Summary

The recent assassination of former Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has left the world in shock. Abe was a consequential leader for the world and India-Japan relations. World leaders poured words of praise and recounted Abe’s sterling contribution to the international stage while condemning the violent attack, prematurely ending his life. India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi issued several tweet messages, calling Abe his close friend and saying that “he was not only my but also India’s trusted friend”. He wrote an obituary titled ‘My friend, Abe-san’, outlining his cherished memories of Abe. In Abe’s demise, India lost a great friend and great champion.

Introduction

The world is in shock and mourning the assassination of former Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe on 8 July 2022. Abe was campaigning for the upper house elections in Nara, western Japan, supporting a ruling party candidate when he was shot. This will most definitely be recorded as a dark day in Japan’s history – a society with extremely low crime rates and stringent gun laws. Political violence in Japan is rare in post-war Japan. The killing of such a high-profile political figure, Japan’s longest-serving prime minister, was, until now, unthinkable. This is now Japan’s ‘JFK moment’.

The untimely death of Abe, aged 67, is not only a huge loss to Japan but also to the world. Abe was a transformational leader in global politics. He raised Japan on a higher pedestal internationally through his strategic vision and initiatives. Even during his retirement, Abe worked tirelessly for his Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) and actively campaigned during national elections, especially in support of young and emerging leaders.

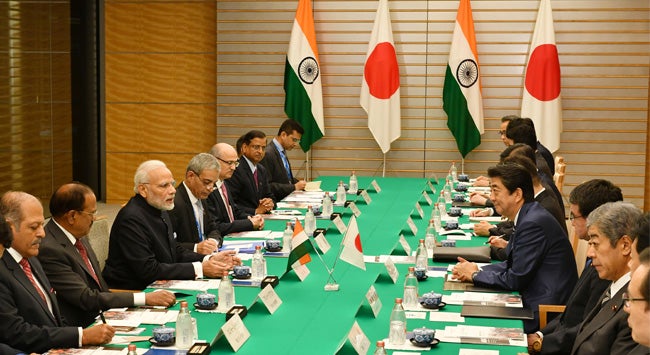

While Abe’s global contribution is remarkable, for Abe, India was special, and his chemistry with Prime Minister Narendra Modi was solid. No other Japanese prime minister has ever been as India-inclined as Abe, and his contributions to Japan’s India engagement will remain unparalleled. While it will be challenging to fill Abe’s shoes, Japan will need to do much soul-searching and keep the strategic momentum that Abe built going.

Abe’s Political Background

Abe came from a well-known political family from Japan’s Yamaguchi prefecture, located in the western part of Japan’s main island. His maternal grandfather, Nobusuke Kishi, was Japan’s prime minister in the 1950s. Kishi was Japan’s first post-war leader to visit India in 1958. Although Abe’s paternal grandfather, Kan Abe, also served as a parliamentarian, the younger Abe was deeply influenced by Kishi’s conservatism and his focus beyond the United States (US) and Europe on the Asia-Pacific, including India. Abe’s father, Shintaro Abe, was also a politician who served for more than three decades in public life, including as minister of foreign affairs. The Abe family is well-known in political circles in Tokyo. As Abe did not have a child of his own, one of his principal interests was to mentor emerging Japanese leaders.

Abe inherited the electoral district of his father in Yamaguchi – their native prefecture – a couple of years after the latter’s death in 1991, and was elected to the Lower House in 1993 and won every election since then. After serving in many ministerial and party posts, Abe was finally elected Japan’s prime minister in 2006, following Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi. However, Abe did not last long in this role and stepped down in September 2007, citing health issues, soon after his very successful visit to India in August 2007. Abe stepping down as prime minister had less to do with his health and more with LDP pressure because of his party’s poor performance in the 2007 Upper House elections.

