Russia-Pakistan Economic Relations: Energy Partnership and the China Factor

Claudia Chia, Zheng Haiqi

6 October 2021Summary

On 15 July 2021, Russia and Pakistan signed the shareholders’ agreement and outlined the terms to construct a US$$2.5 billion (S$3.4 billion) natural gas pipeline in Pakistan. This project is a part of a Russian investment package worth of US$14 billion (S$18.7 billion) in Pakistan’s energy sector promised in 2019. Over the past decade, Russia and Pakistan have demonstrated strong political will and taken initiatives to enhance trade cooperation. Pakistan’s pursuit of economic redemption and energy supplies, plus the Russian aspiration to expand its economic footprints in Asia bring the two countries together. This paper discusses Russia’s growing economic interests in Pakistan in the context of its wider eastward shift to Asia and how Pakistan, with its crippling economy and strained ties with the West, stands to gain from this engagement.

Introduction

Driven by concerns regarding China’s growing economic prowess and the deepening of United States (US)-India relations, Russia has developed a new interest in engaging with Pakistan. Following the conclusion of the Russia-Pakistan Technical Committee meeting in 2020, both countries revived discussions on the North-South Gas Pipeline Project. The project was initially inked in 2015, but it was put on hold due to Western sanctions imposed on Rostec, a Russian state-controlled company that was a stakeholder.[1] Now, the project has been renamed the PakStream Gas Pipeline Project (PSGP). The 1,100 kilometres PSGP is scheduled to complete in 2023 and will transport liquefied natural gas (LNG) from terminals in Karachi and Gwadar to Lahore. According to the agreement signed in July 2021, Moscow gave Islamabad a majority stake in the project (74 per cent) and pledged to help Pakistan with expertise and funding. The PSGP is one of the largest Russian investments in Pakistan since the Soviet Union assisted in developing the Oil and Gas Development Company and Pakistan Steel Mills in the 1960s and 1970s.

With China taking precedence on the geopolitical stage, Russia and Pakistan are confronted with a major power in their immediate vicinity. Both governments recognise the need to adapt their foreign policy priorities in light of China’s rise and its potential impact on the regional balance of power. Furthermore, the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), launched in 2013 as the flagship project of the China-led Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) saw US$62 billion (S$83 billion) worth of investment and infrastructure expansion flowing into Pakistan. The CPEC is a bright economic prospect that Russia cannot afford to overlook as it seeks to develop and expand its economic connections with Asia.

Russia’s desire to look eastward and engage Asia is not a new phenomenon, having been propounded during Mikhail Gorbachev’s leadership in the 1980s and 1990s. In 2010, Moscow officially announced “the turn to the East” (povorot na vostok). The rhetoric gained traction as one of President Vladimir Putin’s key objectives during his 2012 election campaign. Under Putin, Russia has advanced a new strategy for its geopolitical resurgence by re-orientating the ‘Greater Europe’ project to the ‘Greater Eurasian Partnership’. Russia envisages a new Asian policy that highlights its unique geopolitical position – being both European and Asian – and seeks to create “a shared space for economic, logistic, and information cooperation, peace, and security from Shanghai to Lisbon and from New Delhi to Murmansk.”[2] However, the eastward gaze has been China-centric; strategic and economic links between Russia and the rest of Asia remain nominal. In 2012, Russia accounted for only one per cent of the total trade in the Asia-Pacific region.

Things changed in 2014 when the West condemned Russia’s annexation of the Crimean Peninsula, leading to harsh Western sanctions and Russia’s expulsion from the G8. The sanctions, combined with falling oil prices and deteriorating relations, led to a decline in trade between Russia and the European Union (EU), Moscow’s largest trading partner. Facing increasing isolation from the West and the loss of the EU as a strategic partner, Russia was forced to seek new security and economic partners in Asia. As scholar Bobo Lo puts it, “[If] Asia has mattered, then it has largely been because of its relevance to Russia’s interaction with the West, and by extension, its position in the world.”[3]

Having joined the American-sponsored Southeast Asian Treaty Organization (1954) and the Central Treaty Organization (1955), Pakistan was aligned with the US during the Cold War and had different interests and objectives vis-à-vis the Soviet Union. Pakistan-Soviet interactions were sparse with a few agreements inked on trade, assistance, military cooperation and cultural exchange during the 1960s. Despite having helped secure the Tashkent Declaration between India and Pakistan in 1966, the Soviet Union continued to utilise its veto power at the United Nations (UN) to block critical resolutions to affirm its support for India’s stance on Kashmir. The support irked Pakistan and added to the trust deficit between Islamabad and Moscow.

