New Directions and Challenges of the Trump 2.0 Indo-Pacific Strategy

Bian Sai, Mriganika Singh Tanwar

16 July 2025Summary

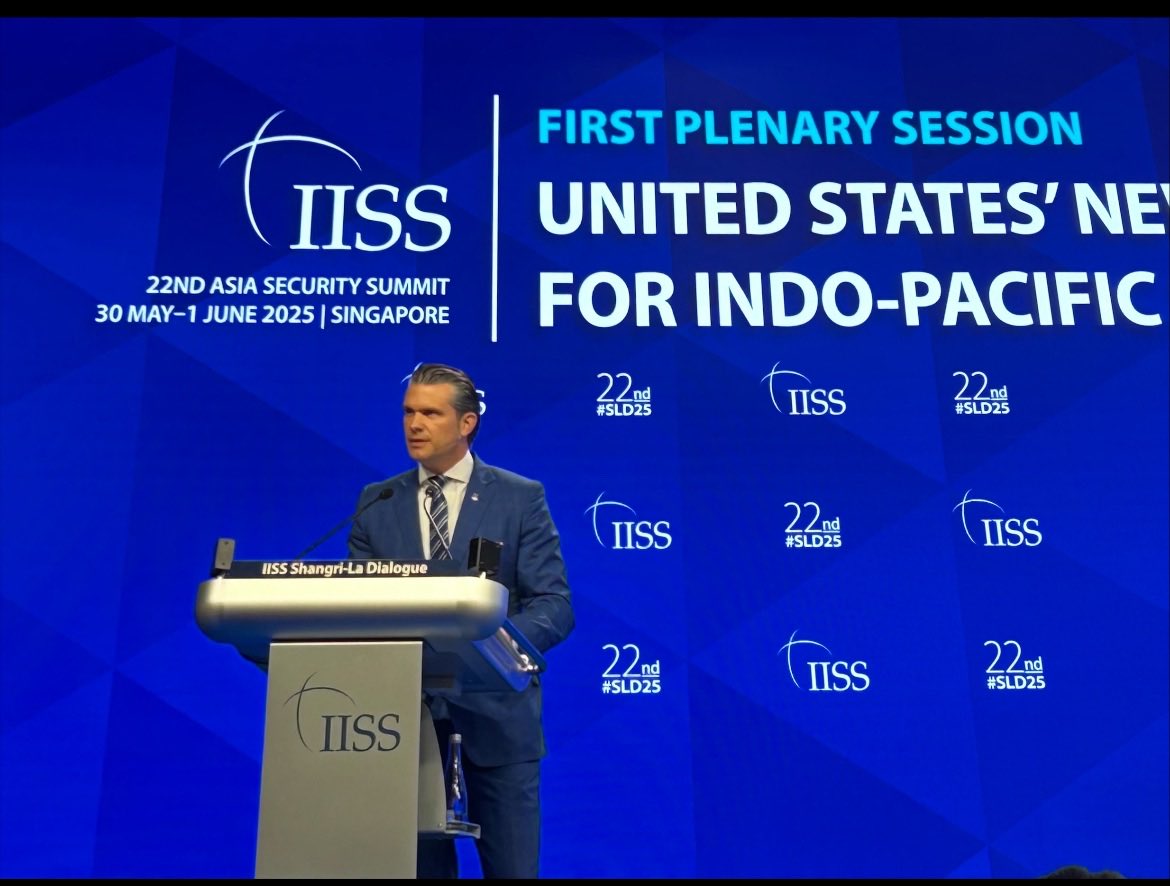

On 31 May 2025, United States (US) Defence Secretary Pete Hegseth delivered a keynote address at the Shangri-La Dialogue in Singapore, outlining the Trump 2.0 vision for the Indo-Pacific region. During his speech, he explicitly identified China as the primary threat facing the US in the region and proposed corresponding policy responses. Compared to the Indo-Pacific strategy during Trump’s first term that underlined a rules-based order, several new features are evident in the Trump 2.0 ‘peace through strength’ approach. The strategy faces significant challenges that threaten to undermine the US influence.

Departure from Ideological Preaching

The ‘Free and Open Indo-Pacific’ strategy of United States (US) Donald Trump’s first term was heavily infused with ideological overtones. It sought to portray strategic competition between the US and China in the region as a confrontation between freedom versus repression and openness versus closedness. As part of the Trump administration’s National Security Strategy 2017, the US’ Strategic Framework for the Indo-Pacific was influenced by Washington’s approach to countering Beijing’s economic and political influence.

In contrast, US Defence Secretary Pete Hegseth’s keynote address at the Shangri-La Dialogue in Singapore on 31 May 2025 emphasised that the Trump administration would refrain from lecturing allies and partner states on political or ideological grounds. Even though China was outlined as the primary threat, he clarified the US’ intentions of prioritising cooperation grounded in ‘mutual interests and common sense’ to safeguard peace and protect economic ties.

