Summary

Pakistan remains entrenched in ideological contradictions, clinging to the outdated ‘Two-Nation Theory’ while refusing to address historical atrocities committed during the 1971 Bangladesh Liberation War. This selective amnesia has led to political fragmentation, with the military’s increasing dominance undermining democracy. The unresolved trauma of 1971 continues to hinder reconciliation with Bangladesh, exposing the tensions between strategic interests and historical memory. Pakistan’s failure to confront its past and evolve beyond its foundational myths deepens its internal crises and limits its political future.

In the affairs of nations, history is rarely past; it is an ever-present force. History exerts its relentless pressures not merely through commemorative ceremonies or nostalgic invocations, but through the wilful choices leaders make, the narratives they preserve and the atrocities they refuse to acknowledge. As Anthony D Smith noted, “no memory, no identity; no identity, no nation”.[1]

In Pakistan’s case, unresolved historical traumas, particularly those linked to 1971, continue to shape its identity, interests and policies. The country stands at a civilisational impasse, caught between memory and amnesia, where foundational myths are being retooled to manage contemporary crises. Two seemingly unrelated events in April 2025 – one in Islamabad, the other in Dhaka – highlight this enduring tension, prompting a deeper reckoning with the moral foundations on which Pakistan was built and how much of that foundation endures today.

Ghosts of an Ideological Genesis

On the domestic front, while standing before a gathering at the Overseas Pakistanis Convention in Islamabad on 16 April 2025, Pakistan’s Chief of Army Staff General Asim Munir’s remarks, while seemingly perfunctory, were loaded with historical undertones and ideological assertion – he reiterated the foundational claim that Pakistanis are “fundamentally different” from Hindus – different in religion, culture, tradition and ambition.[2] “Our forefathers thought we were different in every possible aspect of life”, Munir declared, in what could only be interpreted as a resurrection of the ‘Two-Nation Theory’ – a vision that saw Muslims and Hindus as irreconcilably opposed, and thus justified the creation of a separate homeland.

There was wistfulness in Munir’s speech, a nostalgic rallying cry cloaked in the language of sacred inheritance. Yet, beneath this rhetorical grandeur lay a disturbing undertone – a stubborn retreat into the comfortable absolutism of a theory that has failed its own logic. This reassertion of ideological purity does not merely attempt to summon the spirit of 1947; it attempts to canonise it at a moment when the present realities are rendering such certainties obsolete.

Institutional Trajectory of Munir’s Religiosity

In the decades following Pakistan’s birth, the military stood as a secular and conservative institution, keeping religion at bay, particularly under General Ayub Khan’s rule, which supported social modernism.[3] Military ethos was grounded in discipline, not dogma. However, a subtle mutation began under Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, who, driven by the post-1971 identity crisis and the failure of the ‘Two-Nation Theory’, sought to fuse Islamic symbolism with the state’s nationalist narrative. He used religion tactically – injecting it into textbooks, military culture and even popular media to counter both secular ethno-nationalist opposition and Islamist dissent. This experiment, beginning in military barracks with bans on alcohol and enforced prayer, soon permeated public life. The introduction of Abul A’la Maududi’s puritanical writings into the military marked the beginning of a profound ideological shift.[4] When General Zia-ul-Haq seized power, these embryonic currents crystallised into a systematic Islamisation, aided by the Afghan jihad. The state’s machinery – television, education and intelligence agencies – propagated a historical narrative deeply steeped in religious exclusivism.[5] By the 1990s, even previously secular military officers adopted Islamist rhetoric. What began as a strategic blend gradually became an irreversible metamorphosis of Pakistan’s military and national identity.

Though Zia instrumentalised Islam for authority and legitimacy, his successors have often shown reluctance in demonstrating overt religiosity. Yet, the army’s Islamisation seems to have found complete embodiment in General Munir, who is steeped in religious lineage and Quranic scholarship.[6] Hence, Munir’s invocation of civilisational divergence between Muslims and Hindus marks a pivotal shift in Pakistan’s Islamic identity. It enshrines a hardened Two-Nation ethos, urging generational memory as doctrine.

