Summary

West Bengal heads to the polls in end-March 2021. Opinion polls have predicted a tight race with the ruling Trinamool Congress having an edge over the Bharatiya Janata Party. Irrespective of the results in West Bengal, the foregrounding of identity politics is likely to change the ground rules of politics in the state.

Introduction

Of the four states and one union territory that head to polls in end-March 2021, West Bengal has received the most attention. There are a few reasons for this.

One, West Bengal Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee has been the most vocal critic of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) regime since Prime Minister Narendra Modi was voted to power in 2014. The Modi regime has turned the West Bengal election into a prestige battle with the BJP pouring in enormous amount of resources, both by way of money and leadership. Indeed, the Election Commission has stretched out the West Bengal election to an unprecedented eight phases running over a month from 27 March to 29 April 2021, even as Tamil Nadu and Kerala have one day polls, over fears of violence. This is likely to maximise the impact of Modi and the BJP central leadership on the poll campaign.

Two, West Bengal, which sends 42 members of parliament (MPs) to the Lok Sabha (Lower House), has traditionally been lukewarm to the BJP. However, over the last few years, it has turned more favourable towards the party. In the 2019 general election, the BJP’s seat tally increased dramatically from two to 18. It hopes to capitalise on the momentum to wrest away control of a state that has never had a BJP government. Besides, this is the first time that the dominant regional party in Bengal is facing a real challenge from the ruling party at the centre.

Three, of all the state elections, West Bengal is likely to be the closest. Opinion polls have predicted a tight race with the ruling Trinamool Congress (TMC) currently ahead. The latest such poll by ABP CVoter found that the TMC is likely to win 43 per cent of the vote share, similar to what it won in 2019, while the BJP’s vote share is likely to slip marginally from 2019 to around 38 per cent. This would translate to 150-166 seats for the TMC, a slim majority in the Assembly, compared to 98-114 seats for the BJP. The Left, which has allied with the Congress, is predicted to be a distant third with 13 per cent of the vote share and between 23-31 seats.1

