having a representative of a global or a regional ‘major power’ involved in the domestic policymaking process. On the other hand, there are concerns pertaining to the conflict of interest between the Commissioner’s role regarding the SEZ and the allegiance to the respective state of citizenship. For instance, if a Commissioner has interests aligning to India, China or the United States, depending on the foreign policy affairs of Sri Lanka at the time, there could be serious socio-legal implications on the Commission’s operational processes. This could result in Sri Lanka being stuck in complexities arising out of global and regional power struggles and move Sri Lanka away from an ‘equidistant’ foreign policy. In the worst-case scenario, the SEZ could end up as a proxy in the ongoing global and regional power struggles. Interestingly, the comparative legal frameworks of SEZs in the Philippines, Jordan, China and the United Arab Emirates do not have provisions enabling foreigners to serve in their respective regulating authority.

Thus, such irregularities of the Commission can result in a profound impact on the aforementioned interest areas. Whilst foreign expertise is crucial for a successful SEZ, such expertise could be brought in the form of advisory bodies as opposed to providing foreign citizens the ability to become a Commissioner.

Powers, Duties and Functions of the Commission

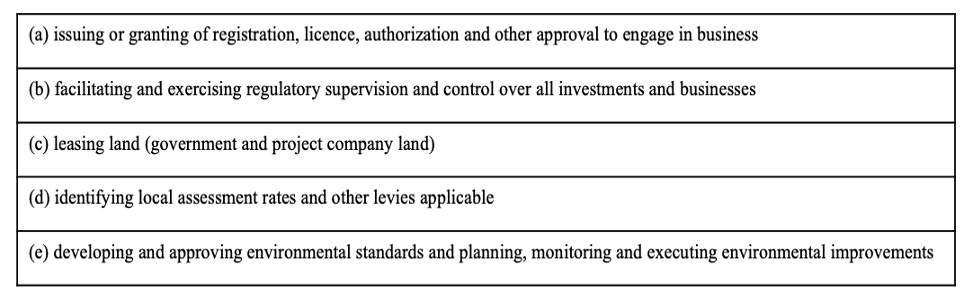

The Commission is entrusted with the “administration, regulation and control” of all matters, business or otherwise, “in and from” the Port City Area and is established to be the “Single Window Investment Facilitator” in Port City. As such, in terms of Section 6, the Commission is vested with several powers, duties and functions (in and from the Port City Area) including:

Furthermore, under Section 10(4), the Commission also has the power to make “Community Rules” for the owners and occupiers of condominiums or premises situated within the Port City Area to ensure a cohesive living environment. Therefore, overall, the Commission has been awarded a vast array of powers. However, there is much debate surrounding the repercussions of such granting of powers.

Although alarming at the outset, as demonstrated in the Philippines and Ghana, regulatory bodies with such comprehensive powers are not an anomaly in joint venture SEZs. An inherent feature of a SEZ is its ability to act as a one-stop shop for investors and thus, “the authority should have both business-like (management and operational functions, etc.) and government-like powers (where it assumes the role of a government agency or as a facilitator of public services).” However, it is noteworthy that the BOI, which administers the SEZs currently operating in Sri Lanka under the regular legal framework, has not been granted such broad powers as vested to the Commission by the Port City Act.

Powers in Relation to Regulatory Authorities

In the hope of furthering the Commission’s role as a Single Window Investment Facilitator, several statutory authorities such as the Municipal Council of Colombo, the UDA as well as the BOI have no applicability within the Port City area.

However, in certain circumstances, the Commission must act with the “concurrence” of ‘Regulatory Authorities’. A point of contention was raised before the SC regarding the scope of powers given to a Regulatory Authority in the Port City Area. It was argued that there could be room for arbitrary decision making, as the Commission decides the nature and scope of Regulatory Authorities’ powers.

The SC determined that the applicability of regulatory structure as set out in the Bill lacked clarity. Accordingly, several amendments were suggested to guarantee that the powers of the regulatory authorities are not ousted. These changes have now been incorporated into the Act so that the regulatory authorities can concurrently exercise powers with the Commission throughout the regulation process, which includes licensing/granting permission; supervision and monitoring; enforcement and punishment for violations.

It could be contended that enabling such concurrent jurisdiction could create bureaucratic red tapes for investors. However, through the amendments suggested by the SC, the Port City Bill was aligned with the constitutional framework of Sri Lanka. In any event, allowing a single body which possesses extensive government and business-like powers sans any checks and balances could result in arbitrary decision making which overlooks the whole point of creating a stable and sustainable business environment. Interestingly, the concurrent exercise of regulatory powers is not alien to the domestic legal framework in Sri Lanka, as the BOI exercises its powers concurrently with existing statutory authorities.