Moreover, the Soviet Union’s backing of Indian operations in the 1971 India-Pakistan War and the signing of the Indo-Soviet Treaty of Peace, Friendship and Cooperation in the same year evinced its preference for working with India. In March 1972, Pakistani President Zulfikar Ali Bhutto visited Soviet leaders in Moscow in attempt to normalise relations. This visit was a success in many regards as relations and trade were restored, and Bhutto acquired Soviet assistance to build a steel mill in Karachi, the largest industrial project in Pakistan at the time. He followed up with an official visit in 1974 under his term as prime minister and bilateral relations continued to grow. However, the relationship dived to a deep end following the military coup by General Zia-ul-Haq in July 1977 and the Pakistan-US allied fight against the Soviet Union in Afghanistan in the 1980s.

Since the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, Russia has tried to develop ties with Asia and steps were taken between Russia and Pakistan from the late 1990s onward to improve ties. Rebuilding relations was a slow and difficult process as Moscow was suspicious of Islamabad’s support for terrorism and apprehensive of the close Pakistan-US ties. Divergences between Islamabad and Washington following the 9/11 attacks, as well as the subsequent US tilt toward India under the Obama administration (2009-2016), impelled Pakistan to find alternate partners. The estrangement by the US has created openings for Russia to step in to engage Pakistan.

Furthermore, India’s participation in the American-led Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, which Russia slammed as a “aggressive and devious policy”, raises Russian worries that its longstanding South Asian partner is shifting allegiance to the US.[4] The Kremlin’s efforts to engage Pakistan, India’s adversary, may be a signal to New Delhi that Moscow too has other options. Moscow and Islamabad have found themselves on the same side of geopolitical competition, and their burgeoning bilateral relations are a testament to their responses to contemporary geopolitical realities.

Economic Ties between Russia and Pakistan

The rapprochement between Russia and Pakistan began in the early 2000s, first marked with the state visit of Alexander Losyukov, Russian Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs, to Pakistan in April 2001 and the reciprocal visit by Pakistani President Pervez Musharraf to Russia in February 2003. The Pakistani withdrawal of support for the Taliban regime and participation in the US-led international security effort into Afghanistan led to a thaw in the icy Russia-Pakistan relations. Musharraf was the first Pakistani head of state to visit Moscow since Bhutto in 1970. These visits did not garner much success and bilateral relations did not pick up.

Four years later, Russian Prime Minister Mikhail Fradkov paid an official visit to Islamabad in an attempt to reactivate relations but yielded little results. One positive outcome was the earmarking of Pakistan as an “important regional player” with whom Russia should develop bilateral and multilateral relations with in the 2008 Russian Foreign Policy Concept.[5] Despite the fact Pakistan was not mentioned in the newer Foreign Policy Concept renditions in 2013 and 2016, there has been an upward trend in high-level ministerial visits, military and economic cooperation between the two countries since 2010.

Under the leadership of Russian President Dmitri Medvedev and Pakistani President Asif Ali Zardari, there were increased interactions and meetings bilaterally and alongside multilateral events. At the Sochi summit in 2010, both Presidents sowed the idea for a Russia-Pakistan Inter-Governmental Commission (IGC) on Trade, Economic, Scientific and Technical Cooperation. The inaugural meeting was held in the following month and annual sessions have been held ever since. During Zardari’s official visit to Russia in 2011, he told Medvedev that “[We] are very close neighbours, we are in the same region. Our borders don’t touch but our hearts do.”[6] Both sides emphasised the need of expanding economic cooperation and enhancing joint counterterrorism efforts.

