Implications of Securitising and Desecuritising the Maldives’ Partnerships

Athaulla A Rasheed

23 July 2024Summary

When President Mohamed Muizzu won the 2023 election, international commentariats and observers quickly labelled the Maldives’ new government as pro-China.[1] Due to a country’s potential alignment with China, this type of framing has not been uncommon with small states. China’s port development project in Sri Lanka was flagged by India as a potential security threat to regional order.[2] In the Pacific region, former Secretary General of the Pacific Islands Forum, Dame Meg Taylor, expressly rejected the view that a ‘China alternative’ must resonate with a ‘pro-China’ label when the Pacific Islands seek to expand development cooperation efforts with all willing partners.[3] This type of framing has tended to securitise certain foreign partnerships of the Maldives and could potentially undermine the country’s national security and foreign policy objectives in regional settings.

Introduction

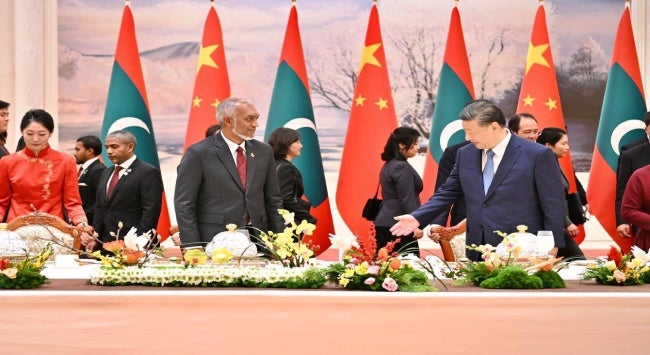

The recent negative-labelling of the Maldives-China relationship has been partly drawn from concerns raised by Indian observers about the renewed engagements between President Mohamed Muizzu and President Xi Jinping’s governments. After the inauguration, Muizzu’s first state visit was to China. During the visit in early January 2024, 20 new agreements were signed between the two countries on economic and security cooperation. Geopolitically, the new agreements can anticipate China’s increased economic and strategic engagements in an Indian Ocean territory and pose potential implications for India’s role in the Maldives’ development and security.[4] As a result, denying the Maldives-China relationship seemed the sensible thing to do for India.

However, the attempt to curb China’s engagements has also tended to categorically securitise the Maldives’ foreign partnerships. Here, securitising involves raising the importance of an issue beyond normal politics and incorporating the matter into security policy and analysis,[5] for example, China’s presence in the Indian Ocean has been pegged to regional security risks. Securitising here means that China’s presence in an Indian Ocean territory can pose an existential threat to the regional order.

This sort of securitisation of foreign partnerships can undermine the Maldives’ national and foreign policy objectives, and, therefore, fail to fully grasp the drivers of politics around its changing foreign partnerships. Framing Muizzu’s government as a ‘pro-China’ administration can limit the regional partners’ focus and dialogue with local authorises and obtain a genuine understanding of what makes a relationship important for the Maldives. Instead, it is important to maintain existing relationships, especially the development and security dialogue between Indo-Pacific partners like India and the new administration in the Maldives.

What Foreign Partnerships Mean to the Maldives

The Maldives is small but has depended heavily on a billion-dollar tourism industry that supports a fast-growing economy. More importantly, the economy has relied on an island infrastructure that has been constantly threatened by the adverse effects of climate change such as sea level rise. Climate change threatens the country’s development potential and long-term sustainability as a sovereign territory. Therefore, achieving sustainable development has required building climate security, such as achieving climate-resilient development through whatever political and economic means necessary. In that, climate-resilient development has required building safer island infrastructure. As a result, the Maldivian governments have long focused on investing in mega infrastructure projects to curd climate impacts; as early as 1990, major Japanese-funded seawall projects were implemented to protect low-lying islands against sea level rise.

Viewing development through a climate lens, the Maldivian government has recently focussed on a ‘safer islands’ approach to development – this type of planning has depended on mega infrastructures such as technologically superior seawalls. In recent decades, the Maldives has achieved safer island infrastructure by reclaiming lands. Land reclamation has helped to build larger and higher islands, to support better infrastructure, that can resist negative environmental change.