Powers in Relation to the Environment

In relation to SEZs, studies have remarked that services such as environment clearance could be facilitated by the regulatory authority of the SEZ. In the Port City, providing licences and any other environmental clearance rest with the Commission. This enables the Commission to fulfil its role as a Single Window Investment Facilitator, thereby providing investors one point of access to permits, licences and compliance with laws. However, a distinction should be made between providing “environmental clearance” and making “environmental standards”, as the former refers to the procedural aspect (licensing, authorisation, permits and certificates) and the latter refers to the substantive aspect of environmental governance including sustainable development.

The Commission’s power to set “environmental standards” could result in externalities stemming from the lack of technical know-how and resources. Moreover, even if the Port City functions as an SEZ, it shares the same ecosystem with Sri Lanka. In any event, environmental issues are of a transboundary character, and thus, the power of the Commission to determine such standards could have a profound impact on the present as well as future generations of Sri Lanka.

Thus, in exercising such powers, it is vital to ensure that there is inter-agency coordination between the Port City Commission and the Central Environmental Authority (CEA). For example, in the regular SEZ framework currently operating in Sri Lanka, a senior officer of the BOI is a member of the Environmental Council which is the advisory body of the CEA. Such inter-agency cooperation and coordination are underpinned to make sure that SEZs are not exempted from the national environmental protection laws. It is important to note that blanket exemptions in terms of environmental protection should not be provided within the Port City area at any given point, especially at the risk of causing irreparable damage to the ecosystem.

Exemptions for Businesses within the Port City Area

Part IX of the Act allows the Commission to determine and grant exemptions or incentives for the promotion of “Businesses of Strategic Importance”. Under Section 52(2), the Commission can determine which businesses can be designated as a “Business of Strategic Importance” in consultation with the President or the assigned minister (if any). Accordingly, in instances where a business is considered strategically important, it can be excluded from the purview of laws such as the Inland Revenue Act, No 24 of 2017, Value Added Tax Act, No 14 of 2002 and Foreign Exchange Act, No 12 of 2017, etc. Interestingly, exemptions can also be granted from the Termination of Employment of Workmen (Special Provisions) Act No 45 of 1971.

In addition, registered offshore companies and banks operating within the Port City Area are also exempted from the applicability of the regular domestic legal framework pertaining to offshore companies and banks established by the Companies Act No 07 of 2007 and the Banking Act No 30 of 1988, respectively. Thus, by permitting the Commission to make such exemptions, the Port City Act gives unprecedented investment incentives, in the hopes of unprecedented FDI inflow in return.

Deregulation with the intent of encouraging FDI is an inherent feature of SEZs, which could result in relaxed oversight and lack of transparency. Stemming from such deregulation, SEZs can be vulnerable to illicit activities such as money laundering. Being tagged as a haven for illicit activities, as opposed to an environment conducive for investment, could be a liability in attracting FDI, as legitimate businesses are driven away by such a negative reputation. This goes against the very purpose for which deregulation was introduced to the SEZ. Thus, due attention must be paid in maintaining the integrity and transparency in business activities within the SEZ.

For instance, in the mid-1990s, the FTZ in Aruba gained a negative reputation due to its vulnerabilities to illicit trade activities. It was discovered that the regulatory framework must be amended to ensure adequate control and transparency to market the integrity of the SEZ to attract legitimate businesses.

It is understood that the Act has bolstered the independence of the Commission by providing it with the flexibility to facilitate a framework which is conducive to an investment environment. Thus, it is important to ensure that blanket exemptions are not misunderstood as ‘incentives’, as the untarnished and exemplary image of the Port City as a whole is crucial to market itself as a destination for legitimate investments.

Implications on Accountability of the Commission

Given the Commission’s vast array of powers, it is useful to examine the provisions ensuring the accountability of the Commission. The Act provides for two points of assessment: submission of (a) an annual report; and (b) audit report to the President which is to be tabled before the parliament.

Under Section 15 of the Act, an annual audit must be conducted by a “qualified auditor” who may even be an international firm of accountants. At first glance, this marks a departure from the normal auditing framework applicable to other established commissions such as the Judicial Service Commission, Election Commission, Public Service Commission, Finance Commission, etc., where the Auditor-General conducts the auditing. However, Section 15 is subject to Article 154 of the constitution of Sri Lanka. Article 154(8) of the constitution defines the term “qualified auditor” as an individual or firm of accountants who possess/es a certificate to practice as an accountant issued by the Council of the Institute of Chartered Accountants of Sri Lanka, or of any other such legally established Institute.

