Prime Minister Imran Khan’s Visit to Sri Lanka: Current Ties and Future Partnership

Chulanee Attanayake

1 April 2021Summary

Pakistan’s Prime Minister Imran Khan travelled to Sri Lanka for a two-day visit on 23 February 2021. The visit was his maiden visit to the island nation after becoming prime minister in 2018. He was also the first head of state to visit Sri Lanka since President Gotabaya Rajapaksa assumed power in November 2019. Though there were some controversies prior to his arrival, he was welcomed with much fanfare in Colombo. Against this backdrop, this paper examines current bilateral relations and explores future partnership between the two countries.

Sri Lanka-Pakistan Relations

Sri Lanka and Pakistan share a long history of culture and friendship. Their relationship is rooted deep in history and goes back to the pre-Islamic era. Buddhism has flourished in areas that later became Pakistan. A historical narrative notes that Mohammad bin Qasim, the Arab military commander of the Umayyad Caliphate who led the Muslim conquest of Sindh and Multan, came to Sindh in the 8th century to rescue widows of Arab settlers in Serendib (ancient Sri Lanka), marking the advent of Islam in this region.1 Sri Lankan Muslims also supported Pakistan’s struggle for a separate homeland during the colonial period.2 Since then, traditions of goodwill between the two countries have continued.

At the time of Sri Lanka’s independence in 1948, Quaid-e-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah, the founding father of Pakistan, noted that “Pakistan has the warmest goodwill towards Ceylon, and I am sanguine that the good feelings which exist between our people will be further strengthened as the years roll by and our common interests, and mutual and reciprocal handling of them, will bring us into still closer friendship.”3

Post-independent bilateral relations between the two countries were marked by mutual understanding and forging of close diplomatic ties. The two countries’ mutual concern and fear vis-à-vis their big neighbour India have laid the foundation for a strong relationship.4 Despite not subscribing to a common border, a common culture or a common religion, Colombo and Islamabad are experiencing a growing and problem-free mutual relationship that did not necessitate frequent meetings between their governments’ heads.5

Political Relations

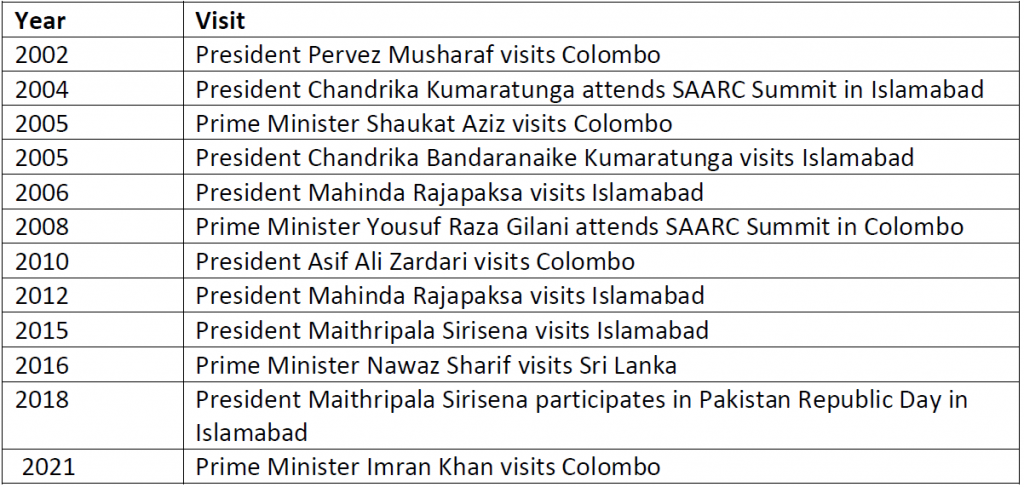

Since establishing official diplomatic ties in 1948, both Sri Lanka and Pakistan have shared cordial diplomatic relations. The first visit by a Sri Lankan head of state to Pakistan was made in the same year by Prime Minister D S Senanayake. Since then, seven Sri Lankan heads of state visited Pakistan and three Pakistani heads of state visited Sri Lanka between 1948 and 2000.6 The high-profile visits between the two countries’ leaders have been more frequent in the last two decades (Table 1).