Building mega infrastructures has also created an industrial and commercial effect. This involves creating an economy that has attracted foreign investment opportunities in the Maldives. Mega infrastructure projects, such as building and reclaiming lands for safer islands, have required extraordinary means of financing or funding that could not be covered under the national budget. As a result, external aid and foreign investments have an important role in the Maldives.

In economics, the Maldives can present islands of opportunities for foreign investors as a rich tourism industry that holds major shared investments with foreign partners. In development, the government has played a key role in seeking foreign investments, including tourism-related businesses. Moreover, the Maldives’ national and foreign policy priorities have been shaped by the country’s desire to establish aid partnerships to support its development projects.[6] As a result, bilateral and multilateral arrangements have been sought to facilitate investment opportunities from other countries and, recently, the Maldives has enhanced its development partnerships with new extra-regional actors.

Here, some of the new extra-regional actors include China and Turkey. For example, the Maldives-China relationship expanded between 2013 and 2018. This was the time China launched its Belt and Road Initiative – a programme promoting China’s global economic expansion. However, China’s economic expansion in the Maldives’ territory was denied by India from the outset. For the Maldives, the main purpose of strengthening development cooperation with China was to obtain finance and investment to support mega infrastructure development projects; it was not about shaping regional security or balancing India’s regional influence.[7]

External Securitisation and Desecuritisation

The targeted securitisation of the Maldives-China partnership happened during the term of President Abdulla Yameen. Yameen’s efforts to build special investments and partnerships with China to support his development agenda became a growing geostrategic concern for regional actors such as India. In 2014, during Xi’s state visit to the Maldives, nine agreements were signed between the two countries– one of which was for the construction of a US$200 million (S$270 million) Maldives-China Friendship Bridge that was completed in 2018.[8] Multiple mega infrastructure projects, including the Hulhumalé (second largest residential island next to the capital, Malé) land reclamation project, were initiated under these agreements, creating a large financial debt of US$4 billion (S$5.4 billion) (the country’s gross domestic product is US$ 5 billion [S$ 6.8 billion]) owing to China by the end of 2018.

The growth of Chinese investments in the Maldives was viewed by India as a negative venture that could potentially threaten the regional order. The main reason for the negative perception of China’s engagements was to curb the country’s potential rise as an economic and security actor in the Maldives’ territory. For India, China’s presence could threaten India’s role as the regional net security provider for the Maldives.[9] However, this negative viewing had little effect on the expanding engagement between the two countries.

The important thing is that the Maldives has benefited from the mega infrastructure projects. The China-aided bridge has facilitated the movement of economic activities from Malé to the reclaimed lands developed on Hulhumalé island for residential and commercial purposes. For the Maldives, gaining financial assistance to back its development plan was the key purpose of enhancing the partnership with China. This was Yameen’s approach too. The Maldives desired no influence in regional politics and security arrangements. Rather, building infrastructure and safer islands to curb long-term environmental impacts, such as sea level rise, has been the country’s key policy priority.

Development-based foreign policy was evident during the different governments in the Maldives. When Yameen’s government lost in the 2018 election, the preferred partnership was changed from China to India.

In the external viewing of this shift to an India-focused foreign policy, the Maldives’ foreign partnership was desecuritised.

During 2018-2023, India expanded its aid cooperation with the Maldives. Malé foreign policy was seldom linked to a regional security concern.

In the 2018 election, Yameen was replaced by President Ibrahim Mohamed Solih. He instated an ‘India-First’ policy that aligned with India’s neighbourhood-first policy. This change created an opportunity for India to reengage and enhance bilateral ties with the Maldives – an enhanced Maldives-India partnership was also a better setup for the Indo-Pacific partners like the United States (US). For example, the US’ effort to sign a defence cooperation agreement with the Maldives was welcomed by India, given that India and the US are part of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad) and the Indo-Pacific strategy to curb China’s ongoing influence globally.[10]

Sohil’s government was well connected with Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government. As an initial step taken in office, Solih re-evaluated, if not halted, Chinese investments that conflicted with the Maldives-India understandings. More importantly, the shift of preferred partnership to India reduced, if not eliminated, the tension between the Maldives and India that was present during Yameen’s term. The Maldives’ foreign policy no longer had issues with India’s regional security priorities. Rather, India became a primary focus and political and development partner for the Maldives. India’s aid cooperation extended to the development and security domains of the Maldives.