The Bjp’s Rise

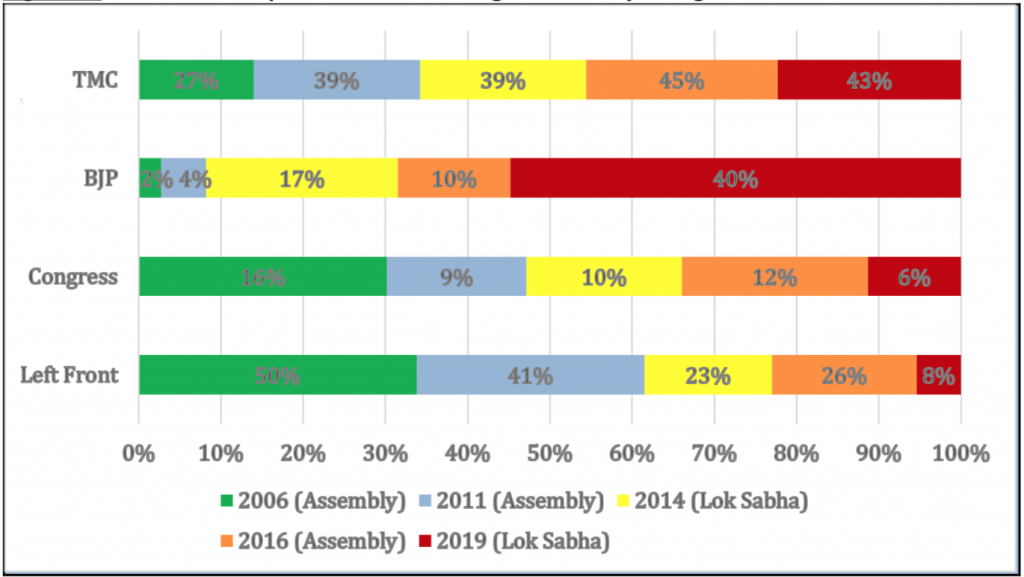

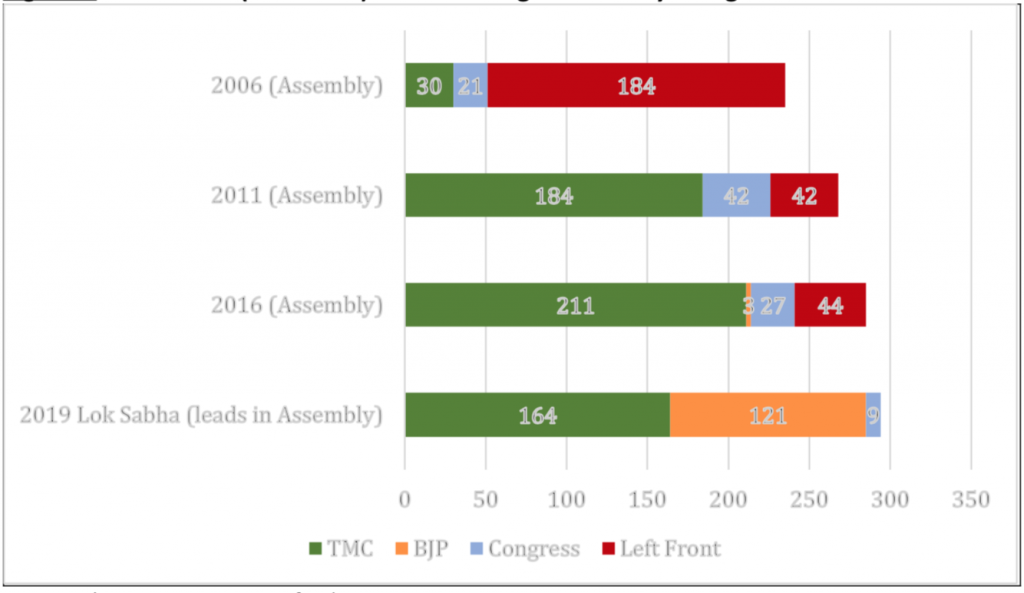

The BJP had won only three seats in the 2016 Assembly election with 10 per cent of the vote share. In sharp contrast, in the 2019 general election, it not only won 18 seats but its vote share went up to 40 per cent, only three percentage points behind TMC (Figures 1 and 2). Part of the increase could be ascribed to the Modi effect which usually gives the BJP a bounce during general elections. But the increase was more due to the transfer of a bulk of the vote for the Left Front and Congress to the BJP. The combined vote share of the Left and the Congress fell from 39 per cent in the 2014 general election to a mere 13 per cent in 2019. In the past five years, the BJP has been the principal beneficiary of the decline of the Left Front, which had governed West Bengal for 34 years. According to Lokniti-CSDS data, in 2019, around two-fifths of the traditional Left voters voted for BJP while a third switched to TMC.2

Figure 1: Vote share of parties in West Bengal assembly and general election

Source: Election Commission of India

The BJP’s rise has been founded on two other factors: religious polarisation and anti- incumbency sentiments. Initially, the BJP’s attempts at polarisation were based on the perception that the TMC and Mamata were appeasing the Muslims, who constitute 27 per cent of the state’s population, going by the 2011 Census. Since 2014, however, the BJP has consciously attempted to consolidate the Hindu vote in West Bengal where identity politics have traditionally not been so prominent. One of the ways the BJP has done so is by popularising Hindu festivals like Ram Navami and the use of the ‘Jai Shri Ram’ slogan, both of which were alien to West Bengal, and using it also for caste mobilisation.