The meeting of Prime Ministers Syed Yusuf Raza Gilani and Putin on the sidelines of the 10th Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) Heads of Government Meeting in November 2011 was another key milestone in the development of Pakistan-Russia relations. Both parties discussed a free trade agreement (FTA) and currency arrangement to facilitate bilateral trade and strengthen economic relations. The meeting highlighted Pakistan’s increasing significance in the Russian eyes, with Putin stating that “Pakistan is our major trade and economic partner and an important partner in South Asia and the Muslim world.” [7] He also offered Islamabad assistance in expanding the Pakistan Steel Mills, technical support to power plans in Guddu and Muzaffargrah, and expressed Russian interest in joining the CASA-1000 megaproject involving Central Asia and Pakistan.

More memoranda in metallurgy, railways and power were signed during the subsequent visit of Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov to Islamabad in 2012. Putin personally dispatched Lavrov to Islamabad after he had to cancel his trip due to a busy schedule. By the end of 2012, the bilateral trade volume had grown six-fold compared to the beginning of 2000s. In 2013, there was a breakthrough in bilateral relations with the establishment of the first Russia-Pakistan Strategic Dialogue. Since then, there have been non-stop high-level contacts, a series of joint military exercises, the lifting of Russian self-imposed arms embargoes on sales to Pakistan and trade discussions across many levels of ministries, business and military.

The US announcement of troops withdrawals from Afghanistan from 2014 further motivated Russia to improve relations with Pakistan, which it perceived as a key security partner in the region. In January 2018, the State Bank of Pakistan and the Central Bank of Russian Federation inked a memorandum of understanding on bilateral banking cooperation. As a result, bilateral trade increased from US$442 million (S$593 million) in 2017 to U$532 million (S$714 million) in 2018.[8]

The resolution of a four-decade trade dispute caused by the disintegration of the Soviet Union in November 2019 was perhaps the clearest signal yet of mutual commitment to deepen economic ties. Having started negotiations in 2016, Pakistan eventually paid US$93.5 million (S$125 million) to Russia, clearing the path for a fresh slate of economic engagement.[9] Shortly after, Denis Manturov, Russian Minister of Industry and Trade, led a 64-member business delegation on an official four-day visit to Islamabad to explore various areas of economic cooperation and investment with Pakistani counterparts. In 2020, the bilateral trade volume reached a record high of US$790 million (S$1 billion), a substantial increase of more than 45 per cent from 2019.[10] Imran Khan, Pakistan’s current prime minister, has also been courting Russian businessmen in Islamabad for collaboration in the manufacturing, railways and energy sectors.[11]

Pakistan as Russia’s New Energy Client

Widely referred to as an ‘energy superpower’, Russia is the world’s leading natural gas exporter and second-largest oil exporter. It has long been the EU’s principal supplier of natural gas and petroleum. However, as Europe moves toward decarbonisation and renewable energy under the European Green Deal, Russia needs to find new markets for its energy products.

Additionally, the EU’s anxiety of becoming overtly dependent on Russian energy supplies is palpable. Russia cut gas supply to Ukraine in 2006, 2009 and 2014 due to pricing disagreements and political differences, causing disruptions to several EU countries relying on the same supply lines. Similarly, Russia suspended oil deliveries to Belarus due to a contractual dispute in January 2020. These incidents underscore the bloc’s ‘structural scarcity’ and the Russian dominance in energy security. The EU has sought to diversify its external partners and develop alternative energy corridors to reduce reliance on Russia. Between 2016 and 2020, the share of energy products in Russia’s total exports to the EU fell from 60.8 per cent to 55.3 per cent.[12] While Russia continues to be the EU’s main supplier, its total share of critical energy imports has decreased.

The EU’s quest for energy security has complex geopolitical entanglements that will be tough to overcome. For example, the Nord Stream 2 (NS2) gas pipeline from Russia to Germany has met opposition from countries such as the US, Ukraine and Poland. In January 2021, the Donald Trump administration-imposed sanctions on Russian firms involved in the NS2 project. President Joe Biden overturned these sanctions in May 2021 and secured an agreement with Germany in July 2021 where Berlin promised to retaliate if Moscow attempts to use energy as a ‘weapon’ against the European states.[13] However, a month later, the Biden administration again placed sanctions on Russian entities while retaining a waiver for the company in charge of NS2 construction. Despite that Russia’s inexpensive energy supply has been critical to meeting European demand and economic development, the European threat perception of Russia remains high.

