Nutritional Consequence of the Lockdown in India: Indications from the World Bank’s Rural Shock Survey

Divya Murali, Diego Maiorano

6 April 2021Summary

This paper analyses the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the consumption of rural households in India through evidence from World Bank’s COVID-19-Related Shocks in Rural India 2020. The analysis shows that a sizeable section of the rural population had to compromise on their food intake, reflecting widespread vulnerability to economic shocks.

Introduction

In April 2021, India experienced a second wave of COVID-19 infections, after having seen the number of cases dramatically decline between September 2020 and February 2021. With the effects of the pandemic still unfolding, this research looks at the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic – in particular of the lockdown enacted from March 2020 to May 2020 – and the resulting nutritional consequences on the country’s rural population using World Bank’s ‘COVID-19-Related Shocks in Rural India 2020’ survey.1 For this study, we consider consumption related data from Round 3 of the survey which was carried out between 20 and 24 September 2020 and includes 1,460 rural households across the six states of Andhra Pradesh, Bihar, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh.

This paper is organised into the following sections: lockdown in India, economic, social and nutritional consequences of the lockdown, results from the COVID-19 shock survey, relief measures and conclusion.

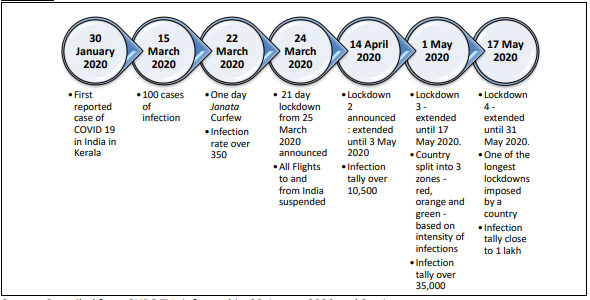

The Lockdown

On 30 January 2020, India reported its first case of COVID-19 infection in the state of Kerala. Things were under control until 15 March 2020 when the number of country-wide infections hit 100. By 20 March 2020, the number of cases was close to 250. 2 With the numbers escalating and limited testing capabilities, on 22 March 2020, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi called for a 24-hour janata (public) curfew. Then, on 24 March 2020, with a notice of just four hours, the government imposed a 21-day nationwide lockdown and all flights (international and domestic) to and from India were suspended.

Figure 1: Lockdown timeline

Source: Compiled from CNBC TVs infographic, 23 August 2020 and Statista.

https://www.cnbctv18.com/photos/healthcare/coronavirus-india-timeline-from-first-covid-19-case-in-keralato-over-3-million-cases-today-6708401-6.htm ; https://www.statista.com/statistics/1104054/indiacoronavirus-covid-19-daily-confirmed-recovered-death-cases/ .

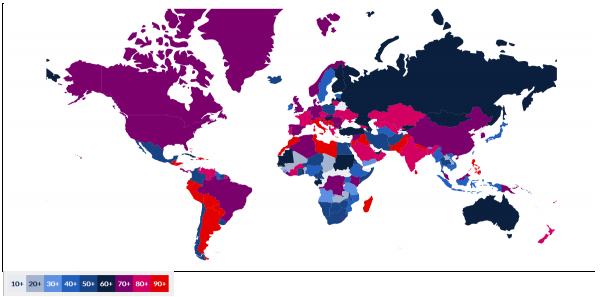

The lockdown imposed the shutdown of all commercial, industrial and transport activities and was extended several times. Eventually, restrictions started to ease on 8 June 20203 when the first of many “Unlocks” began. According to the Stringency Index developed by Oxford University, India’s lockdown was one of the harshest in the world (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Oxford COVID-19 government response stringency index – Lockdowns around the world

Source: Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker for the period between 24 March 2020 and 31 May

2020. https://covidtracker.bsg.ox.ac.uk/stringency-map .

With all non-essential activities and transportation suspended, millions of migrant workers from cities across India suddenly found themselves without any source of income and shelter. Many started the long journey back to their villages, often on foot. This exodus is believed to be one of the most significant factors which spread the virus into the rural areas.4 As a result, the country’s economic, welfare and social security has been under stress.

