Summary

India is and has always been a major exporter of capital relative to its economic size. A large portion of its overseas investments has consistently been directed towards Southeast Asia. Using archival data, this paper traces the history of Indian investments in Southeast Asia in the last 100 years.

It is rarely recognised that India has been a significant source of foreign direct investment (FDI) to the world over the last hundred years. It was a major provider of banking and trading capital to Asia and Africa during the colonial era; it was the third-largest provider of ‘industrial’ FDI among the developing countries during the late Cold War period; and today it is the 25th largest source of FDI in the world and third-largest among the developing countries (after China and Brazil).[1]

Collating data from a variety of archival and secondary sources, this paper demonstrates that Southeast Asia has been one the most significant destinations for Indian outward FDI (OFDI) over the past century. The region’s share in Indian OFDI flow has remained above 20 per cent for most of this period. Notably, the direction of Indian capital within the region has often changed: Burma (now Myanmar) was the favourite investment spot during the colonial era, Malaysia became the favoured destination during the Cold War, Singapore has become the largest recipient of Indian OFDI in the last two decades, and much of the capital expenditure in the recent years has been flowing to the Philippines and Indonesia. The nature of investments has also changed from a heavy emphasis on rural banking during the colonial era and manufacturing joint ventures (JVs) during the Cold War to a more diversified pattern currently with substantial investments going into mining, manufacturing and services.

The history can be divided into four phases: the colonial era, the planning era, the post-liberalisation period and the current deregulation era starting from 2004.

Colonial Era (Before 1947)

Economic exchanges between India and Southeast Asia stretch back to more than two millennia, but the colonial era brought Indian capital into the region at an unprecedented scale. The British Empire and, to lesser extents, the French and Dutch empires needed Indian capital to make their Southeast Asian colonies economically viable. Colonial authorities and European businesses collaborated with Indian and Chinese bankers, traders, industrialists and landlords to develop export industries in the region, integrating them into the global economy and, thereby, pay for colonial rule. Based on data from later periods, one can extrapolate that Southeast Asia was the largest recipient of investments from British India from at least late 19th century.

The Chettiar community from South India became the most well-known instance of Indian capital in Southeast Asia. Chettiars primarily acted as bankers to the rural peasantry in the colonies. Their credit stabilised rural economies and ensured reliable agricultural production, which was bought by European and Asian traders for export.[2]

There are no comprehensive statistics of Chettiar capital circulating in Southeast Asia for most of the colonial period, but the amounts were likely enormous. It is only in the 1920s and 1930s that one can piece together a broad picture. By the late 1930s, Chettiars owned a quarter the total occupied area in the 13 principal rice growing districts of Lower Burma; they held three per cent of coconut plantations and 1.5 per cent of rubber plantations in Sri Lanka; and they held a third of total rice credit in Cochinchina (modern-day southern Vietnam).[3]

Chettiar banking was only one of several forms that Indian capital took in Southeast Asia. A significant amount of money also went into plantations and trading. Although data for these activities is even more sparse, they were likely significant in scale. For instance, Indians owned close to four per cent of land under rubber plantation in Malaya in the 1930s.[4] At the time, one Indian merchant held the virtual monopoly of Thailand’s entire paper trade.

With the onset of the Great Depression in 1929, pressure on Indian capital in Southeast Asia began to ratchet up. Chettiars ended up holding enormous parcels of land because of large-scale loan defaults caused by the economic crisis. They became a lightning rod for nativist backlash in various parts of the region, often portrayed as usurious and exploitative. Colonial governments sought to regulate or restrict their activities in Ceylon, Burma, Malaya and Indochina. During the Second World War, Japanese occupation authorities cancelled a lot of debt held by the Chettiars and expropriated much of their property. Local antipathy spread to other forms of Indian capital as well. For instance, the Thai government took a more jaundiced view of Indian traders after the war.

Notably, recent research has exculpated Chettiars by demonstrating that they did not charge usurious interest rates in Southeast Asia. In fact, the credit they supplied played an important role in the development of the regional economy. The tsunami of defaults during the Great Depression was to their detriment because it locked up their capital into non-performing assets.[5] Unfortunately, they became easy scapegoats for the rising anti-colonial politics of the colonies.

