Summary

Every four years, when Americans vote to elect their president, policymakers and analysts across the world keenly watch and follow the presidential election campaign and its outcome. Given the overwhelming influence of the United States (US) on global politics and economics, the result of the presidential election this November will have wide-‐ranging implications across all regions and countries in the world.

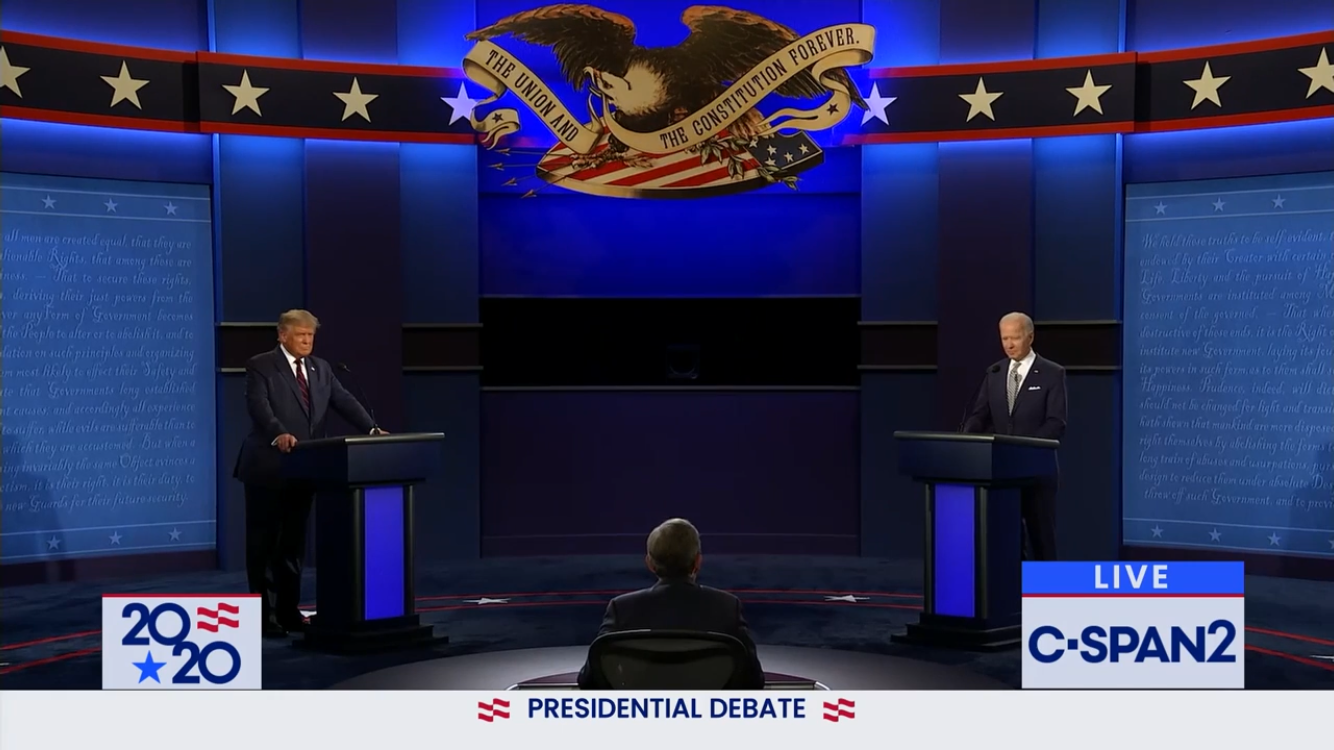

This paper assesses the impact of the 2020 US presidential election on South Asia. As the election campaign picks up heat in the coming days, the re-‐election campaign of President Donald Trump will highlight his achievements over the last four years and emphasise how ‘four more years of Trump’ will put ‘America First’. The presidential campaign of Joe Biden will attempt to show how the Trump presidency has negatively affected the domestic milieu and global image of the US and why American voters need to vote for a change of guard at the White House. In the context of the trends and patterns of Trump’s South Asia policy, this paper also analyses the changes and continuities that are likely to be seen in the US policy towards South Asia depending on the outcome of the 2020 presidential election.

Introduction

The presidential election in the United States (US) has always been a matter of public and policy discourse across the world. Even amidst debates relating to the relative decline of the country and the rise of other major powers, the US’ influence in global politics and economics remains overwhelming. The policies enacted in Washington and the strategies orchestrated in the American Beltway are keenly watched and studied across the world. Both foes and friends of the US recalibrate and reorient their foreign policies vis-‐à-‐vis the external manifestations of American policymaking. Therefore, the outcome of the US presidential election, as well as the rhetoric and reality of American politics, is of primary concern to policymakers and strategists across the world.

The US presidential election 2020 is extraordinary because of the circumstances in which it will be held. The election campaign is being carried out amidst the COVID-‐19 pandemic that has affected the political and socio-‐economic dynamics of the US. The election will either put President Donald Trump in the White House for four more years, or elect former Vice-‐ President Joe Biden as the 46th President of the US. Irrespective of who comes to power in November 2020, the political leadership and bureaucracies of countries around the world will have to keep their feet on the fire to deal with the consequences.