The COVID-19 pandemic took a toll on the Russian economy, causing it to contract by three per cent in 2020. The decline in global energy demand and rising oil prices further contributed to the weakening of the ruble.[14] As the Russian economy depends heavily on the revenue generated from the sales of natural gas and petroleum, Moscow needs to look for new markets. In this regard, Pakistan, which is facing a gas shortage, emerges as a viable energy consumer.

Currently, Pakistan has a gas shortfall of 1.5 billion cubic feet per day (bcfd), which would double by 2025.[15] Authorities estimated that domestic gas supplies would drop from 3.51 bcfd in 2019 to 1.67 bcfd in 2028, necessitating an increase in LNG imports to meet demand.[16] The country began importing LNG in 2015 to mitigate growth in consumption and to reduce oil import. Over a mere six years, Islamabad has become the world’s ninth largest LNG importer. Qatar is presently Pakistan’s biggest gas supplier, and the latter is still looking for more energy partners to cooperate with. In June 2021, Pakistan secured US$4.5 billion (S$ 6.12 billion) worth of financing from the Islamic Trade Finance Corporation to cover import costs of crude, petroleum and LNG.

Rising power tariffs, power shortages, inefficient plants, theft and corruption are daunting difficulties facing Pakistan’s energy and power sector. In 2020, the National Electric Power Regulatory Authority of Pakistan urged Khan to declare a national power emergency and implement drastic reforms. This request came after a series of increase in power tariffs and the accumulation of circular debt to PKR 1.9 trillion (S$15 billion).[17] New power generation projects under the CPEC were expected to help Pakistan address its energy deficiency, but there are concerns regarding corruption, contract violations and whether Chinese-led energy investments can help Pakistan reduce dependence on oil. Another worry is inefficiency and poor quality as these projects use the existing distribution lines which have not been upgraded.

Russia is eager to welcome Pakistan as a new energy client as it plans to triple its LNG production capacity and increase LNG exports by 2035. Besides the PSGP, Russian companies have filed proposals to supply more LNG to Pakistan. Lavrov highlighted in his visit to Islamabad in April 2021 that Rosatom and the Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission are exploring cooperation in using nuclear energy for medicine and industry purposes. This visit marks an improvement in Moscow-Islamabad relations as he last visited Pakistan nine years ago. Prior to Lavrov’s visit, Pakistan’s Ambassador to Russia, Shafqat Ali Khan, stated in a webinar that both countries “are marked by deepening trust and expanding win-win cooperation.”[18]

Potential in Linking the EAEU and BRI

According to the latest UN World Investment Report, Pakistan received around US$2.1 billion (S$2.82 billion) of foreign direct investment (FDI) in 2020. This figure is practically negligible when compared to India’s FDI influx of US$64 billion (SG$85.9 billion), despite the world economy being hit by the pandemic.[19] External investment and assistance, particularly from China, have been significant to Pakistan’s economic and industrial development. Nevertheless, Islamabad has struggled to attract investments over the years.

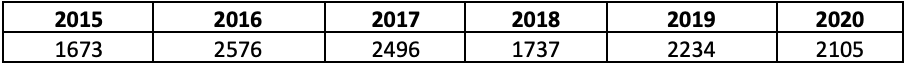

Table 1: Pakistan’s FDI inflow 2015-2020 (in US$ millions)

Source: UN World Investment Report 2021, https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/wir2021_en.pdf

In this aspect, the Russian efforts to integrate the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) with the BRI present Pakistan with a tremendous opportunity to attract more investments. In 2016, Putin proposed a ‘Greater Eurasia Partnership’, encompassing the EAEU member states, China, India, Pakistan, Iran and the Commonwealth nations. As the EAEU and the BRI share the same aim of unifying Eurasia through overland trade and infrastructure, Moscow and Beijing have inked agreements indicating collaboration and regional integration since 2015.

Pakistan was dubbed by analyst, Andrew Korybko as the “zipper of Pan Eurasian Integration” across South, Central and West Asia;[20] it is a strategic location capable of providing a stable oil supply and achieving the Russian geo-economic vision of a “Greater Eurasia”. Korybko and other Russian analysts have proposed Moscow’s participation in the CPEC.[21] In 2016, then-Russian Ambassador to Pakistan, Alexey Devoc, allegedly commented that Russia “strongly supported” the CPEC and Moscow and Islamabad had discussed the merger of EAEU with CPEC.[22] Moreover, Pakistani authorities have agreed to grant Russian access to the Chinese-built Gwadar Port. This gives Russia and Central Asia access to the Persian Gulf, Arabian Sea and Indian Ocean. Additionally, the port serves as an alternative trade route in case of blockage along the Straits of Malacca in Southeast Asia.