In 2019, among its bilateral commitments, India commenced a US$500 million (S$674 million) project to build three bridges connecting Malé, Villingli, Gulhifalhu and Thilafushi – the idea of multiple bridges to compete against China’s bridge project.[11] This type of geopolitical competition benefitted the Maldives because it opened doors for alternative aid, in the form of foreign loans and credit, to support the national development plan. India’s aid and support for building more bridges also had some level of benefits to Solih’s government, politically. Solih could then locally compete with earlier development efforts – previous government policies – even with his foreign policy shifting priority partnerships to India.

With India, it was different. This time, the Maldives aligned with an Indo-Pacific partner, namely, India. As a result, their partnership was assumed to enforce rules-based regional order. In fact, during 2018-2023, the Maldives saw a period of good governance, the absence of basic human rights violations and a fair performance of the government in dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic. India had no role in establishing Solih’s government as a democratically well-practised administration. This rather had more to do with his party’s ideology. Solih was endorsed by Mohamed Nasheed, then-leader of the Maldives Democratic Party (MDP) – Nasheed was a key founder of MDP and democratic reform and party politics in the Maldives. Historically, the MDP’s ideologies have aligned with democratic best practices. The party, including its leaders, had maintained closer connections with like-minded countries like India, the United Kingdom and the US. They have shared democratic values and promoted rules-based order.

India was naturally aligned with the MDP leadership. Solih’s shift to India was an anticipated outcome of the party and its leadership’s roots of foreign connections. As a result, Modi’s government formed special political bonds with Solih’s administration by enhancing economic defence and security cooperation. Their economic cooperation involved increasing India’s financial aid to support the Maldives’ mega infrastructure development and Chinese debt recovery, including a US$1.4 billion (S$1.9 billion) financial assistance package.[12]

Although it started with multiple mega infrastructure development projects, India’s engagements did not stand out when compared with the developments achieved through China’s aid. India’s support improved mutual engagements in several areas though, including climate adaptation and defence and security efforts. However, Solih’s government did not perform extraordinarily well in terms of overall national development. The COVID-19 pandemic created legitimate reasons for the slow performance. However, the public expected the government to deliver improved public services and support socio-economic performance given that the pandemic-related policies did not completely halt major economic activities, such as tourism, from using innovative approaches. The Maldives showed some potential to adapt and make innovative changes even during COVID-19, that is, it launched an open tourism policy with its individual island-based resort model to allow tourists to visit the country before the international lockdown was lifted.[13]

In terms of mega infrastructure projects, India’s engagement was highlighted around the project to build multiple bridges. The so-called ‘pro-China’ opposition composed of Yameen’s supporters would have expected Solih’s government to perform better, given that his government replaced China with India to undertake some of the country’s major mega infrastructure projects. As a result, the opposition party was able to use India’s failure to complete the bridge project by the end of Solih’s five-year term as a political tool during the 2023 election campaign – this partly contributed to his election defeat.

In retrospect, the Chinese bridge project was completed by the end of Yameen’s term – in politics, this was a positive development project. Yameen lost during the 2018 election against Solih. However, his loss was not caused by a negative outcome of the Maldives-China engagements. Rather, public confidence in his leadership was lost due to several allegations of corruption against him.