Table 1: Bilateral Visits by Presidents and Prime Ministers (2000-2020)

Source: Compiled from various issues of ‘Pakistan Foreign Policy – A Quarterly Survey’, Pakistan Horizon

Pakistan has always had a cooperative attitude towards Sri Lanka7 and the two countries have rendered mutual diplomatic assistance whenever needed during testing times. Sri Lanka played an important role in Pakistan’s restoration to the Commonwealth in 1989, following its departure from the organisation in 1972 in protest of recognising Bangladesh. Moreover, Colombo was vocal in Pakistan’s protest against Soviet military intervention in Afghanistan.8

Pakistan has reciprocated Sri Lanka’s goodwill at a crucial time in the post-war period. During multiple sessions of the United Nations Human Right Council (UNHRC) in Geneva, where multiple resolutions were tabled against Sri Lanka alleging war crimes, Pakistan’s support has been crucial. During the 25th UNHRC session in 2014, which called for an international inquiry into the alleged war crimes in Sri Lanka, Pakistan not only voted in favour of Sri Lanka, but it also made a strong statement defending Sri Lanka’s sovereignty and the predicaments of the proposed resolution.9 As the only Islamic nuclear state with a prominent influence in the Organization of Islamic Countries (OIC), Pakistan supported Sri Lanka in getting Muslim countries’ support.

Military Relations

It is not an exaggeration that defence ties and military cooperation are the cornerstone of Sri Lanka-Pakistan bilateral relations. Mutual support for defence and the military goes back to 1971 when Sri Lanka provided transit and refuelling facilities to Pakistani planes during the Pakistan-Bangladesh war. According to Sabiha Hasan (1985), who provides one of the most detailed accounts of bilateral relations in the early decades, Pakistan International Airlines aircrafts made 143 landings in Colombo between March and April 1971. Moreover, Pakistani air force planes touched down 31 times in Katunayake – 15 were westward bound and 16 were eastward.10 This was noteworthy as this decision was made at the expense of undermining Colombo’s relations with India.

Almost three decades later, Pakistan reciprocated when Sri Lanka was embroiled in the Elephant Pass battle.11 According to some publicly available records, Islamabad provided high-technology military equipment, flew fighter pilots on air strike missions on the Liberation Tiger of Tamil Eelam (LTTE ) bases and positioned some of its highly-trained army officers in Colombo to assist Sri Lanka in defeating terrorism.12 Pakistan has been among the largest suppliers of high-technology military equipment. In 2008, then Army Chief General Sarath Fonseka finalised a deal to purchase 22 Al-Khalid main battle tanks for Sri Lanka worth US$100 million (S$133.2 million) during his visit. Moreover, weaponry worth about US$65 million (S$86.60 million) for the Sri Lanka Army and Sri Lankan Air Force (SLAF) was ordered during this visit.13 However, these figures do not correlate with the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute’s calculations that show Pakistan’s arms exports to Sri Lanka to be US$4 million (S$5.32 million) between 1990 and 2019. In August 2008, some media reported that Pakistan Air Force pilots had participated in several successful airstrikes against several LTTE military bases.14 The SLAF later refuted these reports.15 Nevertheless, analysts reiterate that Pakistan’s support was vital to defeat the LTTE in Sri Lanka. The Business Standard noted that unlike India, Islamabad had no reservations in providing state-of-the-art weaponry to the Sri Lankan army to accelerate its counter-insurgency operationsagainst the LTTE. Sinharaja Tammita-Delgoda explains in Review Essay: Sri Lanka’s Ethnic Conflict – How Eelam War IV was Won by Maj Gen Ashok V Mehta that Sri Lanka’s winning formula was cobbled together with the support of China and Pakistan.