Although the specification of an international auditing firm in the Act could be considered peculiar, it was observed that there are constitutional safeguards that are applicable to the procedure of appointment of “qualified auditor”. Further, the Act provides for both the audit report and annual report to be placed before the parliament. However, it is unclear as to whether such placing would result in a comprehensive oversight. “Accountability” is an important determinant which aids in the assessment of whether the SEZ realises the aforementioned three interest areas, particularly in building the nexus between the SEZ and the domestic economy. Thus, measures ensuring the Commission’s accountability should not be regarded lightly.

Resolution of Disputes in the Port City

Part XIII of the Act establishes the International Commercial Dispute Resolution Centre (ICDRC) offering alternative dispute resolution services, such as arbitration. In terms of Section 62(2) of the Act, any dispute arising within the Port City Area, either a) between the Commission and an authorised person or an employee of such authorized person; and b) the Commission and a resident or an occupier, should be resolved through arbitration conducted by the ICDRC. Further, Section 32 requires a clause stipulating mandatory arbitration to be included in any agreement entered into between the Commission and authorised persons. The SC has determined that the Act does not oust the jurisdiction of national courts from the Port City Area.

The option of providing alternative dispute resolution services is crucial in SEZs, particularly due to the inordinate delays and backlog of cases persisting in national courts. In a fast-moving commercial world, the traditional court system could be a hindrance in resolving disputes arising out of investments which require timely resolution.

However, the mandatory nature of the alternative dispute resolution mechanism specified in the Act could have implications as to the “appropriateness” of mandating parties to resort to the ICDRC as it goes against the fundamental concept of ‘party autonomy’ and ‘consensual dispute resolution’, the very concepts upon which arbitration as a dispute resolution mechanism is built.

Conclusion

In most instances, the legal framework in itself is not the cause of mischief, rather its administration and implementation. Deregulation to an extent is to be expected to realise the anticipated outcomes of a SEZ. However, history evinces that development at the cost of everything else is no development at all. As such, the world has moved on from an entirely ‘economic-centred’ development trajectory. States as well as private corporations around the globe focus on principles of sustainable development which include transparency, accountability and integrity as an integral part of their business ventures. Thus, neither the Port City Project nor the Commission can ignore these fundamental developmental principles. In fact, the Port City Act is at an interesting juncture. The administration and the implementation of the governing laws, considering the above-examined three-fold interests, will ultimately determine the success of the SEZ for all stakeholders (present and future) at play. Thus, just as much as the ‘rules of the game’ (legal framework of the Port City), the players of the game (stakeholders of the Port City) would undeniably determine the end result.

. . . . .

Ms R A Piyumani Panchali and Ms Agana Gunawardana are Attorneys-at-Law in Sri Lanka. Their views in this paper are personal and do not reflect the views of their employers. They can be contacted at piyumaniranasinghe@gmail.com and agana.gunawardana@gmail.com respectively. The authors bear full responsibility for the facts cited and opinions expressed in this paper.

Photo credit: Facebook/Port City Colombo

1 “World Investment Report”, UNCTAD, Geneva, 2019, p. 128, https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/wir2019_en.pdf. Accessed 15 June 2021.

2 FIAS, “Special Economic Zones: Performance, Lessons Learned, and Implications for Zone Development”, World Bank, Washington, 2008, pp. 2 and 29, https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/343901468330977533/pdf/458690WP0Box331s0April200801PUBLIC1.pdf. Accessed 15 June 2021.

3 P Warr and J Menon, Cambodia’s Special Economic Zones, Asian Development Bank, Manila, 2015, https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/175236/ewp-459.pdf. Accessed 16 June 2021

4 Lekki Free Trade Zone (Nigeria), Chambishi Multi-Facility Economic Zone (Zambia).

See M Mangal, Institutional Structure of Special Economic Zones (MYA-1903), International Growth Centre, 2019, https://www.theigc.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Mangal-2019-policy-paper.pdf. Accessed 18 June 2021.

5 A Sivananthiran, “Promoting decent work in export processing zones (EPZs) in Sri Lanka”, International Labour Organization, http://www.ilo.org/public/french/dialogue/download/epzsrilanka.pdf. Accessed 28 June 2021.

6 “Port City SEZ- A Catalyst for Modern Services in Sri Lanka”, Lakshman Kadirgamar Institute of International Relations and Strategic Studies, Colombo, 2020, https://lki.lk/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/2020R-Port-City-SEZ-22.05.20.pdf. Accessed 16 June 2021.