India’s main role, in terms of meeting the Maldives’ national development goals, was unclear for two reasons. First, Solih’s approach to development was not rooted in a developmental state policy. Solih failed to better navigate the Maldives’ national priorities through his government’s enhanced partnership with India. New Delhi’s engagements were not securitised or sensitised by the Indo-Pacific observers. As a result, Solih’s government was more inclined to actively participate in regional security along with India – the Maldives was included as part of the Indo-Pacific security dialogue. For example, during Solih’s term, the Maldives’ initiatives in regional security platforms, including the Colombo Security Conclave, India Ocean Rim Associate and Indo-Pacific dialogues, increased and were welcomed by India.[14] By working with India on regional security, the Maldives also enhanced its small state agency in regional politics. This was mutually beneficial for the Maldives and India. The Maldives benefited from India’s defence and security cooperation while Indian gained from narrowing the room for extra-regional actors to influence the security interests of the Maldives. In this context, Solih’s government, however, lacked an adequate focus on national (security) initiatives over regional security interests. Rather, the Maldives engagements in regional security dialogue, including the Colombo Security Conclave, were predominantly about meeting India’s idea of regional security cooperation.

Second, India was focused on strengthening regional security cooperation through its Maldives relationship. India became closely involved in the Maldives’ defence and security activities locally. India placed about 80 Indian military personnel in Maldives to operate two helicopters and a Dornier aircraft for search and rescue and medivac operations.[15] These were engagements undertaken as part of the long-term military-to-military cooperation between the two countries and were not Solih’s initiatives. The objective of the placement of foreign troops was to train the Maldivian military personnel to operate the helicopters and aircraft. However, the long-term stay of India’s troops was unclear to the public and Solih’s government failed to publicly disclose reasons for foreign military presence in the Maldives. The public opinion on this was finally expressed during the 2023 election. This contributed to Solih’s election loss. The public, by a majority vote to opposition candidate Muizzu, endorsed a campaign for the withdrawal of foreign military from the Maldives.

Re-securitising the Maldives-India relations in Domestic Politics

The Maldives has continued defence and security engagements with India; even during 2013-2018, bilateral joint-military operations continued. Joint military exercises, such as DOSTI trilateral maritime security exercises between India, the Maldives and Sri Lanka, have moved the Maldives closer to India in the security domain. With closer political connections with the Maldives during Solih’s term, India was able to shape the Maldives’ defence and security policy at a regional level, especially by denying defence and security-related engagements between the Maldives and China.

Traditionally, extra-regional defence and security arrangements were not expressly welcomed by India. This is not only concerning China, but other like-minded countries, like the US and Australia, have appeared to be less inclined to establish direct engagements with the Maldives in defence and security cooperation. However, with joint regional commitments under the Indo-Pacific Quad, the US-Maldives defence arrangement was not viewed as a negative outlook for India’s regional security posture.[16]

For Australia, India has been an important development and security partner under its commitment to a free and open Indo-Pacific. India has supported Australia’s interests and efforts in the Indian Ocean region and vice versa. In the Indian Ocean space, Australia has been supporting the Maldives’ development for several decades. This included long-term contribution to education and human development, through high education opportunities in Australia for the Maldivians. Australia today plays an active role in defence and security cooperation in the Maldives, including maritime security capacity building between the two countries.

The Maldives-India partnership was not securitised. It was not a security concern for the Indo-Pacific partners like India. The formation of partnerships with like-minded countries has not created issues for regional security. Rather, their relationship has been viewed as important to support India and the Indo-Pacific partner’s efforts to curb China’s potential military expansion in the region.

This type of desecuritisation of foreign partnership – as opposed to securitisation when it came to China – created a willing bias towards India and limited the Maldives’ potential to benefit from alternative and further opportunities. For example, the China alternative was not an option under the Maldives-India agreements.

Locally though, the bias towards India further created room for increasing public scrutiny, mainly instigated by the opposition party leaders, about the growing India’s influence in Solih’s government. In pre-2023 election days, the opposition, including the Muizzu and Yameen’s supporters, instigated an India (military) out campaign to stop India’s (alleged) influence in the internal affairs of the Maldives. India’s military presence in the Maldives, for example, its troops operating the search and rescue operations was framed by many Maldivians, supporting the opposition’s claims, as a potential concern for national security. On top of this, Solih’s government failed to communicate with most of the constituents regarding the importance of the existing defence and security cooperation between the two countries.[17] The reason for not doing so was unclear. It was clear though that Solih’s government prioritised India’s interests such as engaging India in the Maldives’ foreign policy – this was one way of keeping China’s presence minimal during his terms. As a result, some level of Solih’s public accountability was lost prior to the 2023 election, and his government’s dealing with India contributed to his election loss.