At the C5+1 International Conference of Central and South Asia in July 2021, Lavrov expressed interest in aligning the energy infrastructure of Central and South Asia by participating in more energy and infrastructure projects in the region, such as the Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India gas pipeline. He voiced Russia’s commitment to “create an interconnected space between the Commonwealth of Independent States and the SCO.”[23] The recent announcement by the Taliban to participate in the CPEC presents another opportunity for Russia to join hands with Pakistan and China to rebuild Afghanistan. The EAEU-BRI dynamics would offer an existing framework for regional countries to invest in Afghanistan and deepen regional economic connectivity.

Challenges

While the conjugation of the EAEU-BRI in Central and South Asia would benefit Russia and Pakistan by connecting markets, the projects may build a continental stronghold for China and tip the regional balance in Beijing’s favour.[24] In 2017, Beijing’s trade with Central Asia reached US$30 million (S$40 million), almost double that of Moscow’s trade in the area. Joint EAEU-BRI might see an expansion of Chinese presence in the landlocked region, further dwindling Russian influence. So far, no EAEU-BRI projects have been implemented, raising doubts on the intentions of Moscow and Beijing. While Russia’s official rhetoric maintains support for the BRI and CPEC, Russia has been signing its own energy deals with Islamabad and boosting bilateral ties with Pakistan on its own terms.

Despite the close Russia-China strategic partnership with Presidents Putin and Xi Jinping supposedly “best friends”, many have believed Moscow has settled into a junior partner status vis-à-vis Beijing.[25] The bilateral trade balance has been in China’s favour for many years.[26] While Beijing is Moscow’s largest trading partner, Moscow is not in the former’s top 10 list. Many China-led projects in the resource-rich Russian Far East, which shares a 4,000 kilometres border with China, are reportedly lagging in development or existing merely on paper.[27] The Kremlin has been careful to restrict foreign investments into strategic resources and critical infrastructures, thereby limiting the expansion of Chinese investments.

Moscow is likewise concerned with Beijing’s increasing assertiveness in foreign policy and improved economic and military capabilities. In 2017, Russia initiated the expansion of the SCO membership to India to dilute Chinese dominance in the organisation; China responded that this would be possible on the condition that Pakistan too joined as a member. In another attempt to maintain strategic autonomy and to check China, Russia continued supplying military equipment to India despite Chinese reservations during the India-China dispute over the Himalayan border in May-June 2020.

Moving forward, the Kremlin will find it difficult to balance between India, Pakistan and China. Given the changing geopolitical and economic realities, a tripartite alliance between China, Russia and Pakistan may be in development. The tri-power configuration could curtail Indian dominance in South Asia. India has consistently refused to join the BRI and views China’s encroachment into its neighbourhood as hostile. The passing of the CPEC through Pakistan-administered Kashmir remains an intolerable thorn for India.

For Islamabad, getting closer to Russia and China would render more security gains especially given the current state of uncertainty in Afghanistan. However, Pakistan needs to navigate carefully between Russia-China economic competition particularly in its energy market and avoid colouring its relations with Moscow with historical baggage and through the lens of India.[28]

The asymmetry of Pakistan-China economic relations, the issue of indebtedness, the lack of opportunities for local firms, and the perceived intrusion of Chinese companies are divisive and thorny problems for Islamabad. Over the years, series of protests, killings of Chinese workers and property destructions have threatened China’s activities across Pakistan. Twelve people were killed in a suicide attack on a bus near the Dasu hydropower plant in northern Pakistan in July 2021, nine of whom were Chinese nationals. The plant was assumed to under the CPEC, but it was actually a World Bank-funded cooperative venture. Usually, Pakistani paramilitary officials are deployed to protect CPEC projects and Islamabad is now providing security in all projects involving Chinese personnel. Despite the government’s reassurance that Chinese investments will help Pakistan, domestic dissatisfaction with the Chinese presence has not abated. In this climate of mistrust, news of the EAEU merging with CPEC would not be received well.