Pakistan also provides military training facilities for Sri Lanka’s military personnel at its premier defence colleges. It is estimated that around 200 Sri Lankan officers undergo training in Pakistan at any given time.16 The number of Sri Lankan military officers getting trained in Pakistan increased17 after India’s training opportunities were lowered due to political pressure from Tamil Nadu.18

Trade Relations

As an enhancement of the growing political relationship, Sri Lanka and Pakistan began economic ties by signing a long-term trade agreement in May 1955.19 The agreement provided for the most-favoured nations status for each other and offered mutual consultation when necessary for trade matters. The agreement was replaced in 1984 with a new one that showcased their resolve to strengthen and diversify bilateral trade. The Sri Lanka-Pakistan Business Council was established in 1991, which was later incorporated as the Pakistan-Sri Lanka Business Forum in 2005. The two countries signed a Free Trade Agreement (FTA) in June 2005. With that, Sri Lanka became the first country to sign an FTA with Pakistan. The FTA provides 100 per cent duty concession on 206 commodities from Sri Lanka. Sri Lanka waived duties on 102 items. With that, bilateral trade has increased by 27 per cent, making Pakistan Sri Lanka’s second-largest trade partner in South Asia. Bilateral trade, which was US$169 million (S$225.18 million) in 2005, has risen to US$345 million (S$486.34 million) in 2011.20 According to the Central Bank of Sri Lanka, Colombo’s imports from Pakistan in 2019 amounted to US$370 million (S$492.95 million), and its exports were US$82 million (S$109.25 million).

The 2021 Visit

Prime Minister Imran Khan made a state visit to Colombo on 23 and 24 February 2021 at the invitation of Sri Lanka’s Prime Minister Mahinda Rajapaksa. He was accompanied by a high-level delegation comprising federal ministers and senior government officials. Even though this was not Khan’s first visit to Sri Lanka, as he last visited Colombo in 1986 as the Pakistan cricket captain, it was his first official visit after assuming power as Pakistan’s prime minister. It is also the first visit by a head of state to Sri Lanka after President Gotabaya Rajapaksa formed the new government in November 2019.

Khan held delegation-level meetings with Gotabaya and Mahinda. During the meetings, the two countries comprehensively reviewed the multifaceted bilateral relationship in diverse fields of cooperation. Khan and Gotabaya discussed issues at length, sharing technical know-how on promoting agriculture in both countries.21 Both the prime ministers also discussed the enhancement of bilateral cooperation in trade and other areas such as defence, science, and technology.22

The joint communiqué read that the visit offered a timely opportunity to further close ties and regular consultations; particularly in the areas identified during the recently held foreign secretary-level bilateral political consultations, Joint Economic Commission session, and the commerce secretaries-level talks.23

The visit saw apriority and focus on enhancing trade and commercial relations. Khan promoted the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) and proposed exploring the possibility of connecting Sri Lanka with the Central Asian region through it.24 Sri Lanka was also offered a US$50 million (S$66.62million) new credit line for cooperation in the field of defence and security.25 Another PKR52 million (S$0.44 million) was offered to promote sports in Sri Lanka, including through training and equipment.26 Khan also inaugurated the High-Performance Sports Complex in Colombo.

Sri Lanka and Pakistan share their strongest bond in defence and sports. Apart from the longstanding defence cooperation explained above, Sri Lankans fondly remember Pakistan and Khan for their cricket legacy. The support Pakistani fans gave the Sri Lankan team during the 1996 World Cup is remembered with gratitude. Pakistani players joined the Indian team for a friendly match in Colombo just before the 1996 Cricket World Cup when both the West Indies and Australia refused to participate in the first round fixtures due to a recent bombing incident.27 During the final match against Australia in Lahore, Pakistani fans cheered the Sri Lankan team giving it moral support. Sri Lanka reciprocated in 2009 by sending its team to Pakistan despite security warnings in order to prevent the latter from being isolated in the field of international cricket. The warnings were proven right when the bus carrying the team was attacked by 12 militants wielding automatic weapons en route to Lahore’s Gaddafi Stadium. However, the goodwill remained and the Sri Lankan team resumed its tours to Pakistan in 2017 and 2019.