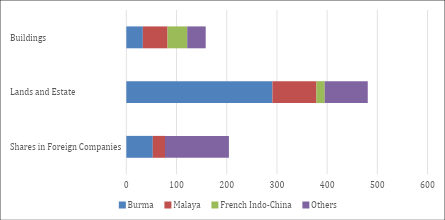

Yet, despite the inter-war-period dislocation and war-time destruction and expropriation, Indian investments in Southeast Asia remained considerable. The first survey of Indian investments abroad was carried out by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) in 1948. Total Indian capital abroad (accounting for only formal economy) was close to ₹1 billion (S$16.2 million). For reference, the total annual outlay for the First Indian Five-Year Plan was just ₹4 billion (S$64.8 million). Of Indian investments abroad more than 60 per cent were in Southeast Asia, totalling ₹598.93 million (S$9.7 million). This data does not include Indian nationals who held tax residency in Southeast Asia at the time. The bulk of this money was tied up in Burma (₹382.13 million) (S$6.19 million), followed by Malaya (₹161.1 million) (S$2.61 million) and Vietnam (₹55.7 million) (S$0.9 million).[6] The distribution of asset classes can be seen below:

Figure 1: Geography of Indian investments abroad in 1948 (₹ million)

Source: RBI Census of Overseas Liabilities and Assets, 1948

Planning Era (1947-1992)

After the launch of centralised planning in 1950, the post-colonial Indian government placed severe restrictions on outflow of investments. It wanted to plough all Indian capital at home to support its ambitious Five-Year Plans, which were being implemented through deficit financing. By 1955, the stock of Indian investments abroad was nearly half of what it had been in 1948.

In the late 1950s, Indian investment began to slowly flow back abroad again under a new policy regime. It was motivated by a peculiar outcome of Indian planning. The Second Plan had focused on building heavy industries. Resultantly, India developed excess capacity for the production of capital goods such as machinery, while lacking simpler consumer goods. The new outward investment policy aimed at creating new export avenues for Indian capital goods. Indian companies would go abroad to set up JVs with Indian machinery. Of necessity, most such JVs were aimed at the Third World, where technology transfer from India was valuable.

The policy was severely restrictive, partly because the government wanted to preserve its limited foreign exchange reserve and partly because it didn’t want its companies to appear as exploitative or predatory to other Third World countries. Accordingly, the policy only allowed for Indian firms to establish JVs with local partners. They were not permitted to own majority stake in the JV. They were also prohibited from investing cash in the JV or remit profits back to India. The only capital invested had to be in form of machinery.[7]

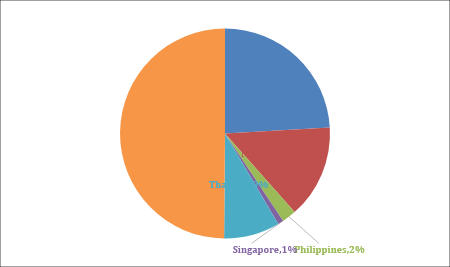

The first experimental JV was a textile mill established in Ethiopia in 1956. A few more investments were made in Africa for geopolitical reasons. However, as the policy gained momentum, Southeast Asia quickly became the most preferred destination. By 1979, the region had received nearly half (₹367.8 million) of all Indian OFDI (₹737.6 million).[8]

Figure 2: Geography of Indian investments abroad in 1979

Source: RBI Archives, Pune

Southeast Asia was attractive to the Indian industry for a combination of historical and economic factors. The region hosted large Indian diaspora. Importantly, the diaspora was assimilated. It did not suffer political or legal discrimination as it did in other parts of the world. As former British colonies, India, Malaya and Singapore shared bureaucratic and legal structure, financial practices and technical standards, easing the transition for Indian firms. Southeast Asian countries had large domestic markets and capacity to absorb Indian technologies. Their open trade policies made them attractive as export platforms to third countries for Indian firms looking to circumvent more restrictive trade policies back home.[9]

Indonesia and Malaya were leading destinations thanks to tax incentives and government support offered to attract investments. Due to the nature of India’s JV policy, almost all FDI until 1970s went into manufacturing – chiefly textiles, palm oil, paper, machinery and automobile parts & assembly. In the 1980s, as rules were relaxed, capital also flowed into consultancy and services.

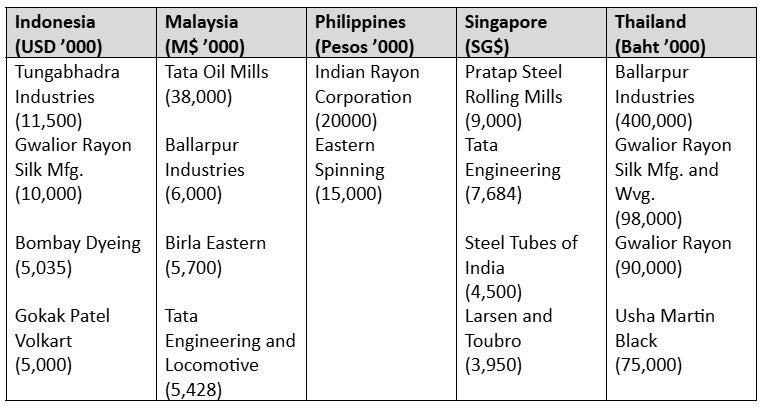

Table 1: List of biggest JVs by total size in different Southeast Asian countries in 1982