Figure 2: Seat share (and leads) in West Bengal assembly and general election

Source: Election Commission of India

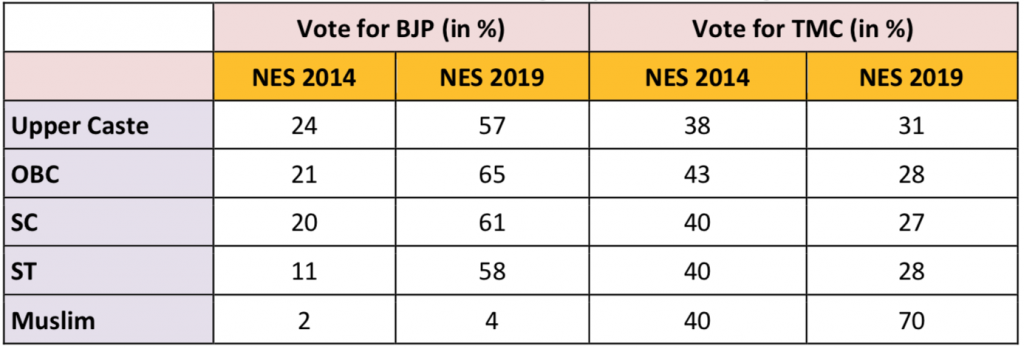

Mamata had tried to counter it with measures like allowances for Hindu priests and funds for community Durga Pujas. The BJP strategy has paid off particularly with regard to the Scheduled Castes (SCs) and Scheduled Tribes (STs), a phenomenon that has been termed “subaltern Hindutva” by some analysts. The SCs comprise nearly a quarter of West Bengal’s population while the STs are at six per cent. This section has been marginalised in Bengal politics where the upper castes have dominated. The BJP has also actively wooed the Other Backward Classes (OBCs) and given it a communal twist. It has alleged that the TMC has granted the OBCs benefits disproportionately to the Muslims and has promised more reservations for Hindu OBC groups.3 The caste outreach is important since Muslim voters rarely vote for the BJP.

What started with the BJP actively wooing SCs like Rajbanshis and Namasudras in 2014 has expanded to cover lower castes across the state. The swing of lower caste voters towards the BJP has been confirmed by ethnographic accounts.4 According to Lokniti-CSDS data, nearly 60 per cent of the lower castes voted for the BJP in 2019, up from 20 per cent in 2014, and a similar proportion of STs preferred the BJP in 2019 against 11 per cent in 2014 (Table 1).5 Indeed, in constituencies with a higher proportion of SCs and STs, the vote share of the BJP went up significantly.6 The BJP in 2019 also won five of the 10 Lok Sabha seats reserved for SCs and both seats reserved for STs in West Bengal.

Table 1: Vote share of TMC and BJP in West Bengal by caste and religion

Source: Lokniti-CSDS

The BJP has also benefitted from anti-incumbency sentiments against the TMC, which is seeking a third term in government.7 This is captured in the BJP’s slogan of poriborton or change, which was once associated with TMC when it ousted the Left Front in 2011. The BJP has in particular exploited the anger of voters against petty corruption – the so-called ‘cut money’ or extortion by TMC members – and the violence by TMC cadre, which was most dramatically on display in the 2018 panchayat election. This has undermined the development work and social welfare programmes of the TMC.

A third factor that could aid the BJP is the newly formed Indian Secular Front, formed by Muslim cleric Abbas Siddiqui, which has tied up with the Left and Congress for the coming election. Siddiqui is associated with the popular Sufi shrine, Furfura Sharif, with which Mamata had earlier built close links. The shrine is also located in south Bengal, which is the TMC’s stronghold. Siddiqui’s entry into politics has dealt a blow to the ambition of Asaduddin Owaisi’s All India Majlis-e-Ittehad-ul-Muslimeen to enter the electoral fray in Bengal as it has done successfully in Bihar for the 2020 Assembly election. There is a possibility that Siddiqui’s party could wean Muslim voters – who have traditionally backed Mamata – away from the TMC and help the BJP. Even if it does not have an impact in the coming election,8 Siddiqui represents a churn among Muslim voters caused by the economic and social backwardness of the community.9

The TMC’s Prospects

Mamata is in many ways the biggest strength and weakness of the TMC. Despite two terms as chief minister, she still enjoys remarkable popularity. CSDS-Lokniti surveys found that in 2019, 43 per cent of respondents favoured the leadership of Mamata compared to 37 per cent for Modi. On the flip side, the TMC is almost synonymous with and over-reliant on Mamata. Though this is not too different from other regional parties, which are either associated with one leader or a family, the TMC’s reliance on Mamata is perhaps even greater. She is the face of the government as well as its election mascot. There has been little effort to nurture a second-tier leadership with the exception of the rapid rise in the TMC ranks of Mamata’s nephew, Abhishek Banerjee, currently a Lok Sabha MP.