After taking office in November 2023, one of Muizzu’s first policy initiatives was to withdraw India’s troops; by the end of May 2024, all Indian military troops had left the country. Solih’s defeat has given credibility to Muizzu’s effort to withdraw Indian troops. Such policies were further cemented by the public during the April 2024 parliamentary election, which secured a supermajority for Muizzu’s party in the Parliament.

This time, domestic politics utilised security as a tool to re-sensitise certain close connections between Solih and Modi’s administrations. While the Maldives-India military cooperation has been an important ongoing endeavour, the opposition was able to create political sensitivity about India’s engagements by pegging them to a national security issue. This public attitude was drawn from the idea that the Maldives should not be leaning towards a single partner. A single priority partner can limit the country’s political independence and potential to expand economically; Muizzu’s government has so far been committed to partnering with all willing countries.

Balanced Diplomacy Against Securitisation

The pre-conceived securitisation of certain foreign engagements, such as Muizzu’s visit to China and Turkey, can prevent external observers from grasping the interests and priorities driving the Maldives’ foreign policy. Working with willing foreign partners had benefits; in this respect, India has continued to be a willing partner and important aid provider in terms of food security.[18] That is why the government has been inclined to expand foreign partnerships and keep open doors for increased foreign investment opportunities, including non-traditional partners like Turkey.

The new initiatives with Turkey involved the launching of Turkish-made tactical drones – a high technology platform – to improve the Maldives’ defence capabilities in the maritime domain surveillance. Likewise, during Muizzu’s 2024 visit to China, about 20 agreements were signed in economic and security cooperation to assist improve the Maldives’ development and security capabilities. In addition to these initiatives, the Maldives has continued to enhance its engagements with India (and Indo-Pacific partners). The 2024 DOSTI military exercise and high-level core group – led by a senior official of foreign affairs – showroom for open opportunities in the Maldives for all willing partners. This aligns with Muizzu’s pledge to balance the internal and external obligations of the Maldives.[19] Muizzu’s visit to India for Modi’s inauguration ceremony in June 2024 further highlighted Malé’s desire to enhance its relationship with New Delhi.[20]

Furthermore, the security of the Indian Ocean is important for the Maldives. The Maldives is a large ocean state and maritime domain covering over 98 per cent of its sovereign territory. Although some level of deterioration of diplomatic ties appeared during and just after the 2023 election, there is an important need for the Maldives to maintain the status quo in terms of regional security arrangements. This includes maintaining continued defence and security dialogue and military-to-military cooperation between the two countries. This military-to-military dialogue must consider both traditional and non-traditional aspects of security the Maldives has been facing, including the implications of climate change on military operations and exercises undertaken by the Maldivian agencies.

In this respect, bilateral and regional cooperation must not be limited to government-to-government formal engagements. Limiting bilateral dialogue to formal government-to-government business can also undermine some of the community-based needs and security interests of the Maldives. For example, just because its government’s policy shifted from an Indo-Pacific partner to China does not necessarily imply that the Maldives would stop communication or investments with its traditional Indo-Pacific partners like India. If the Maldives’ new partnerships get prematurely securitised, it can also create a level of hesitance on the traditional partners’ side to continue the existing dialogue. This could create isolationist-style policies towards the Maldives. This, in turn, may limit future possibilities to guarantee that the Maldives maintains its commitment to rules-based procedures.

On the other hand, India’s proven willingness for ongoing dialogue with regional actors, including the small Indian Ocean states, supports the possibility of a multipolar region. This can help the Maldives promote its open foreign policy without undermining regional rules-based order and security arrangements set by India and its Indo-Pacific partners. In terms of defence and security engagements, the Maldives can align its security policy with the existing regional security system and engage openly in regional security dialogue with India as this island state extends its development cooperation with extra-regional actors such as China. China is not a hostile country towards the Indian Ocean region, for example, other small states, such as Sri Lanka and Bangladesh, have economic and security agreements with China. Beijing is also New Delhi’s important trading partner. Therefore, engaging with China does not by default create security risks but the type and level of engagement can generate views about the potential implications of China-related partnerships in the region. In the Maldives, financial aid and investments have come from India and China. To continue engagement, the Maldives must engage in regional dialogues. This will allow regional actors, including India, to closely observe the Maldives’ foreign policy decisions and align its interests with regional security objectives.