Munir’s ideological speech, in its timing and tenor, reflects the strategic acuity of Pakistan’s military elite – asserting authority amid a vacuum where civilian politics lies fractured and inert, and the populace effectively disenfranchised. At every step of the governance crisis, the current army chief seems driven as much by his loathing of India as by any brute calculations of power. In Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif’s presence, Munir unmistakably affirmed the army’s dominance, casting aside democratic pretence and confirming that Pakistan’s political fate remains tethered to military command, not civilian authority.

Another revealing strand of Munir’s anti-India oration lay in its references to Kashmir. Munir spoke not as a soldier confined to the discipline of barracks but as a custodian of an ideological frontier – one where territorial revanchism meets religious symbolism. In realist terms, such rhetoric is not accidental – it functions as strategic signalling. When deployed in a domestic setting marked by economic decay and rising social unrest, such incendiary speeches catalyse non-state actors whose operational logic is far less restrained than that of formal state institutions. Munir’s emphasis on Kashmir externally reaffirmed Pakistan’s antagonism toward India, and internally, it reanimated national purpose via a familiar geopolitical cause. The subsequent terror attack on tourists in Pahalgam cannot be extricated from this discursive climate.[7] Ideas do not remain innocent of material consequence. Terrorists and insurgents, emboldened by a renewed sense of ideological licence, are likely to have interpreted such speeches as tacit sanction. In this case, the Pahalgam terror assault seems less a rogue incident than the spectral echo of Munir’s speech.

Dhaka’s Demand

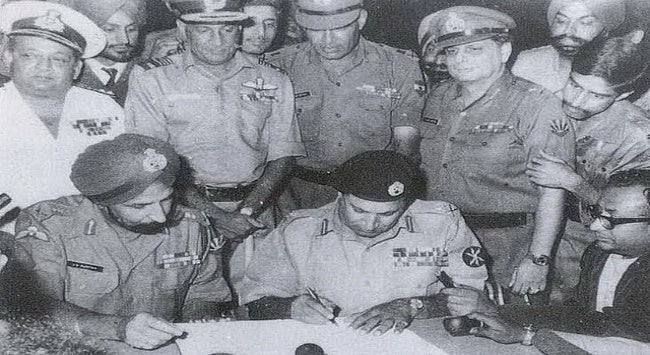

While Munir was invoking Pakistan’s mythical origins, in Dhaka, the Bangladeshi state was confronting the unresolved consequences of that very mythology. For the first time in 15 years, foreign secretary-level talks were held between Bangladesh and Pakistan on 17 April 2025. And, yet the Bangladeshi position was unambiguous: Pakistan should apologise for the atrocities committed in 1971 during Bangladesh’s War of Liberation. In addition to the apology, Dhaka reiterated its longstanding demand for reparations exceeding US$4 billion (S$5.5 billion).[8]

Despite the convenient effacements of official Pakistani historiography, the Bangladesh war was not a remote geopolitical skirmish. It was a brutal campaign marked by systemic rape, mass killings and the wanton use of military force against an unarmed population. It was, in its totality, a secessionist bloodletting born of political alienation, cultural contempt and democratic betrayal. For the ordinary people of Bangladesh, 1971 is not a closed chapter; it is the very origin story of their nationhood.

The fact that the Pakistani state has never issued a formal apology is not a matter of diplomatic negligence. It is a deliberate silence, symptomatic of a deeper pathology within the Pakistani elite. It is the sheer inability to confront the undesirable implications of their own ideological commitments. One Bangladeshi columnist contends that the previous Awami League government intentionally froze relations with Pakistan, not out of national interest, but to reinforce its monopolised narrative of the Liberation War. Though over 50 years have passed since 1971, and most Pakistanis today had no part in those horrors, the memory remains integral to Bangladesh’s identity.[9] The columnist argues that Bangladesh harbours no animosity toward ordinary Pakistanis, but Pakistan’s persistent refusal to apologise for the atrocities of 1971 is historically dishonest and politically corrosive, a moral omission that continues to stain diplomatic reconciliation between the two countries.[10]

The ‘Two-Nation Theory’

To understand the dilemma in which Pakistan finds itself, one must revisit the ideological premise from which it emerged. The ‘Two-Nation Theory’ was less a sociological observation and more an act of adventurous political imagination – an assertion that Muslims and Hindus represented distinct civilisations, incapable of coexistence under a single national framework. From this assertion sprang the utopia of Pakistan: a homeland where Muslims could flourish free from the hegemony of a Hindu-majority India. However, this was a theory which had the tragedies of the future written into it by the devil’s own hand.