Source: RBI Archives, Pune

Post-Liberalisation (1992-2002)

The Indian economic liberalisation of the early 1990s also extended to its OFDI policy. Starting in 1992, the government allowed cash remittances abroad, acquisition of wholly-owned subsidiaries and investments in Western markets. It also began to offer automatic approvals for investments below a ceiling amount. Nevertheless, several restrictions remained in place to preserve Indian foreign exchange reserve.

The new policy emerged from frustration with the old regime that was blamed for anaemic returns and high failure rate of Indian overseas JVs. The liberal policy was also a tool for the government to signal that its overall economic approach was undergoing a “qualitative change…from one of regulator or controller to one of facilitator”. The new policy was meant to allow Indian business pursue technology acquisitions and market access. Moreover, with the new influx of FDI into India in the mid-1990s, the RBI hoped that liberalised capital outflows would contain rupee appreciation.[10]

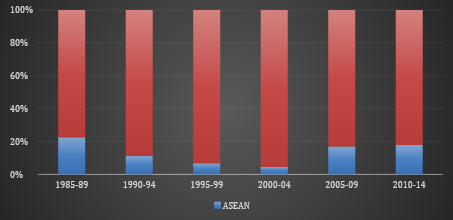

The result was one of the rare periods in history when Southeast Asia’s shared in Indian OFDI declined dramatically from 29.1 per cent in 1985-89 to 4.8 per cent in 2000-04.

Figure 3: ASEAN’s share in Indian OFDI flow

Source: JP Pradhan et al., “Evolution and Pattern of Indian OFDI in ASEAN”, Journal of International Business, 7 no. 2 (2020)

For the first time, Indian capital flowed in bulk to the West. In the early 2000s, North America and Western Europe received nearly half of Indian OFDI. Pent-up demand for Western technology and strategic assets played a role. Moreover, Indian firms were now big enough to be able to buy Western subsidiaries. Much of the OFDI growth was fuelled by the software and communication industry, which had a natural Western orientation. The emphasis Indian OFDI quickly shifted from JVs and greenfield investments to mergers and acquisitions.

The Southeast Asian share of Indian OFDI also fell because of the 1997 financial crisis in the region. The trend was likely a sign of growing divergence between Southeast Asian economies, which were growing more integrated through export-oriented manufacturing supply chains, and Indian economy, which was growing reliant on the information technology (IT) and service sectors.

Nevertheless, the period did see some high-profile Indian acquisitions in the region: Tata Steel purchased NatSteel Asia in Singapore and Millenium Steel in Thailand, Ballarpur Industries bought Sabah Forest Industries in Malaya and Asian Paints bought Berger International in Singapore.

Deregulation Era (2004-Present)

A new phase of deregulation began in 2004, leading to a substantial surge in OFDI flow. The RBI removed hard annual ceiling on overseas investments, linking the limit to firms’ net worth instead. Mutual Funds and individual investors were allowed to invest abroad. (These investments are also recorded as direct investments rather than portfolio investments). Government-owned energy companies Oil and Natural Gas Corporation (ONGC) Videsh and Gas Authority of India Limited (GAIL) could now make unlimited overseas investment. And increasing share of Indian investment now went into raw material extraction.

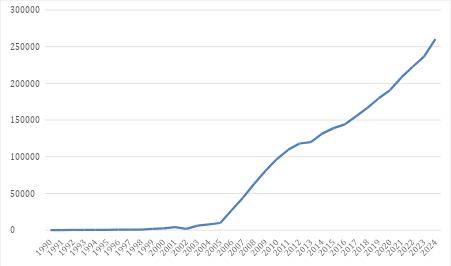

Figure 4: India’s outward FDI stock (US$ million)

Source: UNCTAD FdiFlowsStock Database

Southeast Asia’s average share in Indian OFDI flow returned back to above 20 per cent in the mid-2000s. It has remained so ever since. Singapore is the greatest driver of this trend, thanks to its position as a leading global finance centre (GFC). Indian firms heavily rely on such GFCs to route their investments into third countries or roundtrip back into India. The 2005 India-Singapore Comprehensive Economic Cooperation Agreement, with mechanisms to promote and protect investments, buoyed Indian OFDI flow to the island nation. Until early 2010s, Indian firms relied on several GFCs including Mauritius, British Virgin Islands and Hongkong. However, in the last decade, Singapore has supplanted all other GFCs to become dominant. In the last few years, Singapore is often the largest recipient of Indian OFDI. (It is also the largest source of FDI into India).