After five years of political turmoil in Japan, with prime ministers from both the LDP and opposition Democratic Party of Japan rotating annually, Abe made a remarkable comeback as prime minister in 2012 and served in office until 2020. He was Japan’s longest-serving prime minister since the late 19th century. Abe suddenly resigned in late 2020, citing ill-health again as he had done in 2007. Although never proven, at the time, there were a number of political scandals surrounding him and his wife, with allegations of violating elections and public funds laws.[1][2]

Post-prime ministership, Abe remained actively engaged in the LDP’s affairs as the head of the party’s largest faction. It is not an exaggeration to say that Abe was an LDP ‘king-maker’, greatly influencing the selection of his successors – Yoshihide Suga and Fumio Kishida. His death has left a massive void in the party, in Japanese politics generally and in Japan’s global engagement.

Abe in Global Politics

Japanese prime ministers are not known for their global leadership, but Abe was an exception. Given the tributes flowing in from world leaders, it is not hard to appreciate how much respect he commanded internationally.

World leaders, including United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres and Queen Elizabeth II, poured words of praise and recounted Abe’s sterling contribution to the international stage while condemning the violent attack on him.[3] In a rare joint statement issued by the leaders of the four Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (also called the Quad) nations, they declared that “We will honour Prime Minister Abe’s memory by redoubling our work towards a peaceful and prosperous region”.[4]

One of Abe’s most outstanding contributions to international relations was his vision of a ‘free and open Indo-Pacific’. He pushed for a connection between the Indian and Pacific Oceans nations into a single strategic frame, turning away from the older Asia-Pacific concept because countries like India and many of the nations of East Africa were excluded. His diplomacy was so robust that he was even able to sell this concept to US President Donald Trump and many leaders worldwide, including those in Europe who were neither Pacific nor Indian Ocean states.

Another of Abe’s ideas was to bring democratic nations together in a grouping that he had once called “Asia’s democratic security diamond” where Japan, as one of the oldest sea-faring nations, should play a greater maritime role, alongside India, Australia, and the US in preserving stability in both the Indian and Pacific Ocean regions.[5] He made this proposal soon after returning to power in 2012, later becoming the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue or Quad 2.0.

It was due to Abe’s hard work and his deep interest in Japan playing a leading strategic role in the Indo-Pacific that the Quad was not only resurrected but also elevated from the official and ministerial levels to a leaders’ level summit, the latest of which was held in Tokyo in April 2022.[6]

When Trump withdrew from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) in 2017, some leaders thought the TPP was ‘dead in the water’. Abe rallied forces and convinced the other partners to go ahead with it even without the US. As one commentator noted, “Against all odds, Abe rallied the 10 other TPP member countries and ultimately won their support for a Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP} that largely kept the previous agreement intact and left the door open to an eventual US return.”[7]

As part of an ambitious reorganisation of Japanese foreign and security policy, Abe established the National Strategic Council in 2013 and issued Japan’s first National Security Strategy. The aim was to centralise security and foreign policy-making as a whole government approach, breaking the tradition of the sectional interests of various ministries and bureaucracies across government. Abe successfully made critical changes in Japan’s defence policy through legislation without amending the constitution.

Abe also made profound changes to the structure of Japan’s foreign policy-making. He controversially broke many past taboos such as collective self-defence, paving the path for Japan to provide military support to its ally, the US, and other states in a variety of contingencies. The changes introduced by Abe to Japan’s domestic policy and the country’s global initiatives will remain his legacy for decades to come.

Abe’s Unfinished Tasks

Two tasks that Abe had set for himself remain unfinished. First, he wanted to secure a peace treaty with Russia by solving a long-standing territorial dispute since the end of World War II. Second, he sought to amend Japan’s post-war constitution for the first time, in particular Article IX, which restricts Japan’s military activities.

Abe held more than two dozen meetings with Russia’s President Vladimir Putin, including high-level meetings between senior ministers and officials of both countries. As late as September 2019, it seemed that an agreement might be reached and a peace treaty signed.[8] However, in the end, this hope fell apart.