Both Russia and Pakistan have weak economies and underwhelming financial performances. Moscow remains subjected to heavy Western sanctions, making it difficult to pursue more commercial ventures. The Pakistani economy is stranded in external debt due to its reliance on loans from international funding institution. Around 35 per cent of Pakistan’s expenditure goes to repaying debt.[29] To alleviate its debt, Islamabad is speaking with the International Monetary Fund for a US$6 billion (S$8 billion) bailout programme, but fiscal deficits remain difficult to solve in the long run.

Conclusion

Given China’s expanding economic footprint and influence in South and Central Asia, Pakistan and Russia will likely desire to lessen their economic dependency on China. Thus, it is in their best interests to strengthen bilateral economic cooperation. Russia, with its abundance of natural and human resources, possesses huge potential to grow economically. Beyond South and Central Asia, Moscow has taken its eastward pivot actively by pursuing FTAs with Southeast Asia such as Vietnam (2016) and Singapore (2019). As Russia’s economic footprint in Asia is still relatively low, Pakistan can capitalise on this opportunity to expand cooperation and attract Russian investments.

While it will take a long time for Pakistan to become Russia’s key economic partner, the trend of strong bilateral willingness to strengthen ties is unlikely to cease. As the IGC convenes its seventh session later this year in Moscow, one can expect representatives from both countries to announce more trade and investment initiatives.

. . . . .

Ms Claudia Chia is a Research Analyst at the Institute of South Asian Studies (ISAS), an autonomous research institute at the National University of Singapore (NUS). She can be contacted at claudiachia@nus.edu.sg. Mr Zheng Haiqi is a PhD Candidate in the School of International Studies, Renmin University, China, and a Visiting Scholar at ISAS. He can be contacted at zheng.haiqi@nus.edu.sg. The authors bear full responsibility for the facts cited and opinions expressed in this paper.

[1] Mifrah Haq, “Russia warms to Pakistan after three decades of cold ties”, Nikkei Asia, 20 July 2021, https://asia.nikkei.com/Politics/International-relations/Russia-warms-to-Pakistan-after-three-decades-of-cold-ties.

[2] Marina Glaser (Kukartseva) and Pierre-Emmanuel Thomann, “The Concept of ‘Greater Eurasia’: The Russian ‘Turn to the East’ and Its Consequences for the European Union from the Geopolitical Angle of Analysis”, Journal of Eurasian Studies, (July 2021): 4.

[3] Bobo Lo, Russia and the New World Disorder (Washington, D.C: Brookings Institution Press, 2015), p. 132.

[4] Suhasini Haidar, “Russia says U.S. playing Quad ‘game’ with India”, The Hindu, 9 December 2020, https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/russia-says-us-playing-quad-game-with-india/article33291351. ece.

[5] The Foreign Policy Concept of The Russian Federation, 12 January 2008, The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation, http://en.kremlin.ru/supplement/4116.

[6] Meeting with President of Pakistan Asif Ali Zardari, 12 May 2011, Presidential Executive Office, http://en. kremlin.ru/events/president/news/11224.

[7] Prime Minister Vladimir Putin meets with Prime Minister Syed Yousuf Raza Gilani of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, Government of the Russian Federation, 7 November 2011, http://archive.government.ru/eng/ docs/16991/.

[8] “Pakistan, Russia trade lower than potential”, The Express Tribune, 10 October 2019, https://tribune.com. pk/story/2076114/2-boosting-ties-pakistan-russia-trade-lower-potential.

[9] Zafar Bhutta, “Pakistan settles Soviet-era trade dispute with Russia”, The Express Tribune, 7 November 2019, https://tribune.com.pk/story/2095099/2-pakistan-settles-decades-old-trade-dispute-russia.

[10] Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov’s remarks and answers to media questions at a joint news conference with Foreign Minister of Pakistan Makhdoom Shah Mahmood Qureshi, Islamabad, 7 April 2021, The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation, https://www.mid.ru/en/foreign_policy/news/-/asset_publisher/ cKNonkJE02Bw/content/id/4666612.