Routing through Singapore has made it impossible to accurately capture the geographic distribution of India’s OFDI today. However, the RBI’s data shows that other Southeast Asian still receive substantial investments directly. The Philippines is the most favoured Southeast Asian destination for Indian capital (excepting Singapore) since 2019. A lot of this investment has gone into the IT sector, particularly business process outsourcing. Wipro Information Technology, Business and Process Services (WIPRO) recently made a substantial investment in the country. Indonesia, where Indian companies have acquired several coal mines, is in second place. Next is Burma, where currently most investment is coming from ONGC and GAIL for energy projects, followed by Vietnam. Malaya and Thailand trail far behind. Cambodia, Laos and Brunei have received practically no Indian OFDI in the last five years.

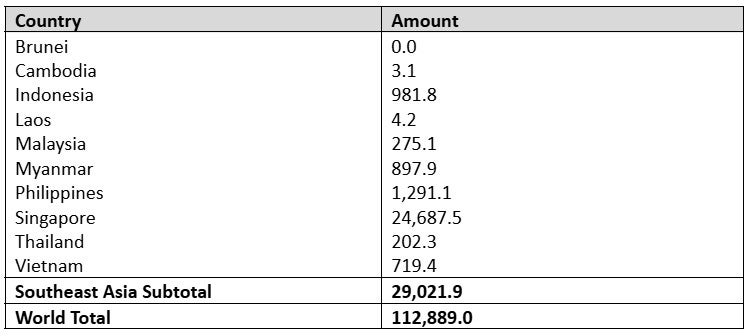

Table 2: Indian OFDI by destination, 2019-2025 (in US$ million)

Source: Calculated from RBI Data. Data missing for Q4 of 2019, Q2 of 2022 and Q3 of 2023, replaced by quarterly average

Invariably, Southeast Asia has received about 25 per cent of total Indian OFDI in the last five years. Even if Singapore is removed from the calculations, US$4.3 billion (S$5.81 billion) has flowed to the rest of the region since 2019.

Conclusion

Southeast Asia has remained a favourite destination for Indian capital since the colonial era. Barring a few brief interludes, one-fifth to a quarter of Indian OFDI has flowed to the region. Moreover, the interludes of receding flow were often caused by policy interventions rather than economic reasons. Perhaps, the two most important factors driving the flow of OFDI are the large, assimilated Indian diaspora and the commercial opportunities the region affords to Indian firms. Time and again, Indian business has seen great potential in the region and invested accordingly. At the same time, Indian capital has played an invaluable role in the economic development of Southeast Asia. As India gears up to become an even larger exporter of FDI to the world, its collaboration with the region will likely only deepen.

. . . . .

Dr Sandeep Bhardwaj is a Visiting Research Fellow at the Institute of South Asian Studies (ISAS), an autonomous research institute at the National University of Singapore (NUS). He can be contacted at sbhardwaj@nus.edu.sg. The author bears full responsibility for the facts cited and opinions expressed in this paper.

[1] Nagesh Kumar, “Industrialization, Liberalization and Two Way Flows of Foreign Direct Investment: The Case of India”, Economic and Political Weekly, 1995; and Calculated from UNCTAD FdiFlowsStock Database.

[2] Raman Mahadevan, Fortune Seekers: A Business History of Nattukottai Chettiars, (Penguin, 2025).

[3] Chester Cooper, “Moneylenders and the Economic Development of Lower Burma”, PhD Thesis, 1959; Ceylon Banking Commission Report (Colombo: Ceylon Govt Press, 1934); and Natasha Pairaudeau, “Indians as French Citizens in Colonial Indochina, 1858-1940”, PhD Thesis.

[4] Sinnappah Arasaratnam, Indians in Malaysia and Singapore (London: Oxford University Press, 1970).

[5] Sean Turnell, Fiery Dragons: Banks, Moneylenders and Microfinance in Burma, (Copenhagen: NIAS Press, 2009).

[6] Calculated from the RBI Census of Overseas Liabilities and Assets, 1948.

[7] “Survey of Joint Ventures Abroad (Policy Matters)”, Reserve Bank of India (RBI) Archives, Pune.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Sanjaya Lall, The New Multinationals: The Spread of Third World Enterprises, (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1983); and K Balakrishnan, “MNCs from LDCs”, Vikalpa, 1982; Sebastian Morris, “Foreign Direct Investment from India”, Economic and Political Weekly, 1990.

Pic Credit: ISAS

-

More From :

More From :

-

Tags :

Tags :

-

Download PDF

Download PDF