Summary

The Voice of the Global South Summit that New Delhi convened in January 2023 is not about returning to the anti-Western ideological tropes of the non-aligned movement. Delhi hopes its renewed engagement with the developing countries will boost its quest for a larger international role and complement its growing strategic partnerships with the major powers, including the United States and Europe.

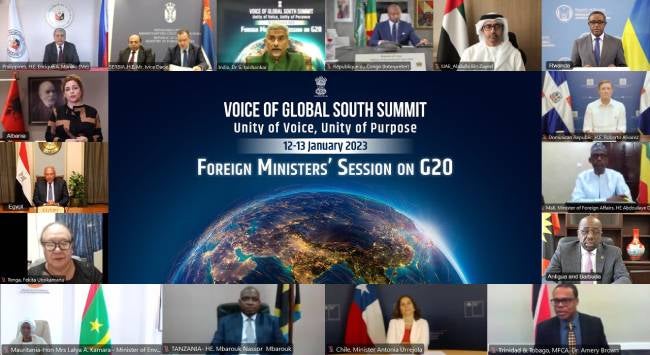

The Voice of the Global South Summit that Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi convened in New Delhi on 12 and 13 January 2023 did not produce any dramatic outcomes. That was not the real expectation in Delhi. India’s main objective was to make global governance work for the developing nations, whose concerns tend to get limited attention in the international forums. The Summit helped India consult with the developing countries in the run-up to the G20 Summit in Delhi, chaired by India this year.

The discussions focused on a number of subjects of interest to the Global South, including financial inclusion, data for development, balancing growth with sustainability, accelerated climate action, the delivery of climate finance by developed countries and the promotion of connectivity and commerce within the Global South.

Addressing the conference, Modi announced a number of new initiatives. These include a project on ‘Aroyga Maitri’, which builds on India’s supply of vaccines to the developing countries during the COVID-19 pandemic, by offering the supply of medication to needy countries in health emergencies.

Beyond the immediate focus on the G20 summit, the forum was also about India reconnecting with a global group of nations that had fallen down India’s post-Cold War diplomatic priorities. Over the last three decades, Indian diplomatic focus has been on restructuring its great power relations, promoting greater cooperation and connectivity in the near and extended neighbourhood.

In the second term of the Modi government, external affairs minister Subrahmanyam Jaishankar has frequently emphasised the importance of re-engaging the Global South. That 125 nations attended the meeting underlines the willingness across the Global South to support Indian leadership in addressing the global challenges that have had a massive impact on the condition of the many developing countries.

The G20 Summit in September 2023 will come just before the political preparations for the 2024 general elections get into top gear. The opposition Congress party has accused Modi of leveraging the G20 for domestic political purposes.

Yet, over the last eight and a half years of his tenure as prime minister, Modi has insisted on taking India’s foreign policy to the masses. He insisted on hosting major diplomatic events outside Delhi. The scores of G20 ministerial and official gatherings are being held in different cities during this year.

It is not clear whether this Summit was a one-off event or a regular feature of Indian foreign policy. But Indian officials made it clear the event was not about replacing the Non Aligned Movement (NAM). Foreign Secretary Vinay Kwatra said, “This summit does not dilute in any way how India engages with other fora, whether it is the Non-Aligned Movement or the G-77.”

Although the Modi government might be aware of the dangers of its reach exceeding its grasp, the foreign policy discourse in Delhi has been exuberant about India’s leadership of the G20 and its plans to reclaim the leadership of the Global South.

Sober reflection, however, would suggest that the current international context is not conducive to major global initiatives. Multilateralism is in the doldrums for two reasons. One is the growing military tensions among the great powers – between Russia and China on one side and the United States (US), Europe and Japan on the other. The deepening India-China tensions are very much part of this reality. The other is the breakdown of the world trading rules and the weaponisation of global finance.

The history of the NAM points to the real difficulty of uniting the Global South in pursuit of common goals. Representing the presumed collective interests of the Global South has become harder today, given the deep economic differentiation and sharp political divergence within the so-called Third World.

Sceptics at home would remind Delhi of India’s own enduring developmental challenges, despite its impressive aggregate gross domestic product and growing economic, industrial, and technological capabilities. Given the size of its population, critics would insist that lifting India towards greater prosperity and sustainable development would automatically improve the condition of the Global South.

At a time when India faces more urgent challenges, including massive security threats on its borders, there is a danger that the pursuit of ambitious multilateralism can become a diffusion of India’s political energies. Yet, an emerging power like India cannot simply be self-centred. Nor should it abandon its longstanding equities in the Global South. While India must remain true to its spirit of internationalism, it must also be conscious of the constraints and limits.

As the world’s fifth largest economy, which is set to be the third largest by the end of this decade, India must share the burdens of maintaining the global order. At the same time, Delhi can continue its long-standing work to democratise the international system in favour of the Global South. Balancing between nationalism and internationalism then becomes a major task for Indian diplomacy.

India is also trying to complement the Global South strategy with its efforts to build strong strategic partnerships with the US and its allies in Asia and Europe. Jaishankar has often talked about India as a “South Western power”.

At the Global South Summit, Delhi deliberately shunned the anti-Western rhetoric that used to dominate NAM summits of the past. Nor has there been any Western criticism of the Indian effort to lead the Global South again. At a time when China has made major inroads into the Global South, greater Indian activism might not be unwelcomed for the Western powers.

. . . . .

Professor C Raja Mohan is a Visiting Research Professor at the Institute of South Asian Studies (ISAS), an autonomous research institute in the National University of Singapore (NUS). He can be contacted at crmohan@nus.edu.sg. The author bears full responsibility for the facts cited and opinions expressed in this paper.

Pic Credit: S Jaishankar’s Twitter Account

-

More From :

More From :

-

Tags :

Tags :

-

Download PDF

Download PDF