India and the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation:

Challenges and Opportunities

Chilamkuri Raja Mohan

21 September 2022Summary

India has taken over the leadership of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) at an opportune and challenging moment. While the Ukraine war and the deepening ties between Russia and China complicate its security environment, the SCO could help Delhi find ways to deepen ties with the Central Asian states that are trying to diversify their partnerships and are open to stronger ties with India.

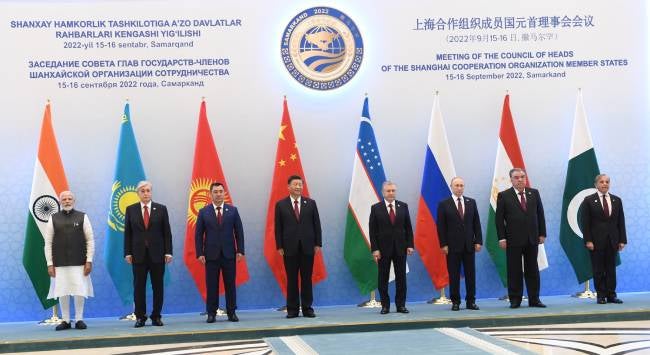

The 22nd summit of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) in Samarkand, Uzbekistan, in mid-September 2022 concluded with India taking over the chair of the regional forum. The mood at the forum was at once optimistic and sombre. More countries have joined the forum and expanded its regional reach. While the SCO consolidates its primacy in Eurasia, many countries, including those in the Middle East and Southeast Asia, are now associated with the SCO.

Iran has now become a full member of the SCO, and the process of admitting Belarus has begun. Egypt, Qatar and Saudi Arabia have now become dialogue partners, and it has been decided to include Bahrain, Maldives, United Arab Emirates, Kuwait and Myanmar as new dialogue partners. This certainly widens the SCO diplomatic field for India. However, the growing attraction of the SCO has not drawn attention away from the complex forces unleashed by Russian President Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. The impact of the Russian invasion has been universal, but the consequences for the Eurasian region are likely to be the most significant and lasting.

For India, particularly, the economic and geopolitical consequences are already weighing heavily. If energy and food security have become challenges, Delhi’s reluctance to criticise its long-standing strategic partner, Russia’s aggression against Ukraine, has cast a shadow over India’s budding relationship with the United States (US) and the West. In Samarkand, Prime Minister Narendra Modi sought to recalibrate Delhi’s position by pointing out to Putin that this is no time for war and emphasising the importance of dialogue and diplomacy.

Making matters even more complicated, Delhi now has reasons to be concerned about the impact of the Ukraine war on Russia’s relations with China. Delhi has long bet that Russia will remain an independent actor in global affairs and will contribute much to India’s pursuit of strategic autonomy.

This faith remained firm when Putin announced an alliance ‘without limits’ with Chinese leader Xi Jinping during a visit to Beijing February 2022. Putin’s invasion of Ukraine began three weeks after that, and it was widely assumed that Moscow had its back covered by Beijing as Russia confronted Europe and the US.

With Putin’s war in Ukraine going badly, the dynamic between Russia and China is shifting, adding an additional layer of concern for Delhi. India is concerned that the failure of the Russian invasion will raise the danger of Russia becoming a ‘vassal state’ for Beijing. In his meeting with Xi on the margins of the SCO, Putin acknowledged China’s interests and concerns on Ukraine and offered to address them. He also underlined the centrality of Russia’s partnership with China and the two leaders and building a new global order with Xi. But the Chinese leader was far more circumspect in his remarks.

Xi did not mention Ukraine nor offer support for Russia’s ‘core’ interests but insisted on the need to “inject stability and positive energy to a world in chaos”. This emphasis on ending the current chaos triggered by Moscow’s war in Ukraine is a recognition that China does not want to be associated with Putin’s failure and face the costs of backing the Russian invasion. Clearly, Xi was offering just the minimum necessary to Putin amidst the prospect that Russia might emerge as a diminished power from the Ukraine conflict. However, Russia has nowhere to turn but to double down on the Chinese partnership.

Delhi is acutely conscious that Xi is taking full advantage of Putin’s weakness. On his way to the Samarkand summit, Xi visited Kazakhstan and reaffirmed strong support for the Kazakh sovereignty. Kazakhstan and many other former Soviet republics are deeply worried about Putin doing a “Ukraine” on them. If Putin could try and undo the independence of Ukraine, he could do the same with other former Soviet republics in Central Asia. Unsurprisingly, these republics are looking to diversify their partnerships. They are looking especially to China and Turkey, and, to a lesser extent, India, to enhance their strategic autonomy from Putin’s Russia and safeguard their sovereignty and territorial integrity.

However, India’s ability to contribute to peace and prosperity in Eurasia is constrained by geography. India does not have direct physical access to the region. And its future Eurasian role is entirely dependent on developing connectivity to Central Asia. PM Modi then rightly focussed on the question of connectivity with the region at the Samarkand summit. Pakistan currently denies transit rights to Afghanistan and Central Asia. Modi has apparently chosen to highlight India’s long-standing demand at the SCO summit. In the last few years, India has focussed on developing access to Eurasia through Iran by building a terminal at the Chabahar port that will allow India to skirt Pakistan and Afghanistan to reach Central Asia. In their meeting on the margins of the SCO, Modi and Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi “reviewed the progress in the development of the Shahid Beheshti terminal, Chabahar Port and underscored the importance of bilateral cooperation in the field of regional connectivity.” Delhi also hopes to mobilise regional support through the SCO to persuade Pakistan to offer transit rights to Central Asia through Afghanistan.

. . . . .

Professor C Raja Mohan is a Visiting Research Professor at the Institute of South Asian Studies (ISAS), an autonomous research institute at the National University of Singapore (NUS), and a Senior Fellow at the Asia Society Policy Institute in New Delhi, India. He can be contacted at crmohan@nus.edu.sg. The author bears full responsibility for the facts cited and opinions expressed in this paper.

Pic Credit: Narendra Modi’s Twitter Account

-

More From :

More From :

-

Tags :

Tags :

-

Download PDF

Download PDF