Conclusion

The Maldives has recently switched foreign partnership preference between India and China. The country’s interests in development, progress and security have shaped its main desire to form foreign aid partnerships. As a small island state, the Maldives has been extremely vulnerable to external shocks, climate change and sea level rise. The country must depend on foreign aid to address potential damages and achieve sustainability. As a result, foreign partnerships have been an inevitable part of the Maldives’ development policy.

However, the negative labelling of the Maldives-China partnership has also impacted how the Maldives has been viewed in the regional security space. The Maldives-China relations have often been securitised by the Indo-Pacific partners, including India. This has involved raising concerns about the potential security implications of China’s increased presence in the Maldives’ territory. On the other hand, switching partnership preference back to India – between Yameen’s and Solih’s terms – showed a level of desecuritisation. India’s engagements in the Maldives increased during Solih’s term and enhanced military-to-military cooperation – the Maldives-India’s military cooperation has been traditional and ongoing. However, the Maldives-India relations were not framed as a regional security issue.

In domestic politics though, the idea of securitising the Maldives-India relations was not negligible. India’s close engagements were used as a political tool to criticise Solih’s government by his opposition. By linking India’s military presence to its undue influence in Solih’s administration, the opposition, for example, Muizzu’s party, was able to influence the election results. This type of (domestic) securitisation of the Maldives-India relations or the Maldives-China relations can undermine the Maldives’ foreign policy objective to promote a rules-based order and regional security. The Maldives’ primary objective of forming foreign partnerships has been development focused. This type of external (or internal) securitisation can limit development partners, particularly the Indo-Pacific partners, from fully understanding the priorities of the Maldives. Thus, genuine and continuous dialogue between interested actors is required to promote sustainable engagements and avoid undermining the Maldives’ national objectives. Otherwise, what could happen is that the country will often shift partners, leading to incomplete or less sustainable development engagements influenced by politics.

. . . . .

Dr Athaulla A Rasheed is a former diplomat of the Maldives’ government and holds a PhD in Political Science from the University of Queensland, Australia. He works at the Australian National University and can be contacted at athaulla.rasheed@anu.edu.au. The author bears full responsibility for the facts cited and opinions expressed in this paper.

[1] “Pro-China Party Wins Maldives Election in Landslide”, Australian Broadcasting Corporation, 23 April 2024, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2024-04-23/pro-china-party-wins-maldives-election-in-landslide/103756996.

[2] Chulanee Attanayake, “India’s Answer to China’s Ports in Sri Lanka”, The Interpreter, Lowy Institute, 9 November 2021, https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/india-s-answer-china-s-ports-sri-lanka#:~:text=New%20Delhi%20had%20become%20wary,port%20in%20the%20first%20place.

[3] “Keynote Address by Dame Meg Taylor, Secretary General, The China Alternative: Changing Regional Order in the Pacific Islands”, Pacific Islands Forum, 12 February 2019, https://forumsec.org/publications/keynote-address-dame-meg-taylor-secretary-general-china-alternative-changing-regional.

[4] Nilanthi Samaranayake, “As Tensions with India Grow, Maldives Looks to China”, The United States Institute of Peace, 18 January 2024, https://www.usip.org/publications/2024/01/tensions-india-grow-maldives-looks-china.

[5] Ole Waever, “Securitization and Desecuritization”, In On Security, Ronnie D Lipschutz (ed.), Columbia University Press, 1995, pp. 46-86.