Abe’s second mission was to change the constitution. He began to work on it when he first became prime minister in 2006. After his return to office in 2012, he focused more on this project, but this did not eventuate for several reasons, mainly because there was a lack of consensus within the ruling coalition. Abe was uncertain whether the proposal would go through the required public referendum. Even in his retirement, Abe did not disengage himself from this mission, and he was pushing the envelope as hard as possible in the hope that it would happen soon.[9]

Abe and India

A critical contribution of Abe was his elevation of India’s position as Japan’s national foreign policy priority. Although this momentum was started by his predecessors Yoshiro Mori and Junichiro Koizumi through their visits in 2000 and 2005, respectively, Abe made India a central plank of Japan’s foreign policy.

What was remarkable about Abe was that he was the first Japanese leader who identified India as a key future partner even before he became prime minister. In his book, Utsukushii kuni e, published in 2006, Abe highlighted India’s importance and speculated that Japan-India relations may surpass Japan’s relations with the US and China in 10 years. As the grandson of Kishi, who had visited India in 1957, Abe understood India well through his grandfather’s assessment of India and the country’s potential. Even before he became prime minister, Abe had visited India as Japan’s Chief Cabinet Secretary and met with India’s then Prime Minister, Manmohan Singh.

However, a real breakthrough in the relationship came when Abe visited India in August 2007 and presented his speech entitled the ‘Confluence of the Two Seas’ to the Indian parliament. During his speech, Abe said that Japan had “rediscovered India as a partner that shares the same values and interests and also as a friend that will work alongside us to enrich the seas of freedom and prosperity, which will be open and transparent to all.”[10] Abe’s visionary idea of the co-mingling of the Pacific and the Indian Oceans finally developed into Abe’s signature policy of a ‘Free and Open Indo-Pacific’ strategy/vision, embraced today widely across many continents. Abe’s 2007 speech in India underlined the changing perception of India within Japan’s elite circles. Since that speech, Japan-India relations have gone from strength to strength.

When Abe returned to power in 2012, his enthusiasm for India increased. His Indian counterpart, Singh, invited Abe as the chief guest at India’s Republic Day parade in 2014, becoming the first Japanese prime minister to receive this invitation. With Modi as prime minister in India from 2014 onwards, the Abe-Modi bromance flourished like never before.

Abe offered some very special gifts to India by persuading Japan’s aid agency – Japan International Cooperation Agency – to provide unprecedented loans on exceptionally generous terms. This proved critical for India’s first high-speed train based on Japan’s bullet train technology. Never has Japan offered such a large loan (over US$10 billion) [S$14 billion] for a single project, not even to China, where the bulk of Japan’s official development assistance flowed in the 1980s and 1990s.

Abe not only lifted the bilateral relationship to new heights, but he was also the force behind bringing India into several minilateral frameworks such as the Quad and the trilaterals, for example, Japan, India and the US. Under Abe, Japan-India relations expanded in multiple fields, including economic, diplomatic and, most notably, in defence and security. High-level exchanges involving defence personnel became more frequent.[11]

Abe has left an enduring and lasting mark in developing a comprehensive partnership with India. Even after retiring from the prime ministership, Abe continued to bat for India. Only recently, he took up the position of Chairman of the Japan-India Association, the oldest association promoting bilateral relations for more than a century.[12] In an interview as late as May 2022, Abe said that the “India-Japan relationship has the biggest potential”.[13] In recognition of his extraordinary contribution to developing and solidifying Japan’s relations with India, the Indian government awarded Abe with India’s second-highest civilian award – the Padma Vibhushan.

On Abe’s tragic and premature end of life, Modi issued several tweet messages. He called Abe his close friend and said, “he was not only my but also India’s trusted friend”. Modi further noted that “Mr Abe made an immense contribution to elevating India-Japan relations to the level of a Special Strategic and Global Partnership.” Modi wrote an obituary titled ‘My friend, Abe-san’ in which he outlined his cherished memories of Abe since 2007, when Modi was still Gujarat’s chief minister. He noted that Abe was ahead of his time in global leadership and cited many of Abe’s initiatives, including the Quad.