Such a theory arises when unnecessary aggression is permitted to dwell alongside utopian idealism – an uneasy coexistence not unlike that of the lion and the lamb, whose companionship is more poetic than practicable. The ‘Two-Nation Theory’ rested on the assumption of a monolithic Muslim identity across South Asia. In doing so, it not only oversimplified the intricate mosaic of linguistic, ethnic and regional distinctions among Muslims but also subordinated internal diversity to the imperatives of realpolitik – an omission whose consequences would reverberate long after partition. Nowhere was this more tragically shown than in East Pakistan, where the Bengali population – Islamic in faith, but distinct in language and culture – found themselves marginalised by the Punjabi-dominated West Pakistani elite.

Their political aspirations were mocked, their electoral victory in 1970 nullified, and their cultural identity dismissed as insufficiently Islamic. When the people of East Pakistan demanded autonomy, the military’s response was so overwhelming, indiscriminate and disproportionate that many in the international community came to regard it as genocide.[11] The ‘Two-Nation Theory’, originally crafted to justify secession from India, had turned inward and devoured itself. A nation born in the name of Muslim unity had violently torn itself apart; it was proof that religion alone cannot sustain a polity without incorporating the principles of social justice and democratic consent.

Cult of Amnesia

The significance of Munir’s remarks cannot be reduced to rhetorical flourish. They reflect a strategic impulse within Pakistan’s military elite. When confronted with severe economic hardships, political fragmentation and the intractable terrorism problem, Rawalpindi is falling back upon the ideological certainties of the past. In this view, history is not a source of lessons but a reservoir of myths to be mined for political legitimacy. Yet, this approach carries grave consequences. Pakistan’s unwillingness to reckon with its inglorious role in East Pakistan five decades earlier and the more recent role in supporting non-state actors against both India and Afghanistan has left it with a stunted political evolution. Even more troubling is the repetition of past mistakes. In Balochistan, one sees an eerie repetition of the East Pakistan dynamic: a disenfranchised region demanding greater autonomy, responded to with militarised suppression. The Pakistani state has internalised neither the tragedy of 1971 nor the costs of its denial.[12] It is content to recite the verses of its foundational myth even as it drowns in the consequences.

Bangladesh’s Realignment

The position of Bangladesh is also not without its contradictions. The regime that emerged following Sheikh Hasina’s ouster has sought closer ties with Pakistan, partly as a strategic recalibration away from India, with whom relations have cooled in recent months.[13] Bangladesh and Pakistan have begun direct trade, with Dhaka importing 50,000 tonnes of rice. They have also resumed flights, military contacts, eased visas, and reportedly started cooperating on security issues.[14] Yet, it remains doubtful whether this diplomatic courtship reflects the sentiment of the Bangladeshi public, for whom 1971 remains sacrosanct. There is, in this juxtaposition, a tension between elite strategy and popular memory.

In a moment of striking audacity, a former officer of the Bangladesh Army, believed to be close to Chief Adviser Muhammad Yunus, recently proposed that Bangladesh should assist China in seizing India’s northeastern states in the event of an Indian attack on Pakistan over the Pahalgam terror incident.[15] The suggestion sparked a firestorm of reaction. Predictably, the interim government in Dhaka was quick to distance itself from these remarks, issuing a rapid disclaimer that these views were neither endorsed nor reflective of official policy. Yet, beneath the swift disavowal lay an underlying current of geopolitical calculation that could not easily be dismissed. This provocative suggestion was not very different from remarks made by Yunus in March 2025 during his visit to China, where he stated that Bangladesh is crucial for India’s northeastern states’ access to the ocean. Yunus even described Bangladesh as the “only guardian” of the Indian Ocean.[16]

While the current rulers in Dhaka may wish to pivot toward Pakistan for geopolitical reasons, the unresolved trauma of 1971 acts as a gravitational force – limiting how far rapprochement can proceed without an apology. What unfolds is a paradoxical choreography of diplomacy – gestures of conciliation offered with one hand, even as the other clutches the unresolved ledger of historical grievance. In this delicate dance, the essence of postcolonial statecraft is laid bare: the imperative to navigate present exigencies through strategic opportunism, while remaining tethered – if not always willingly – to the unforgettable memories of a contested past. It is here, in the uneasy coexistence of pragmatism and remembrance, that the post-imperial world negotiates its fragile equilibrium.