Like any other geopolitical region in the world, the 2020 US presidential election will have a profound impact on South Asia, specifically on India, Pakistan and Afghanistan, which are No. 645 – 7 October 2020 6 the navigating pivots of US strategy in the region. This paper will analyse what four more years of Trump or a new Biden presidency could mean for the US policy priorities in the region, and what could be the continuities and the changes are likely to be.

South Asia in the Trump Administration’s Foreign Policy

In November 2016, Trump, a maverick American businessman, to the surprise of many in America and around the world, won the US presidential election and became the 45th American President. When Trump, who was hardly taken seriously as a contender for the top job in America, went on to win the election, policymaking elites around the world had to reorient their immediate responses and longer-‐term strategies. When he assumed the presidency, where did the three most important vectors of Washington’s South Asia policy – the Afghanistan war; ties with Pakistan; and strategic partnership with India – stand?

Even before Trump made public his South Asia policy in the fall of 2017, America’s long war in Afghanistan was far from over, and it was becoming starkly clear that militarily defeating the Taliban was no longer the objective.1 The Taliban was clearly negotiating from a position of strength and was going to feature some way or the other, in the future polity of Afghanistan. The US was exiting Afghanistan, and it was only a matter of specifics as to how it was going to do so. Despite Pakistan’s continuing relevance in Afghanistan, the US-‐ Pakistan relationship had faultlines. While the US expected Pakistan to do more to fight terrorism, Pakistan complained that its sacrifices and efforts in the global war on terror were not being well appreciated in Washington. Trump and his national security team had emitted enough signals that they intended to pull the reins harder on Pakistan, asking tougher questions on the latter’s commitment to countering terrorism and applying more conditions on US aid to Pakistan. Meanwhile, America’s strategic convergence with India to counteract the rise of China in the Indo-‐Pacific, particularly in the realm of defence cooperation, was lending it a new meaning and direction. Moreover, the US seemed to be much more welcoming and appreciative of India’s contribution to the reconstruction efforts in Afghanistan. Irrespective of the uncertainty attached to Trump’s presidential style, the foundation of the India-‐US strategic partnership largely remained firm.

One of Trump’s election campaigns that echoed outside and inside the US was his call to put ‘America First’ in his domestic and foreign policy. Did it mean an American retreat from world affairs as many debated? Did it mean a more transactional America? The disruptions that the Trump presidency brought in has been consequentially felt in American domestic politics and its foreign relations with its traditional transatlantic and transpacific alliance partners. In comparison, the US’ strategy in South Asia under Trump’s presidency saw more continuity than change.2 South Asia also remained a critical node in Trump’s Indo-‐Pacific strategy, given the centrality of America’s relationship with India in the same, and the management of China’s rise. A number of American strategic documents have categorised the strategic competition with China as its priority, and in the same geopolitical context, the convergence with a country like India has featured prominently.3 America’s engagements with the outside world have often swung between support for interventionism and isolationism. Debates on the US’ relative decline and China’s unmistakable rise have only accentuated this trend.

Scepticism towards engulfing America into the vortex of regional problems, and prodding countries to take bigger responsibilities toward solving problems in their neighbourhood has been the developing trend that was carried over from the Barack Obama to the Trump presidency. Perhaps the tone and tenor in which President Trump communicated it to allies, partners and the international community with his ‘America First’ call was different from the more nuanced and persuasive diplomatic style of his predecessor. To end foreign wars and bring American troops back home has been an enduring campaign slogan for the US presidential election and both candidates will campaign to end the two decades old military campaign in Afghanistan. As far as US policy in Afghanistan is concerned, the dice has been rolled with the signing of the US-‐Taliban peace agreement.4 It remains to be seen how another four years of President Trump or a change of guard at the White House will see through the tense days ahead for the peace negotiations in Afghanistan involving the Taliban and the representatives of the Afghan government and the nature of US engagement in the country post withdrawal.

Trump’s earlier projections to play hardball with Pakistan sobered later, with Pakistan playing its card in America’s increasing eagerness to exit from Afghanistan through a peace deal that has led to the more treacherous path of intra-‐Afghan peace talks. The leverage of America’s power in its dealings with Pakistan and its ability to extract what it wants from Pakistan has always been filled with ambiguity.5 Trump’s meeting with Prime Minister Imran Khan in Washington last year came out more like an effort at inflating Pakistan’s stature and role in South Asia. Lately, Trump has toyed publicly with the proposition of mediating peace between India and Pakistan, something Delhi has repeatedly objected to. Trump is not the first and will not be the last US president whose intentions to put the pedal on Pakistan’s dubious counter-‐terrorism efforts will be questioned in Delhi. Extricating from its difficult dalliance with Pakistan was always going to be a difficult proposition for any administration in Washington and the ensuing peace talks in Afghanistan will mean continuing to deal with Pakistan even in the face of diminishing returns.6

US-‐China Relations: Implications for South Asia

The pandemic has clearly hastened the ensuing great power competition between the US and China, and in such a scenario, what will a recalibration of US foreign policy look like? There are a number of uncertainties and countries across the world, particularly the ones in the Indo-‐Pacific region, will be watching Washington’s overtures and calculating the operational cost of protecting and promoting their own national interests in the same milieu.7 How the next administration in Washington deals with its China challenge will have deep implications for South Asian geopolitics? The question of the 2020 US election and its implications for South Asia is deeply intertwined with the trajectory of the US-‐China relationship. More than what the presidential contenders think and say about South Asian countries, it is rather what Biden and Trump say about China that might be more intensely watched.