Economic, Social and Nutritional Consequences of the Lockdown

Employment, income level and nutrition have a very close link in developmental perspective as they feed into each other and affect the consumption levels in the country. According to the International Labour Organization, over 90 per cent5 of the India’s entire workforce is informally employed.6 The proportion of informal employment in non-agricultural employment is over 80 per cent and the percentage of people in vulnerable employment7 (of total employment) is nearly 75 per cent.8 These high numbers show that a large proportion of the Indian workforce was highly vulnerable to economic shocks, even before the pandemic hit.

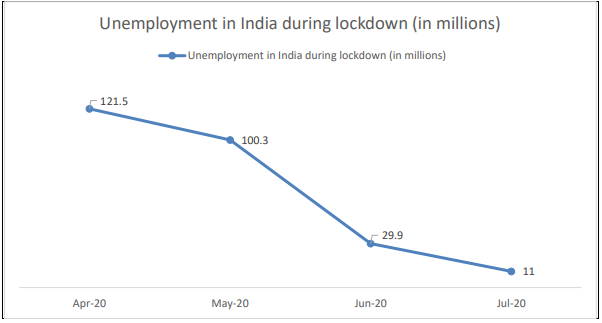

The 68-day long lockdown in India further afflicted people’s livelihoods. As economic activity suffered, it resulted in a sharp contraction of employment. According to Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE) Household Pyramid Survey, cumulative job loss from April to July 2020 was at 11 million. In April 2020, when the job loss was at 121.5 million, 75 per cent9 of those were among people in the informal sectors like small traders, hawkers and daily wage labourers.

Although the situation improved significantly with the subsequent easing of the lockdown, this is evidence enough to show how highly vulnerable this segment of the population is and how transient their nature of employment is. Given the very low savings capacity of the large majority of the population, 10 from the unemployment data for the months of April and May 2020, it can be inferred that millions went through a phase of high financial (and possibly food) insecurity. There also seems to have been a shift from high-productivity jobs in the manufacturing and service sector to low productivity ones like agriculture and construction. This might translate into lower incomes for a sizeable section of the population, also considering the sharp contraction of informal workers’ real wages during the first two lockdown (-22.6 per cent).11

Figure 3: Unemployment in India during the lockdown (in millions)

Source: CMIE, Household Pyramid Survey

Lower income means lower purchasing power leading to restrained/limited access to food. This translates to compromised nutrition intake and is a vicious cycle which ultimately affects the country’s human capital. Nutrition, as such, has always been a big cause of concern in India. According to the Global Hunger Index 2020, 12 India ranked 94 (out of 107 countries in the index), indicating a “serious” nutritional situation. With loss in real wages owing to the pandemic, consumption levels of people will directly be affected thereby exacerbating the already poor nutrition status of the country which could have severe longterm implications.

Results from the COVID-19 Shock Survey

In the COVID-19 Rural Shock Survey conducted by the World Bank across six states, the average per capita consumption by a household in any given month during lockdown was ₹1,210 (S$22.44). Thirty seven per cent of the sampled households ran into situations where, owing to the lack of money or other resources, they had to a) reduce portion sizes; b) ran out of food; c) someone in the household was hungry but did not eat; and/or d) someone in the household went without eating. Further, 25 per cent of the households responded that they had to specifically reduce portion sizes during the lockdown months. This share was higher in Andhra Pradesh and Bihar at 29 per cent and 38 per cent respectively.

This finding is worrying as it shows that one in three households in the rural areas had compromised on its food intake in one form or the other. The average household size of the survey is around six. What this means is that in any village which one randomly picks in any of these surveyed states, every third house’s consumption intake is likely to have been directly impacted by the lockdown. A household is likely to consist of members in varying age groups. Given that a household’s consumption was forced to be compromised, this directly affects nutrition intake and thereby affects its immunity negatively. For children, there is a plethora of research which says that it directly impacts their cognitive skills and immunity. With pregnant or lactating mothers, under-nourishment not only directly impacts the baby or the infant’s development but it can also threaten the pregnancy itself. With middle-aged working people, the lack of nutrients and insufficient food intake leads to fatigue which lowers productivity. With elderly, it could lead to several health concerns.

A closer inspection across the six states in the survey shows that 50 per cent of the households in Bihar and 39 per cent of households in Uttar Pradesh ran into situations where their consumption was compromised due to the lack of money or other resources. It is interesting to note that these states are traditionally considered backward in terms of both growth and development. These are also the states from which most migrant workers come from. Both of this point to households having to not only deal with lowered incomes due to job losses but had to also split the little income among expanded households owing to the return of migrant workers.