Existential Question

It is worth asking, with the benefit of hindsight and the burden of history: what has Pakistan achieved by clinging to the mantras of the ‘Two-Nation Theory’? Has the reiteration of this founding dogma yielded greater stability, justice or national cohesion? The trajectory since 1971 offers a sobering answer. The state’s ideological rigidity has failed to deliver either economic vitality or strategic depth; instead, it has sown the seeds of internal disunity and deepened international isolation. The existential imperative confronting Pakistan today is no longer the need to assert its separateness from India – that historical project has long exhausted its political utility. The pressing question is whether Pakistan can evolve into a polity capable of engaging its past without resorting to defensiveness or triumphalism.

The secession of Bangladesh was not merely a territorial loss – it was an intense repudiation of the ideological architecture upon which the state was built. Can Pakistan, in light of that reckoning, forge a national identity no longer anchored in perpetual contrast to India? Can it complete the transition from an ideological state – rigid, exclusionary and reactionary – to a more normal state, where identity arises from the plural aspirations of its people rather than from inherited dogmas?

States must eventually confront the consequences of their foundational choices. They must learn to distinguish between the myths that bind and the myths that blind. However, Pakistan continues to remain ensnared by the latter. The experience of other nations offers instructive parallels. After its crushing defeat in 1945, Germany embarked on a long and difficult journey to confront its ignoble past – through truth commissions, public memorials and sweeping educational reforms. South Africa’s truth and reconciliation process after apartheid, despite its flaws, recognised that moral accountability is essential in political change. While Pakistan need not adopt these models in their entirety, it must acknowledge the basic principle they embody; that national coherence is unattainable without an honest engagement with the nation’s own conscience.

Conclusion

The question of accountability for the 1971 war atrocities remains a central obstacle in Pakistan-Bangladesh relations. In global politics, selective amnesia often serves pragmatic ends – setting aside historical grievances in favour of short-term strategic cooperation. Pakistan’s security establishment has embraced this logic, prioritising reconciliation with Bangladesh while avoiding historical reckoning. In doing so, inconvenient truths are obscured to suit shifting power dynamics in South Asia.

Yet, strategic forgetfulness has limits. Some historical wounds resist erasure, particularly when they are deeply embedded in national memory. Bangladesh’s ongoing demand for acknowledgment reflects this resistance. Pakistan’s refusal to confront its past – still shaped by the unresolved contradictions of the ‘Two-Nation Theory’ – has locked the country in a cycle of crisis management. As democratic institutions weaken and power consolidates under the military, the crisis of national identity deepens.

Two events in April 2025 – one in Islamabad, where the army reaffirmed Pakistan’s founding ideals, and the other in Dhaka, where a government born from Pakistan’s violent rupture demanded justice – underscore how unresolved history continues to shape statecraft. They are stark reminders that legitimacy, even in a world driven by strategic interests, is ultimately rooted in historical truth. Without reckoning, reconciliation remains out of reach.

. . . . .

Dr Vinay Kaura is a Non-Resident Honorary Fellow at the Institute of South Asian Studies (ISAS), an autonomous research institute at the National University of Singapore (NUS). He is also an Assistant Professor at the Department of International Affairs and Security Studies, Sardar Patel University of Police, Rajasthan, India. He can be contacted at vinay@policeuniversity.ac.in. The author bears full responsibility for the facts cited and opinions expressed in this paper.

[1] Anthony D Smith, The Ethnic Origins of Nations, Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishing, 1986.

[2] Sushim Mukul, ‘We are different from Hindus: Pakistan Army chief invokes Two-Nation Theory’, India Today, 17 April 2025, https://www.indiatoday.in/world/story/pakistan-army-chief-asim-munir-we-are-different-from-hindus-invokes-jinnah-two-nation-theory-2710336-2025-04-17.