7 Anjelina Patrick, “Revival of Colombo Port City Project: Implications for India”, National Maritime Foundation, 27 October 2016, http://www.maritimeindia.org/View%20Profile/636131464409108056.pdf. Accessed 28 June 2021.

8 Bill titled “Colombo Port City Economic Commission” was published in the Government Gazette of the Republic of Sri Lanka on 19 March 2021 and was placed on the Order Paper of the Parliament on 8 April 2021.

9 Determination on the Colombo Port City Economic Commission Bill, S.C.S.D. Nos. 04/2021,05/2021,07/2021 to 23/2021, Available at https://www.colombotelegraph.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Determination.pdf. Accessed 14 June 2021.

10 Under Article 123(2) of the Constitution, if a Bill is determined to be unconstitutional, it should be passed by a) a two third majority in the parliament; or b) two third majority in the parliament and approved by people at a referendum, depending on which provisions of the Constitution that the Bill is inconsistent with.

11 Supra n.4 at p. 1.

12 Section 3(2) of the Act.

13 Section 6(1)(l) of the Act.

14 Section 10 of the Act stipulates that the quorum for a meeting shall be four members.

15 Section 8 of the Act.

16 Under Section 9(3) of the Act.

17 Section 4(2)(b) of the Urban Development Authority Law, No. 41 of 1978. See G Gunathilake, “Salvaging the Port City Project”, Daily Ft, 21 May 2021, https://www.ft.lk/columns/Salvaging-the-Port-City-Project/4-718186. Accessed 14 June 2021.

18 Philippines Economic Zone Authority, Aqaba Special Economic Zone Authority (Jordan), Administrative Bureau of Free Trade Zones (China), The Jebel Ali Special Economic Zone Authority (United Arab Emirates).

See “Bangladesh Special Economic Zone Framework: Key Issues”, World Bank Group, Washington, DC, 2012, http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/277651468205174255/Bangladesh-special-economic-zone-framework-key-issues. Accessed 17 June 2021.

19 Section 3(1) of the Act.

20 Boundaries of the area of authority of the Colombo Port City are demarcated in the First Schedule to the Act.

21 For instance, consider the Philippines Economic Zone Authority, The Industrial Estate Authority of Thailand and the Free Zones Board in Ghana. See supra n. 4.

22 Supra n. 18, p. 2.

23 See Section 73 of the Act.

24 “Regulatory Authority” as defined by Section 75 of the Act.

25 Determination on the Colombo Port City Economic Commission Bill, S.C.S.D. Nos. 04/2021,05/2021,07/2021 to 23/2021, p. 30.

26 For example, adding a new Section (Section 74) to the Act, expressly stating that the Act would not be deemed to restrict the powers, duties and functions vested in regulatory authority in the Port City area, unless otherwise expressly stated. Determination on the Colombo Port City Economic Commission Bill S.C.S.D. Nos. 04/2021,05/2021,07/2021 to 23/2021 at pp. 57-58.

27 Ibid., p. 30.

28 Supra n. 18, p. 2.

29 Section 7(1) (r) of the National Environmental Act, No. 47 of 1980.

30 Section 53(5) of the Act defines the term “Business of Strategic Importance”.

31 In terms of Section 52(3) of the Act, such businesses can be granted specific exemptions from enactments listed in the Second Schedule to the Act. See Second Schedule for the other enactments listed.

32 Section 41 of the Act excludes the application of Part XI of the Companies Act which specifically regulates offshore companies. Accordingly, provisions ensuring corporate governance principles such as transparency and accountability of companies stipulated in the Companies Act will not be applicable to offshore companies registered in the Port City Area.

33 Section 42 of the Act excludes the application of Part IV of the Banking Act which specifically provides for the oversight of such offshore banking businesses. Further, the supervisory powers over offshore banks which under the regular framework is vested in the Monetary Board, is given to the Commission under Section 49 of the Act.

34 FATF- GAFI, “Money Laundering Vulnerabilities of Free Trade Zone”, FATF/OECD, Paris, 2010, p. 16., https://www.fatf-gafi.org/media/fatf/documents/reports/ml%20vulnerabilities%20of%20free%20trade%20zones.pdf. Accessed 19 June 2021.

35 Ibid., pp. 38-39.

36 Article 154(8) of the 1978 Constitution of Sri Lanka.

37 Determination on the Colombo Port City Economic Commission Bill, S.C.S.D. Nos. 04/2021,05/2021,07/2021 to 23/2021, pp. 51-52.

-

More From :

More From :

-

Tags :

Tags :

-

Download PDF

Download PDF