Summary

Pakistan’s Prime Minister, Imran Khan, arrived in Kuala Lumpur on 3 February 2020 on his second state visit to Malaysia. This paper analyses the economic and geopolitical developments behind this state visit.

On 3 February 2020, the Prime Minister of Pakistan, Imran Khan, arrived in Kuala Lumpur on a two-day visit. The visit aimed at reaffirming Malaysia’s and Pakistan’s commitment to strengthening economic, strategic and security relations.

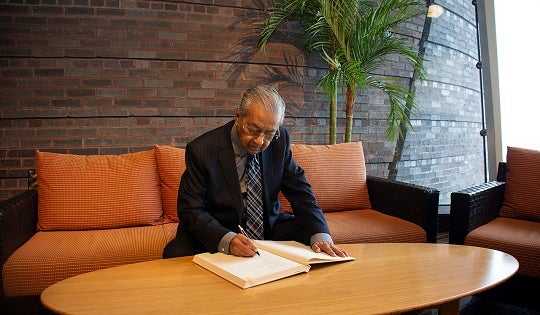

While Malaysia and Pakistan have generally enjoyed cordial diplomatic relations, Khan and his Malaysian counterpart, Mahathir Mohammad, have sought to cultivate firmer ties between the countries. In March 2019, Mahathir was the Guest-of-Honour at the Pakistan Day celebrations in Islamabad and was conferred Pakistan’s highest civilian award, the Nishan-e-Pakistan. During this visit, both leaders signed memorandums of understanding worth an estimated US$900 million (S$1.39 billion). Mahathir also laid the foundation stone for Proton’s first South Asian assembly plant. Located near Karachi, this plant is expected to begin operations in June 2020. In the past year, both leaders have articulated their desire to corporate to challenge the problem of Islamophobia and for their countries to “collaborate more closely on issues affecting Muslims”. Khan has also expressed his gratitude for the fact that Mahathir had raised concerns over the conditions of Muslims in Indian Kashmir.

The relations between the countries were, however, tested when Khan pulled out of the Kuala Lumpur Summit. Hosted by Malaysia on 19-21 December 2019, this summit was planned as a gathering of Muslim countries to discuss challenges confronting Muslim states. Khan missed the summit because of pressure from the Saudis who saw this as an attempt to challenge the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation. Thus, this state visit was an attempt to reaffirm Pakistan’s commitment to its ties with Malaysia. It was also motivated by pressing economic and geopolitical developments. The importance of Pakistan-Malaysia relations is reflected in the fact that this was Khan’s second visit to Malaysia since coming to power in 2018. On its part, Malaysia views Pakistan as a market and a means of accessing the economies of Central and Western Asia.

In the immediate term, Malaysia is hoping to expand its exports of palm oil to Pakistan. Malaysia is grappling with the effects of restrictions imposed by India upon the import of palm oil from Malaysia. India, the world’s largest importer of palm oil, allegedly placed these restrictions in response to Mahathir’s comments on Kashmir. In the longer term, Malaysia is anticipating a drastic drop in the demand for palm oil as the European Union bans the use of palm oil. As the competition for markets for palm oil between Malaysia and Indonesia intensifies, Malaysia is looking to Pakistan. Malaysia’s Minister of Primary Industries, Theresa Kok, stated that while Pakistan currently imports 22 per cent of its crude oil from Malaysia, she hopes that this figure rises to 50 or 60 per cent. In 2007, Pakistan reduced tariffs on Malaysian palm oil by 10 per cent, thereby benefitting Malaysia. However, Malaysia’s dominance in the sector was challenged when the same tariff reduction was offered to Indonesia in 2013. Given that crude palm oil from Indonesia is cheaper, Indonesia emerged as the largest supplier of palm oil to Pakistan. Khan has assured Malaysia that Pakistan will make up for the shortfall caused by the Indian restrictions. Nonetheless, it is fair to surmise that Pakistan would want to purchase palm oil at lower rates. Khan’s visit ushers in the beginning of discussions on issues such as price and tariffs relating to palm oil.

More broadly, both leaders reaffirmed their commitment to the Malaysia-Pakistan Closer Economic Partnership Agreement (MPCEPA). Signed in 2007, it covers trade in goods and services, investments and economic cooperation. This was the first free trade agreement between Malaysia and a South Asian country and remains one of the most comprehensive agreements Pakistan has signed. Over the years, Pakistan’s exports to Malaysia have diversified from agricultural goods to manufactured goods such as aluminum and multi-range iodine. Pakistan business groups are hoping that the MPCEPA will allow them access to Malaysia and, through Malaysia, the markets of Southeast Asia. In their discussions, both leaders agreed to expand the scope of the MPCEPA to focus on sectors like renewable energy, aerospace and heavy industries.

It is no coincidence that Khan’s visit took pace two weeks before the meeting of the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) in Paris. The FATF, which monitors money laundering and terrorist financing, has placed Pakistan on its ‘Grey List’. It is estimated that Pakistan has lost US$6 billion (SG$8.3 billion) worth of investments annually as a result of this. Support from Malaysia in the upcoming FATF meeting is critical for Pakistan. Malaysia had previously played an important role in ensuring that Pakistan was not placed in the FATF’s ‘Black List’. The fact that Khan received Malaysia’s backing is reflected in the joint-statement issued by both leaders which stated that Malaysia acknowledged the extensive counter-terrorism efforts made by Pakistan and the progress made in complying with FATF’s recommendations.

Overall, Khan’s visit builds on economic initiatives launched during Mahathir’s trip to Pakistan in 2019. It is worth noting that both sides have stated that they will now lay the groundwork for the fourth Joint Committee Meeting of the MPCEPA to be held in Islamabad. The visit also reflects the increasing strategic and geopolitical importance of bilateral relations between Malaysia and Pakistan.

Associate Professor Iqbal Singh Sevea is a Visiting Research Associate Professor at the Institute of South Asian Studies (ISAS), an autonomous research institute at the National University of Singapore (NUS). He can be contacted at iqbal@nus.edu.sg. The author bears full responsibility for the facts cited and opinions expressed in this paper.

-

More From :

More From :

-

Tags :

Tags :

-

Download PDF

Download PDF