Aversion to Foreign Aid Spending

Hegseth’s speech reflected the Trump 2.0 administration’s more unabashed embrace of the ‘America First’ doctrine. It not only drastically downsized the US Agency for International Development (USAID) but also announced a 90-day freeze on all foreign aid.

In its proposed fiscal year (FY) 2026 budget, the Trump administration intends to issue steep cuts to the State Department budget by US$30 billion (S$40.8 billion), leading to the shutdown of 30 American missions and slashing foreign aid by nearly 75 per cent. The total proposed budget for FY2026 stands at approximately US$1.7 trillion (S$2.31 trillion), representing a 7.6 per cent reduction from US$1.83 trillion (S$2.48 trillion) allocated for FY2025. According to the budget outline released by the White House, non-defence discretionary spending will be cut by US$163 billion (S$221.6 billion), marking a 22.6 per cent decrease from current levels. Specifically, the budget proposes reductions across various sectors, including education, housing, medical research, foreign aid, energy, and environmental protection, amounting to a total of US$163 billion (S$221.6 billion) in spending cuts, while simultaneously seeking to raise defence spending to over US$1 trillion (S$1.36 trillion). Allocations for diplomacy and development are slated for a US$49.1 billion (S$66.78 billion) cut, the lowest level in nearly eight decades. Additionally, the US’ foreign aid allocations to the Southeast Asian countries in 2025 have been dramatically reduced across the board compared to 2024, with most countries experiencing funding cuts exceeding 90 per cent.

Table 1: Reduction in US Foreign Aid in Southeast Asia (2024-2025)

| Country | Total Allocation in 2024 (US$) | Total Allocation in 2025 (US$) | Change (US$) | Percentage Change (%) |

| Myanmar | 247,425,052 | 8,553,600 | -238,871,452 | -96.54% |

| Indonesia | 794,707,052 | 47,603,213 | -747,103,839 | -94.01% |

| Vietnam | 303,576,725 | 21,259,485 | -282,317,240 | -92.99% |

| Thailand | 48,092,057 | 8,759,159 | -39,332,898 | -81.78% |

| Malaysia | 6,207,234 | 13,009 | -6,194,225 | -99.79% |

| Philippines | 719,665,921 | 41,622,154 | -678,043,767 | -94.22% |

| Cambodia | 143,935,605 | 24,860,517 | -119,075,088 | -82.74% |

| Laos | 162,911,205 | 6,838,610 | -156,072,595 | -95.80% |

Source: The US Department of State (n.d.). Foreign Assistance Data.

Increase in Defence Spending and Allied Burden-Sharing

Although the Trump administration, during its first term, also pressed the Indo-Pacific allies to increase defence expenditure, the focus had previously been on compelling Japan and South Korea to shoulder a greater share of the costs for hosting US troops. However, Trump 2.0 has adopted a broader approach, advancing allied burden-sharing across three dimensions. First, it is urging its military allies such as Japan and South Korea to raise their defence budgets to 3.5 per cent of their respective gross domestic products. Second, the administration seeks to enhance military interoperability through frequent joint exercises and training programmes, aimed at improving collective operational capabilities. Third, it also emphasises deeper collaboration with other countries like Australia and India in defence technology transfer, weapons research and development, production, maintenance and logistical support. This approach aims to increase the overall defence capability and industrial bases, particularly in the production of warships, aircraft, missiles and munitions, to address the shortfalls of the US domestic defence manufacturing base.

Regardless of Hegseth’s declaration of a continued US presence in the region through its renewed Indo-Pacific strategy, several practical challenges remain unaddressed by the current administration. On the one hand, the Trump administration’s emphasis on ‘America First’ has caused unease even among Washington’s closest allies. Japan and Australia, traditionally the most steadfast US allies in the Indo-Pacific, have expressed dissatisfaction with the Trump administration’s perceived ‘burden-shifting’ in security and heavy-handed economic demands. The Trump administration’s economic pressure tactics of reciprocal tariffs sent a shockwave across Southeast Asian counterparts. On the other hand, many countries in Southeast Asia and the South Pacific have long hoped for increased US assistance. US Secretary of State Marco Rubio announced via the social media platform X that USAID would eliminate 5,200 out of its 6,200 global programmes, claiming the move would cut ‘tens of billions of dollars’ in spending, deemed harmful to the US’ national interests.

In sum, the evolution of the Indo-Pacific Strategy bears a distinct Trumpian imprint. How it will develop in the future remains to be seen.

. . . . .

Ms Bian Sai is an Academic Visitor at the Institute of South Asian Studies (ISAS), an autonomous research institute at the National University of Singapore (NUS). She can be contacted at isav34@partner.nus.edu.sg. Ms Mriganika Singh Tanwar is a Research Analyst at the same institute. She can be contacted at m.tanwar@nus.edu.sg. The authors bear full responsibility for the facts cited and opinions expressed in this paper.

Pic Credit: X

-

More From :

More From :

-

Tags :

Tags :

-

Download PDF

Download PDF