[6] Athaulla, A Rasheed, “Drivers of the Maldives’ Foreign Policy on India and China”, In Navigating India-China Rivalry: Perspectives from South Asia, C Raja Mohan and Chan Jia Hao (eds.), Institute of South Asian Studies, September 2020; Athaulla, A Rasheed, “Small Island Developing States and Climate Securitisation in International Politics: Towards a Comprehensive Conception”, Island Studies Journal 17, no. 2 (2023): 107-29, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.24043/isj.391.

[7] Athaulla A Rasheed, “Ideas, Maldives-China Relations and Balance of Power Dynamics in South Asia”, China; Maldives; South Asia, regional balance of power, constructivism; foreign policy. Journal of South Asian Studies 6, no. 2 (2018): 17, https://esciencepress.net/journals/index.php/JSAS/article/view/2606.

[8] Simon Mundy and Kathrin Hille, “The Maldives Counts the Cost of Its Debts to China”, Financial Times, 11 February 2019, https://www.ft.com/content/c8da1c8a-2a19-11e9-88a4-c32129756dd8; Maldives President’s Office, “Important Agreements Signed between the Governments of Maldives and China”, 15 September 2014, https://presidency.gov.mv/Press/Article/14808.

[9] Rasheeda M Didi, “The Maldives’ tug of war over India and national security”, Carnegie Endowment, 2 November 2022, https://carnegieendowment.org/2022/11/21/maldives-tug-of-war-over-india-and-national-security-pub-88418.

[10] Suhasini Haidar, “India welcomes U.S.-Maldives defence agreement”, The Hindu, 14 September 2020, https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/india-welcomes-us-maldives-defence-agreement/article32601889.ece.

[11] Athaulla A Rasheed, “How Australia Can Win Hearts and Minds in the Indian Ocean”, 360 Info, 18 March 2024, https://360info.org/how-australia-can-win-hearts-and-minds-in-the-indian-ocean/.

[12] Elizabeth Roche, “India Announces $1.4 Billion Package for Maldives”, Mint, 18 December 2018, https://www.livemint.com/Politics/D96QBjzLmBRbxx7Xog21ZJ/India-announces-14-billion-package-for-Maldives.html.

[13] Ministry of Tourism, “Statement of restarting Maldives tourism”, 23 June 2020, https://www.tourism.gov.mv/en/news/statement_on_restarting_maldives_tourism.

[14] Athaulla A Rasheed, “What the Maldivian Election Heralds for Indo-Pacific Security”, East Asia Forum, 19 July 2023, https://eastasiaforum.org/2023/07/19/what-the-maldivian-election-heralds-for-indo-pacific-security/.

[15] David Brewster and A. Athaulla Rasheed, “Rethinking the Maldives-India Security Relationship”, The Interpreter, Lowy Institute, 17 October 2023, https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/rethinking-maldives-india-security-relationship; Athaulla, A Rasheed, “Voters Back Maldives Change in Foreign Policy”, Lachlan Guselli (ed.), 1 May 2024, https://360info.org/voters-back-maldives-change-in-foreign-policy/.

[16] Athaulla A Rasheed, “What the Maldivian Election Heralds for Indo-Pacific Security”, East Asia Forum, 19 July 2023, https://eastasiaforum.org/2023/07/19/what-the-maldivian-election-heralds-for-indo-pacific-security/.

[17] Athaulla, A Rasheed, “Balancing Internal and External Obligations in the Maldives’ Foreign Policy”, East Asia Forum, 23 February 2024, https://eastasiaforum.org/2024/02/23/balancing-internal-and-external-obligations-in-the-maldives-foreign-policy/.

[18] Rezaul H Laskar, “On Maldives’ request, India clears export of food items including rice, wheat”, The Hindustan Times, 5 April 2004, https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/on-maldives.

[19] Athaulla, A Rasheed, “Balancing Internal and External Obligations”, op. cit.

[20] Shishir Gupta, “PM Narendra Modi back at work, engages Maldives Prez Muizzu at President’s banquet”, The Hindustan Times, 10 June 2024, https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/pm-narendra-modi-works-on-at-maldives-prez-muizzu-at-presidents-banquet-101717988893693.html.

Pic Credit: (3) muizzu in china – Search / X

-

More From :

More From :

-

Tags :

Tags :

-

Download PDF

Download PDF