Despite the organisational weaknesses of the TMC, it enjoys an advantage over the BJP. The BJP has no leader or face that comes close to matching Mamata’s popularity. In line with the BJP’s election strategies in other states, the party has not projected a chief ministerial candidate in Bengal. While there is speculation about a clutch of BJP leaders, including the state BJP president and MP, Dilip Ghosh, a decision will be made by the party high command if it does win a majority. This strategy has worked in states where the BJP has been pitted against weak or unpopular chief ministers, but could backfire against a popular leader. In addition, there is evidence to suggest that Mamata is popular among women, who have been turning out to vote in larger numbers across India in recent elections.10 Two of the most popular schemes of the West Bengal government are Kanyashree, which provides cash to school going girls, and Swashtya Sathi, which offers a health card issued in the name of the household matriarch. The significance of the women vote is reflected in the TMC’s distribution of election tickets with 50 of the 291 constituencies it is contesting, or 17 per cent, having women candidates.11

The TMC has seen several high-profile defections in the recent past, triggered by the absence of any core ideology in the party, the importance given to Abhishek, disaffection with election strategist Prashant Kishor’s role and the rising fortunes of the BJP. There have even been instances of TMC members, who had been given election tickets defecting after their names, had been announced. The defectors include leaders and former ministers like Suvendu Adhikari who is contesting against Mamata in Nandigram, one of the sites of the anti-land acquisition movement which propelled Mamata to power. While many of them are contesting the coming election, the fielding of so many turncoats could well dilute the BJP’s message that it is different from the TMC. It could also possibly alienate the former Left supporters, some of whom have no affinity towards the BJP’s Hindutva ideology, but were strategically voting against the TMC. It has already led to protests by BJP workers who are unhappy with the new entrants being given preference over those who had been working for the BJP for the past few years. There has even been an instance of candidates, whose names had been announced, being withdrawn in the face of protests.12