[11] “PM Imran Khan calls on leading Russian businessmen to discuss industrial cooperation”, The News International, 19 April 2021, https://www.thenews.com.pk/latest/822793-pm-imran-khan-calls-on-leading-russian-businessmen-to-discuss-industrial-cooperation.

[12] “EU imports of energy products”, Eurostat, June 2021, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=EU_imports_of_energy_products_-_recent_developments&oldid=512866.

[13] “Nord Stream 2: Russia’s push to boost gas supplies to Germany”, Reuters, 6 September 2021, https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/nord-stream-2-difficult-birth-russias-gas-link-germany-2021-05-20/.

[14] “Russia’s economy shrank 3% last year”, Reuters, 2 April 2021, https://www.reuters.com/article/russia-economy-idUSR4N2LK05S.

[15] Viktor Katona, “Qatar Looks To Dominate This Very-Fast Growing Gas Market”, Oilprice, 6 April 2021, https://oilprice.com/Energy/Natural-Gas/Qatar-Looks-To-Dominate-This-Very-Fast-Growing-Gas-Market.html.

[16] Khaleeq Kiani, “The LNG trilemma”, Dawn, 25 January 2021, https://www.dawn.com/news/1603381.

[17] Kiani, “Nepra urges prime minister to declare power emergency”, Dawn, 2 March 2020, https://www. dawn.com/news/1537725.

[18] “Islamabad, Moscow have developed strategic trust”, Dawn, 31 March 2021, https://www.dawn. com/news/1615582/islamabad-moscow-have-developed-strategic-trust-envoy.

[19] Nasir Jamal, “Falling further behind”, Dawn, 9 August 2021, https://www.dawn.com/news/1639563.

[20] Andrew Korybko, “Pakistan Is The “Zipper” Of Pan-Eurasian Integration”, Russian Institute for Strategic Studies, 15 September 2015, https://en.riss.ru/article/1018/.

[21] “Pakistan’s Role in Russia’s Greater Eurasia Partnership”, Russian International Affairs Council, 3 June 2020, https://russiancouncil.ru/en/analytics-and-comments/analytics/pakistan-s-role-in-russia-s-greater-eurasian-partnership/.

[22] “Russia makes U-turn, backs China-Pak Economic Corridor; India alarmed”, Deccan Chronicle, 19 December 2016, https://www.deccanchronicle.com/nation/current-affairs/191216/russia-makes-u-turn-backs-china-pak-economic-corridor-india-alarmed.html.

[23] Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov’s remarks at a plenary session of the international conference Central and South Asia: Regional Connectivity. Challenges and Opportunities, Tashkent, July 16, 2021, The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation, https://www.mid.ru/en/web/guest/meropriyatiya_s_uchastiem_ ministra//asset_publisher/xK1BhB2bUjd3/content/id/4814877.

[24] Michael Clarke, “The Neglected Eurasian Dimension of the ‘Indo-Pacific’: China, Russia and Central Asia in the Era of BRI”, Security Challenges 16, no. 3 (2020): 35.

[25] Isaac Stone Fish, “Why does everyone assume that Russia and China are friends?”, The Washington Post, 26 May 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2021/05/26/why-does-everyone-assume-that-russia-china-are-friends/.

[26] Jonathan Hillman, “China and Russia: Economic Unequals”, Center for Strategic & International Studies, 15 July 2020, https://www.csis.org/analysis/china-and-russia-economic-unequals.

[27] Dimitri Simes Jr and Tatiana Simes, “Moscow’s pivot to China falls short in the Russian Far East”, South China Morning Post, 29 August 2021, https://www.scmp.com/week-asia/politics/article/3146505/ moscows-pivot-china-falls-short-russian-far-east.

[28] Ume Farwa, “Russia’s Strategic Calculus in South Asia and Pakistan’s Role: Challenges and Prospects”, Strategic Studies 39, no. 2 (2019): 45.

[29] Asif Shahzad and Gibran Naiyyar Peshimam, “Pakistan, under IMF bailout, sets 4.8% GDP growth target”, Reuters, 11 June 2021, https://www.reuters.com/article/pakistan-economy-budget-idUSL2N2NT0WI.

-

More From :

More From :

-

Tags :

Tags :

-

Download PDF

Download PDF