With Abe’s untimely demise, India has lost a great friend and great champion. Abe is irreplaceable. Befittingly, India announced a day of national mourning in honour of Abe’s lasting contributions to India and its development in recent years.

. . . . .

Dr Purnendra Jain is a Visiting Senior Research Fellow-designate at the Institute of South Asian Studies (ISAS), an autonomous research institute at the National University of Singapore (NUS), and an Emeritus Professor in the Department of Asian Studies at the University of Adelaide, Australia. He can be contacted at purnendra.jain@adelaide.edu.au. The author bears full responsibility for the facts cited and opinions expressed in this paper.

[1] “Editorial: Time Abe came clean on party scandal that still dogs him at Diet”, The Asahi Shimbun, 6 January 2022, https://www.asahi.com/ajw/articles/14516289.

[2] Gregory Clark, “Shinzo Abe, his wife and North Korea”, John Menadue’s Public Policy Journal, 10 July 2022, https://johnmenadue.com/shinzo-abe-his-wife-and-north-korea/.

[3] Eileen Ng, “Assassination of Japan’s Shinzo Abe stuns world leaders”, AP News, 9 July 2022, https://apnews.com/article/shinzo-abe-shooting-world-leaders-react-e163d6212ab8a76ff88ac66a7287172c.

[4] “Statement by President Joe Biden, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese, and Prime Minister Narendra Modi Mourning Former Prime Minister Abe”, The White House, 8 July 2022, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/07/08/statement-by-president-joe-biden-prime-minister-anthony-albanese-and-prime-minister-narendra-modi-mourning-former-prime-minister-abe/.

[5] Shinzo Abe, “Asia’s Democratic Security Diamond”, Project Syndicate, 27 December 2012, https://www.project-syndicate.org/onpoint/a-strategic-alliance-for-japan-and-india-by-shinzo-abe.

[6] Purnendra Jain, “The Tokyo Quad summit shows the group is maturing, but the real tests are still to come writes Purnendra Jain”, Asialink, 1 June 2022, https://asialink.unimelb.edu.au/insights/quad-momentum-continues.

[7] Matthew P. Goodman, “Shinzo Abe’s Legacy as Champion of the Global Economic Order”, Center for Strategic and International Studies, 8 July 2022, https://www.csis.org/analysis/shinzo-abes-legacy-champion-global-economic-order.

[8] “Kyodo News Digest: 10 July 2022”, Kyodo News, 10 July 2022, https://english.kyodonews.net/news/2022/07/ece62282642e-kyodo-news-digest-july-10-2022–1-.html.

[9] “Abe says ‘atmosphere ripe’ for constitutional reform”, The Japan Times, 20 December 2021, https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2021/12/20/national/abe-says-atmosphere-ripe-constitutional-reform/.

[10] “Confluence of the Two Seas”, Speech by HE Mr Shinzo Abe, Prime Minister of Japan at the Parliament of the Republic of India, https://www.mofa.go.jp/region/asia-paci/pmv0708/speech-2.html

[11] “India-Japan Relations”, The Embassy of India, Tokyo, Japan, https://www.indembassy-tokyo.gov.in/eoityo_pages/MTgx; and https://www.in.emb-japan.go.jp/itpr_en/Japan_India_Relations.html.

[12] Akitaka Saiki, “Message from President Saiki-Shinzo Abe, Chairman of the Japan-India Association (former Prime Minister) mourns the sudden death”, Japan-India Association, https://www.japan-india.com/release/4a0a1003247391857306bea2e51b488709a96fbe.

[13] “Gravitas: Exclusive: Shinzo Abe backs strong India-Japan ties”, WION, 25 May 2022, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2xn_GeI7sGI.

-

More From :

More From :

-

Tags :

Tags :

-

Download PDF

Download PDF