Summary

The new regulations instituted by the Indian government to manage social media platforms expand its powers over the internet, rendering it the final arbiter over digital content. While the move syncs with the impulse to rein in big technology companies, India’s regulations offer limited means to hold the government accountable which could undermine the citizens’ rights.

That the Indian government was going to intervene to manage social media platforms was a certainty after the recent feud with Twitter over the platform’s handling of certain critical tweets. Yet, few expected the overhaul that arrived last week. New Delhi has erected a new framework under an existing statute (Information Technology [IT] Act, 2000) to govern the internet, specifically digital news, social media and video streaming. New regulations formed under the IT (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Ethics Code) Rules, 2021 expands government powers over the internet, rendering it the final arbiter over digital content.

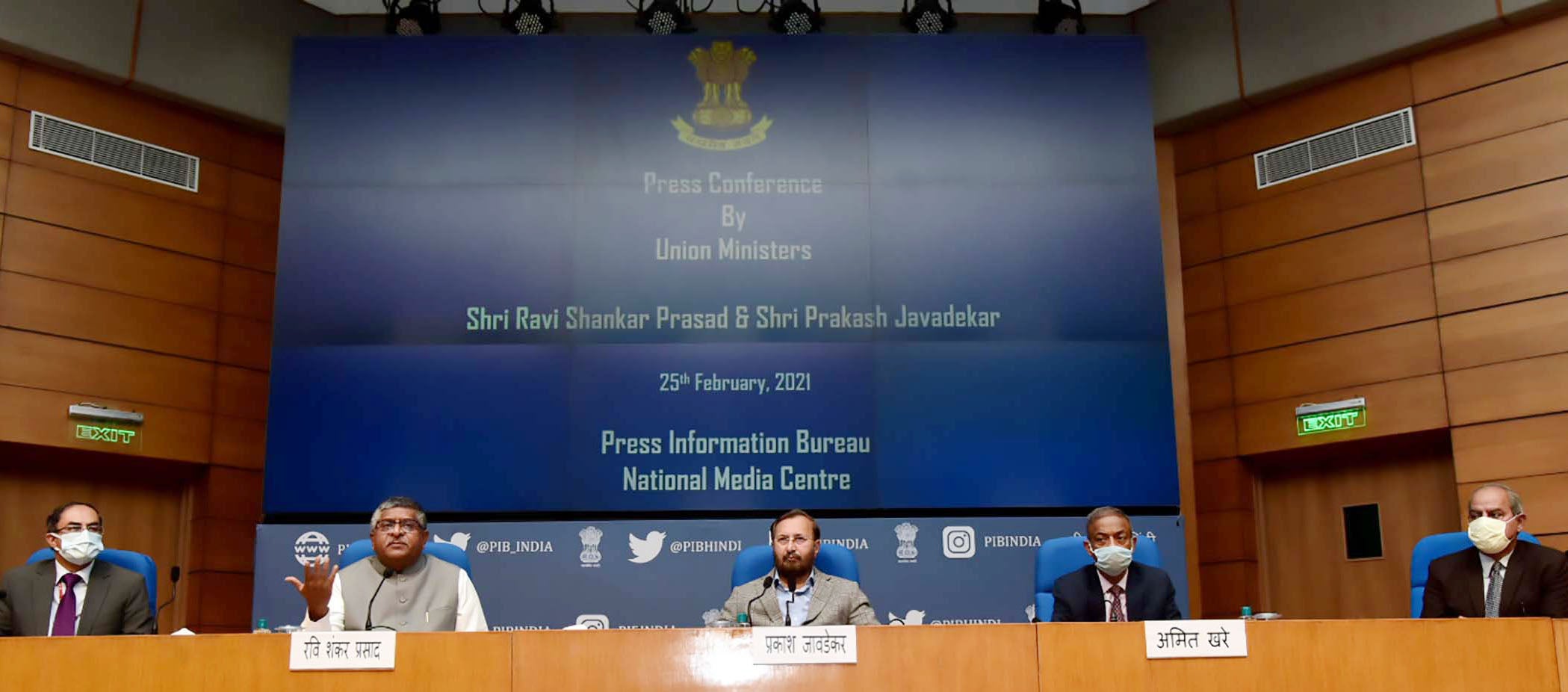

On 25 February 2021, Union Ministers Ravi Shankar Prasad and Prakash Javadekar unveiled new rules for India’s internet intermediaries and digital media platforms to better manage the effects such platforms are having on Indian citizens and society writ large. Before considering new provisions, much has been said about the government’s intent to regulate internet intermediaries and content through the IT Act 2000 and not through a new law. Such a big policy shift could have been undertaken through parliamentary deliberation and consultations. Instead, what we have now are a set of conditions that technology companies must abide by in return for immunity for content published on their platforms. Several big changes are evident through new rules.

First, social media platforms have to abide by new rules that place accountability to manage their platforms. Rules also distinguish between large platforms which are termed as ‘significant social media intermediaries’ and smaller platforms called ‘social media intermediaries’. New provisions, for instance, require users to be given adequate notice before removing content. One big change pertains to identification or traceability. The government now requires messages or content sent through various social media and instant messaging platforms to be identifiable or tied to a user, which will affect how encrypted those services will be in India. Entities like WhatsApp that offer end-to-end encryption might have to change how it operates. Citizens fearing the loss of privacy might refrain from using such mediums leading to self-censorship among users. Compromising security vis-à-vis communications could result in litigation now that India has a constitutional right to privacy. Undoubtedly, traceability requirements undermine privacy and the need to have private conversations. Going ahead, social media firms will also be expected to regularly work with the government to monitor content. They will have to provide information within 72 hours upon receipt of a government order, appoint compliance architecture and officers to coordinate with law enforcement and provide compliance reports based on platform activities. These new rules require platforms to preserve user data for six months, providing the government another opportunity to gather and store data.