One of the key highlights of the state visit was Pakistan’s focus on its Buddhist heritage. Taxila, a significant archaeological site in Punjab, is a reminder of Pakistan’s Buddhist history. Gandhara, the centre of historic Buddhist art, was situated in present-day Peshawar in northwest Pakistan. It is believed that Pali, the language in which the canons of Theravada Buddhism have been preserved in Sri Lanka, was spoken in some areas of what Pakistan constitute today. According to some scholars, after the Partition in 1947, the pre-Islamic history of Buddhist sculptures and other artefacts were used as instruments of nation-building and forged a unifying historical narrative for East and West Pakistan.28 However, being an Islamic nation, Pakistan rarely recalls its Buddhist heritage. During the visit to Sri Lanka, Khan agreed to open the pilgrimage corridors for Sri Lankans to visit ancient Buddhist heritage sites in Pakistan.29

This is not the first time Pakistan has used its Buddhist legacy to advance its foreign relations. Following India’s bid to invoke Buddhism in its outreach to some of its neighbours, Pakistan has been seen to be using its Buddhist heritage in its ties with Sri Lanka and Nepal in recent years. In 2019, it sent sacred relics of Gautama Buddha to Sri Lanka on the occasion of the Vesak festival in the island nation.30 This is the first time, however, that Pakistan has openly offered to facilitate Buddhist pilgrimage for Sri Lankans. While this will boost tourism for both countries, it will also enhance people-to-people partnerships.

Another key highlight was Khan’s discussions with Muslim parliamentarians. Even though the meeting was first cancelled citing security concerns,31 it was later held with the participation of 15 Muslim members of parliament (MPs) across political parties.32 MP Rauf Hakeem was quoted for describing the meeting as “fruitful” and saying that Khan expressed his confidence in the island nation’s leadership to improve harmony among all Sri Lankans.33 The meeting was significant for the Sri Lankan Muslim community as well as the Rajapaksa government’s relations with the Islamic world.

It was held amidst an on-going controversy in Sri Lanka with regard to Muslim burial rights for COVID-19 related deaths. Despite the World Health Organization’s recommendations and the medical experts’ reiteration that there is no public health hazard rationale to cremate the bodies,34 Sri Lanka did not allow these bodies to be buried. The human rights group, Human Rights Watch, has widely criticised this act across the globe.35 Ahead of Khan’s visit, requests were made by Sri Lankan Muslims and international rights groups to raise the matter of forced cremations with Sri Lankan authorities.36 However, press releases issued by both countries did not mention Khan raising this with his Sri Lankan counterparts.37 Thus, critics emphasised that the visit could not win Pakistan’s foreign policy anything beyond a ceremonial welcome, and any effort on Pakistan’s part “were quietly snubbed by Sri Lanka”.38 However, the announcement that came just two days after Khan’s visit on revoking the decision to ban COVID-19 burials discredited these criticisms.39

As Sri Lanka prepared to face a UNHRC resolution in March 2021, it alienated a number of Muslim countries due to the abovementioned burial issue. It was also being criticised for its deteriorating human rights; hence, it needed the support of every possible country internationally. Past experiences have shown Pakistan to be a lynchpin in consolidating the OIC member countries’ support in favour of Sri Lanka.

Reflections

The two-day visit attracted a fair amount of controversy due to the cancellation of Khan’s invitation to address the Sri Lankan parliament. The announcement which came just a couple of days prior to the visit was viewed as Colombo’s attempt to avoid confrontation with India.40 Thus, the cancellation of the parliamentary address and the Muslim MPs’ meeting were viewed as an act to prevent raising the forced cremation issue.41 However, the visit proved that ties between Colombo and Islamabad are on a much more solid footing than immediately apparent; and that it is unlikely to become a sticking point in a long and steady relationship.

Sri Lanka gave a grand ceremonial welcome with much fanfare to Khan upon his arrival in Colombo. Mahinda went on to recall how Pakistan is held in high esteem for its unwavering support to Sri Lanka during its fight against terrorism and emphasised that, “Pakistan was a friend who stood by and helped Sri Lanka in times of great need. We are grateful for the steadfast support.”42 Sri Lanka showed a special documentary which recalled Khan’s cricket legacy during the inauguration of the High-Performance Sports Complex. The video included Khan’s contemporary Sri Lankan cricketers recalling his visionary leadership during his cricketing career. The News on Sunday reported that Khan was showered with nothing but respect and honour during the visit.43 If the previous controversies were to affect the visit, this gesture ironed out the situation.

However, the abrupt actions and decisions which caused these controversies require deep reflection on Sri Lanka’s part. Khan made the visit to Sri Lanka when an invitation was already being extended to Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi to make the first state visit to Colombo under the current administration. The former’s visit also followed a straining of relations between Sri Lanka and India on account of the East Container Terminal issue and multiple power projects with Chinese involvement. Thus, Sri Lanka could have deeply considered these factors before extending an invitation to a Pakistani leader at a critical time.