The geopolitical trend of the rise of China, to which Trump’s predecessor, President Obama, responded through the Asia rebalancing strategy, has intensified during Trump’s presidency through the Indo-‐Pacific strategy. The US-‐China geopolitical tension is likely to broaden and deepen regardless of who wins the election. With India-‐China relations going south in the midst of the intense border crisis at the Line of Actual Control and China’s growing influence in the South Asian region, how the US deals with China unilaterally and in concert with other powers will be of major consequence for South Asia. The challenge of managing the strategic repercussions of China’s Belt and Road Initiative will remain a prominent feature of US foreign policy and of countries like India. In addition, how the next administration deals with countries like Russia and Iran that have been at the receiving end of the Countering America’s Adversaries through Sanctions Act, will have at the least a tangential impact on South Asian countries, particularly on how India, Pakistan and Afghanistan deal with these countries in the near future.

Foreign Policy Speculations for a Biden Presidency

The Trump administration has often been criticised for its lack of dependence on the traditional corridors of US diplomacy. Therefore, a Biden-‐Kamala Harris team at the White House is likely to bring back a State Department-‐oriented diplomacy led by career officials and political appointees at various levels of the diplomatic ladder, particularly on posts related to regional management of American foreign policy strategy and implementation. Writing for Foreign Affairs, Biden contended, “As president, I will elevate diplomacy as the US’ principal tool of foreign policy. I will reinvest in the diplomatic corps, which this administration has hollowed out, and put US diplomacy back in the hands of genuine professionals.”8

As far as economic ties are concerned, the extent of America’s commercial and trade relations with India stands out among the South Asian countries. However, Trump’s focus on tariff reciprocity and obsession with balance of trade rather than a strategic view of economic ties has led to some negative trends.9 While the Trump administration was boasting of improvement in the US economy, the pandemic has severely affected it and, hence, whether a change of administration will reverse the protectionist streak in US economic diplomacy remains to be seen. Whether a Biden administration will move the economic ties with India to a more strategic direction will be an important development to watch. Another area where a Biden administration is likely to bring changes is it dealing with the issue of climate change, which might see a return to the Obama era focus on clean energy research and collaboration with other countries, including in South Asia.

The issue of immigration might see substantial change particularly in the case of a Biden presidency. Biden’s ‘agenda for the Indian American community’ contends that “he will support first reforming the temporary visa system for high-‐skill, specialty jobs to protect wages and workers, then expanding the number of visas offered and eliminating the limits on employment-‐based green cards by country, which have kept so many Indian families in waiting for too long.”10 However, much will depend on how the American economy, hit hard by the pandemic, rebounds, allowing for a domestic political and socio-‐economic environment conducive to job seeking immigrants coming to the US. The nomination of Senator Harris, who has Indian roots, as the vice-‐presidential candidate for the Democratic Party, has led to much public debates in India, irrespective of the real political outcomes of her candidature. The Democratic Party released digital graphics in 14 Indian languages to cater to the Indian-‐American electorate, who largely populate some of the key battleground states in the US. The Trump campaign launched four new coalitions – ‘Indian Voices for Trump’, ‘Hindu Voices for Trump’, ‘Sikhs for Trump’ and ‘Muslim Voices for Trump’. Both the parties also seem to be taking cognisance of the Indian-‐American community for its fundraising ability. Trump’s efforts to reach out this community were clearly visible during the ‘Howdy Modi’ event last year and the ‘Namaste Trump’ event early this year.11

Conclusion

For all regions and countries across the world, the US presidential election is a time to debate and discuss the ways in which Washington reshapes and recalibrates its strategies and foreign policy approaches. South Asia will continue to feature prominently in the form of how the new administration deals with the endgame in Afghanistan and how it deals with its China challenge in the broader Indo-‐Pacific, in which maritime and continental South Asia features prominently.

A general argument pervades that foreign policy issues do not matter much in determining the voting patterns of Americans. However, the process and outcome of the US presidential election does reflect America’s own sense of standing in the world, and affects how the world views the fate of America’s future. Therefore, what transpires in the internal and external dynamics of the US has a bearing on the geopolitics of all regions, including in South Asia.

. . . . .

Dr Monish Tourangbam is a Senior Assistant Professor at the Department of Geopolitics and International Relations, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal, India. He can be contacted at monish.t@manipal.edu. The author bears full responsibility for the facts cited and opinions expressed in this paper.

Photo credit: AP/Getty/Reuters

-

More From :

More From :

-

Tags :

Tags :

-

Download PDF

Download PDF