Second, on digital media, new rules set up a three tier self-regulatory structure. The first layer focuses on self-regulation, developed by the media entity itself or ‘in-house’. The new rules require companies to address grievances with their content in a time-bound fashion. The second layer will be a body headed by a retired Supreme Court or High Court judge or an independent eminent person. The third and top most tier of the structure will consist of an inter-departmental committee appointed by the central government. Penalties have been added for platforms and firms that fail to comply, resulting in prosecution under the IT Act. Unquestionably, digital and streaming platforms will face additional regulatory burdens that require compliance. Relying on bureaucrats to vet, approve and police content will only increase the discretionary powers of the government when it comes to censoring what and how these digital media outlets operate. Again, this move is being done without parliamentary backing or a new legislation. Opacity reigns. Yet, big technology firms might have no choice but to abide, given India’s booming young internet market marked by millions of young citizens rapidly coming online.

Alarmingly, these new guidelines and rules are being implemented without a data protection law and framework, a cyber environment littered with various threats and risks and no surveillance oversight. Moreover, while new rules emphasise grievance redress, privacy and harm prevention, they could open avenues to stifle or inhibit speech online. More fundamentally, what protection do citizens have to ensure that the government is held accountable while regulating speech on various online platforms and messaging services? What obligation does the government have and, importantly, restrictions when managing these digital platforms? Questions also exist around the constitutionality of these new rules, especially the expansion of the IT Act to include news media and video streaming platforms through executive fiat. All these questions merit answers. Until then, internet oversight in India has arrived through greater political control of the mediums where citizens interact and communicate.

. . . . .

Dr Karthik Nachiappan is a Research Fellow at the Institute of South Asian Studies (ISAS), an autonomous research institute at the National University of Singapore (NUS). He can be contacted at isaskn@nus.edu.sg. Mr Nishant Rajeev is a Research Analyst at the same institute. He can be contacted at isasnr@nus.edu.sg. The authors bear full responsibility for the facts cited and opinions expressed in this paper.

Photo credit: pib.gov.in

-

More From :

More From :

-

Tags :

Tags :

-

Download PDF

Download PDF