The survey was done mid-September 2020, four months since the “Unlocks” began. A follow-up question on how the household consumption has changed in the previous seven days shows that 23 per cent of the households still responded that they ran into situations where their consumption had to be compromised. Particularly, 12 per cent of the total households responded that they had to reduce food portion in the last seven days. In four out of the six surveyed states, this figure was over 10 per cent which suggests to a widespread problem. The numbers were 20 per cent in Bihar, 11 per cent in Andhra Pradesh and 10 per cent in Madhya Pradesh as well as Uttar Pradesh.

While the CMIE employment data showed that unemployment reverted to almost prepandemic levels by July 2020, 13 the fact that still nearly a quarter of the households had to compromise on consumption points to significant levels of food insecurity over the medium term and is concerning.

Relief Measures and Discussion

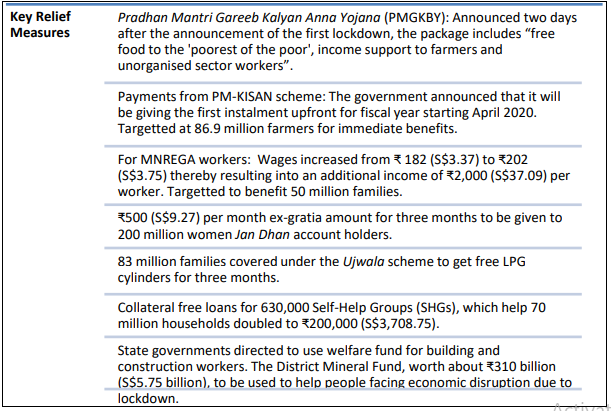

With the pandemic posing serious challenges, the Indian government enacted a series of relief measures to tackle to the situation. Some of these are given in Table 1.

Source: Compiled from ‘India: Government and institution measures in response to COVID 19’, KPMG Insights, updated on 2 December 2020. https://home.kpmg/xx/en/home/insights/2020/04/india-government-andinstitution-measures-in-response-to-covid.html ; Abhishek De, ‘Coronavirus India timeline: Tracking crucial moments of Covid-19 pandemic in the country’ The Indian Express, updated 1 October 2021. https://indianexpress.com/article/india/coronavirus-covid-19-pandemic-india-timeline-6596832/ .

When the government announced the support of additional five kilogrammes of wheat and one kilogramme of pulses under PMGKBY scheme, it was done so only until November 2020 and was not further extended.14 According to reports, India’s buffer food grain stocks as of 1 January 2021 were 2.7 times more than the required buffer stock level.15 Given the context and the strain of the pandemic on household consumption, the government could have easily extended the scheme or made it universal, which did not happen.

Furthermore, the great majority of the schools and childcare (anganwadi) centres remain closed at the time of writing in April 2021. Since these centres provide meals to millions of children and lactating mothers, the reduced food intake could also be a consequence of the decision not to reopen schools and anganwadi centres, while allowing most other economic activities to resume.

More generally, the relief package is largely thought to be insufficient, as evidence from the World Bank survey show. Overall, actual new spending announced by the Finance Minister ranged somewhere between ₹400 billion to ₹500 billion (S$7.42 billion to S$9.27 billion), almost all allocated to the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act. 16 The total actual economic package was worth about 1.2 per cent of the gross domestic product, well short of the announced 10 per cent.17

Conclusion

The lockdown imposed on 24 March 2020 extracted a significant toll on the rural population. With all economic activities coming to a halt, unemployment soared and many families had to compromise on their food intake to face the situation. This built upon high levels of food and economic insecurity even before the pandemic hit India. The relief measures put in place by the government, while effective in avoiding a situation of mass starvation, came short of ensuring enough means for a large proportion of the rural households to avoid reducing the amount of food they were able to consume.

. . . . .

Ms Divya Murali is a Research Analyst at the Institute of South Asian Studies (ISAS), an autonomous research institute at the National University of Singapore (NUS). She can be contacted at divya.m@nus.edu.sg. Dr Diego Maiorano is a Research Fellow at the same institute. He can be contacted at dmaiorano@nus.edu.sg. The authors bear full responsibility for the facts cited and opinions expressed in this paper.

Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons.

-

More From :

More From :

-

Tags :

Tags :

-

Download PDF

Download PDF