Sri Lanka could have also considered the possibility of Khan raising the Kashmir question at Sri Lanka’s parliament before inviting him to make an address in the first place. The Kashmir issue is Pakistan’s single sovereignty issue in the South Asian region. This has led to not only its strained relations with India, but has also effectively prevented any possible progress in regional organisations such as the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC). In 2019, the Indian government under Modi curtailed the semi-autonomous status of Kashmir by revoking Article 370 of the Indian constitution, changing the dynamic in Kashmir.44 To date, the South Asian region remains the least integrated due to India and Pakistan’s issues. Thus, a visiting head of state of Pakistan raising the Kashmir question in another South Asian country is inevitable. Thus, cancelling a planned address suggests that Sri Lanka’s foreign policy decisions lack careful thought or planning and suggest indecisiveness and Sri Lankan foreign policy’s vicissitudes.

The cancellation being viewed as a reaction to India’s concern gives an incorrigible impression that Sri Lanka is willing to succumb to Indian pressure even at the expense of its relations with friends. In the words of the Sri Lankan leaders, Pakistan has been an unwavering friend to the island nation even at difficult times. Pakistan’s strong supportive statement at the voting on the UNHRC resolution and its vote in favour of Sri Lanka on 23 March 2021 proved Pakistan to be an all-weather friend of the island state. Hence, if the decision to cancel the parliamentary address was in consideration of India’s sensitivities, it raises questions about Sri Lanka’s sincerity with regards to relations with its strong and steadfast friends.

In fact, this is not the first time Sri Lanka has backed down from reciprocating with Pakistan due to Indian sensitivities. In 2016, the 19th SAARC summit, which was initially planned for Islamabad, was cancelled due to Indian protests after an attack on an Indian army camp in Kashmir. Sri Lanka followed through.45 Colombo insisted on not backing out of the summit and said that it only expressed regret that the region’s prevailing environment was not conducive to hold the event 46 and later promised to support Pakistan’s bid to host the next.47 However, the decision already established an impression of Sri Lanka supporting India’s alleged claims against Pakistan.

Pakistan is not just Sri Lanka’s steadfast friend in South Asia, but also its gateway to Colombo’s outreach to Central Asia and the Muslim world. Pakistan, being part of China’s Belt and Road Initiative, is opening up connectivity to the Central Asian region via the CPEC. As Sri Lanka is looking ahead to diversify its economic connectivity, Pakistan can be a gateway to the Central Asian subcontinent. In fact, Khan brought up the CPEC during his discussions with Sri Lankan authorities and expressed interest in exploring possibilities to enhance Pakistan’s trade and connectivity with Sri Lanka, and through the CPEC, right up to Central Asia for Sri Lanka. This is an opportunity for Colombo as its current trade is only centred mainly in Europe and South and East Asia.

Pakistan also provides an opportunity for Sri Lanka to strengthen its relations with the OIC member countries. The OIC member states have proven to be a strong support group for Sri Lanka in the past during its contentious relations with the West and its allies. Recent years have complicated Sri Lanka’s ties with the Muslim world due to the recent Islamic extremist terror attack which has resulted in rising ethnic polarisation. Thus, Sri Lanka can raise its case and concerns with the Muslim world via its connections with Pakistan.

Finally, Sri Lanka should reflect upon its decisions in the context of its pledge to follow a neutral foreign policy. Neutral foreign policy should not apply only in its dealings with the great powers amidst their rivalry. It should be the policy in dealing with every country. If Sri Lanka comes across to be favouring one over another at any given circumstance, its bid to be a neutral player in the Indian Ocean will be questioned.

. . . . .

Dr Chulanee Attanayake is a Visiting Research Fellow at the Institute of South Asian Studies (ISAS), an autonomous research institute at the National University of Singapore (NUS). She can be contacted at chulanee@nus.edu.sg. The author bears full responsibility for the facts cited and opinions expressed in this paper.

Photo credit: Twitter/Mahinda Rajapaksa.

-

More From :

More From :

-

Tags :

Tags :

-

Download PDF

Download PDF