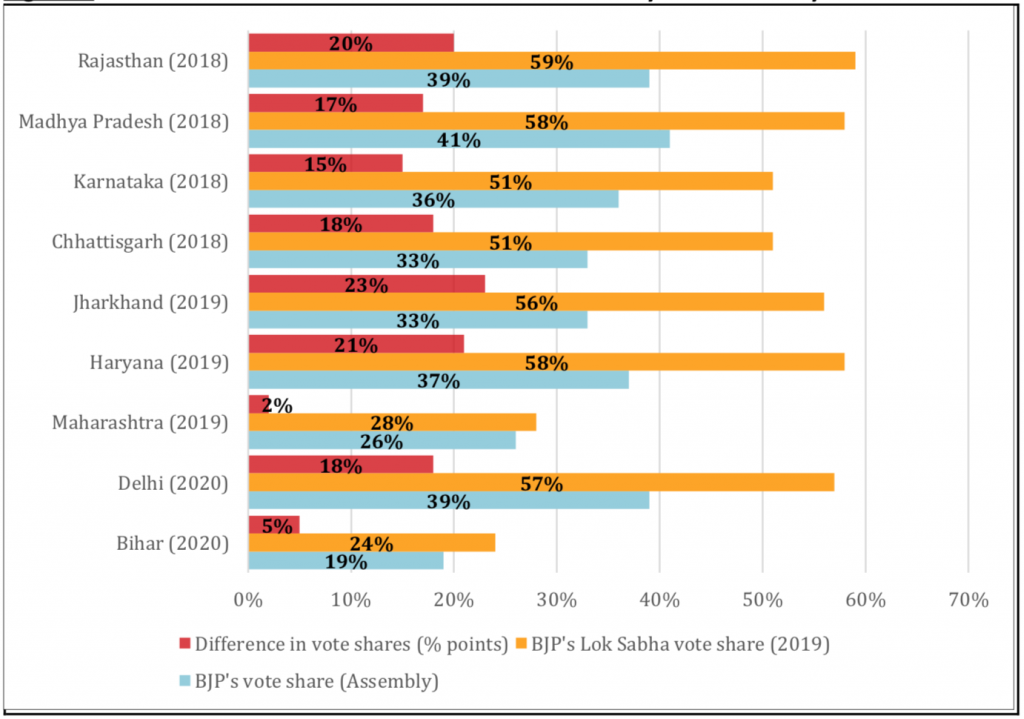

Finally, the TMC could take succour from the fact that the BJP has usually won a significantly lower vote share in Assembly elections, held over the last two years, compared to the general elections (Figure 3). In 2019, the TMC led in 164 Assembly segments, down from 211 seats it had won in 2016, compared to the BJP, which led in 121 Assembly segments in 2019. This performance might be difficult for the BJP to repeat since the 2019 general election was largely a referendum on Modi.

Figure 3: Difference in vote share for BJP in Parliamentary and Assembly elections

Source: Election Commission of India

State of Play

As West Bengal heads into the first phase of a very long election, the TMC announced all its candidates in one go while the BJP has done so in phases. While Mamata leaving her constituency of Bhabanipur in Kolkata to contest in Nandigram against Adhikari was a statement of intent, the BJP has also signalled its resolve to win at all costs by nominating several sitting MPs. These include Union minister Babul Supriyo and nominated MP Swapan Dasgupta, the latter having been forced to resign his Rajya Sabha seat. The BJP has also given tickets to a host of film stars in constituencies in and around Kolkata, where success has eluded the party, in an effort to nominate recognisable names and to reach out to the urban middle class.

As campaigning has started and Mamata and a host of BJP leaders have begun crisscrossing the state, the tenor of the campaign can be gleaned from party slogans and campaign speeches. One of the ways the TMC has pushed back in the recent past against the Hindu nationalist rhetoric of the BJP is by resorting to Bengali nationalism and labelling the BJP as bohiragato or outsiders. The TMC has also encouraged the use of the slogan Joy Bangla to counter Jai Shri Ram. More recently, the TMC has unveiled its campaign slogan, Bangla nijer meyekei chaay (Bengal wants its own daughter), which combines the centrality of Mamata in the party’s campaign even while emphasising the ‘outsider’ tag of the BJP.

However, the BJP’s focus on Hindutva has also forced Mamata to resort to Hindu symbolism and temple visits on the campaign trail. In her first speech in Nandigram, after filing her nomination, Mamata stressed her Hindu identity and proclaimed that she chanted from Hindu scriptures daily.13 The TMC is also strategically fielding fewer Muslim candidates this election compared to 2016, especially in constituencies where the BJP did better in 2019 compared to 2016.14 The BJP campaign and its election manifesto has revolved around TMC’s corruption and nepotism and ushering in a Sonar Bangla (Golden Bengal), taking the cue from a Tagore song which is also the national anthem of Bangladesh.

Conclusion

Irrespective of the results in West Bengal, the election represents a critical moment for the state. When the TMC defeated the Left Front in 2011, it did not dismantle what has been termed ‘party-society’ – where political parties are dominant not only in the public sphere but also in private lives – by political scientist Dwaipayan Bhattacharyya.15 In the short run, the election will be a test of whether a regional party can counter the combination of religious polarisation, a nationally dominant party (with control over government agencies and deep pockets) and the prime minister’s charisma. In the long run, though, the foregrounding of identity politics is likely to change the ground rules of politics in Bengal, including perhaps the institutional arrangements of party-society.

. . . . .

Dr Ronojoy Sen is Senior Research Fellow and Research Lead (Politics, Society and Governance) at the Institute of South Asian Studies (ISAS), an autonomous research institute at the National University of Singapore. He can be contacted at isasrs@nus.edu.sg. Ms Kunthavi, Research Trainee at ISAS, assisted him with the data visualisation. The author bears full responsibility for the facts cited and opinions expressed in this paper.

Photo credit: Facebook/MamataBanerjeeOfficial

-

More From :

More From :

-

Tags :

Tags :

-

Download PDF

Download PDF