[3] Brian Cloughley, A History of the Pakistan Army: Wars and Insurrections, Karachi: Oxford University Press, 2014.

[4] Seyyed Vali Reza Nasr, The Vanguard of the Islamic Revolution: The Jama’at-i Islami of Pakistan, University of California Press, 1994; and Seyyed Vali Reza Nasr, Mawdudi and the Making of Islamic Revivalism, Oxford University Press, 1996.

[5] Roger Hardy, The Muslim Revolt: A Journey Through Political Islam, 2010, pp. 62-72; See Chapters 5 and 6, Husain Haqqani, Pakistan: Between Mosque and Military, Viking Penguin, 2016.

[6] Ram Madhav, ‘Reading between the lines of Pakistan General Asim Munir’s speeches: Frustrations over instability’, Indian Express, 19 April 2025, https://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/columns/reading-between-the-lines-of-pakistan-general-asim-munirs-speeches-frustrations-over-instability-9952392/.

[7] Ayndrila Banerjee, ‘Asim Munir: The son of an Imam, a ‘muhajir’, and Pakistan Army chief who ‘triggered’ Pahalgam terror attack’, Firstpost, 26 April 2025, https://www.firstpost.com/world/asim-munir-the-son-of-an-imam-a-muhajir-and-pakistan-army-chief-who-triggered-pahalgam-terror-attack-13883004.html; and ‘Pakistan behind Pahalgam attack? Pak army chief’s ‘Kashmir jugular vein’ statement seen as trigger’, Economic Times, 24 April 2025, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/defence/pak-behind-pahalgam-attack-india-sees-link-with-pak-army-chiefs-asim-munirs-kashmir-jugular-vein-statement/articleshow/120535991.cms?utm_source=contentofinterest&utm_medium=text&utm_campaign=cppst.

[8] Nandini Singh, ‘Bangladesh demands Pakistan’s apology & $4.5 bn as reparation of 1971 war’, Business Standard, 18 April 2025, https://www.business-standard.com/world-news/bangladesh-demands-pakistan-apology-war-compensation-1971-jashim-uddin-125041800332_1.html.

[9] Eresh Omar Jamal, ‘Bangladesh deserves an apology from Pakistan for 1971’, Indian Express, 21 April 2025, https://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/columns/bangladesh-deserves-apology-pakistan-1971-9956316/.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Donald Beachler, ‘The politics of genocide scholarship: the case of Bangladesh’, Patterns of Prejudice 41, no. 5, 2007.

[12] Subodh Kumar, ‘Pakistan Army chief’s Baloch rhetoric echoes Yahya Khan’s Bangladesh playbook’, India Today, 18 April 2025, https://www.indiatoday.in/world/story/pakistan-army-chief-general-asim-munir-hardline-speech-general-yahya-khan-two-nation-theory-2710803-2025-04-18.

[13] Sohini Bose, ‘India-Bangladesh Relations and the Pakistan Wildcard’, Observer Research Foundation, 8 April 2025, https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/india-bangladesh-relations-and-the-pakistan-wildcard.

[14] Anbarasan Ethirajan, ‘India watches warily as Bangladesh-Pakistan ties thaw’, BBC, 17 March 2025, https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cge1gxxn07qo.

[15] PTI, ‘If India attacks Pakistan, Bangladesh should occupy Northeastern States: Muhammad Yunus’ aide’, The Hindu, 23 May 2025, https://www.thehindu.com/news/international/if-india-attacks-pakistan-bangladesh-should-occupy-northeastern-states-muhammad-yunus-aide/article69533502.ece.

[16] FE Online, ‘Yunus stirs controversy, calls Bangladesh ‘guardian of the ocean’ and targets India’s Northeast — Here’s what he said during China visit’, Financial Express, 31 March 2025, https://www.financialexpress.com/world-news/yunus-stirs-controversy-calls-bangladesh-guardian-of-the-ocean-and-targets-indias-northeast-heres-what-he-said-during-china-visit/3794639/.

Image: Wikimedia Commons

-

More From :

More From :

-

Tags :

Tags :

-

Download PDF

Download PDF