Summary

The Indian government has imposed one of the longest school closures globally as it suffered through multiple waves of the COVID-19 pandemic. These school closures have revealed the inequities between urban and rural populations, as well as between girls and boys, in adapting to online learning tools. This paper looks at the impact of the prolonged school closure on education as well as on nutrition, with the pandemic possibly increasing malnutrition levels. With schools slowly reopening, the long-term consequences of the pandemic on education and nutrition remains to be seen.

Introduction

Education has been a key component to measure development changes over time and between countries. Its effects range from poverty and inequality reductions to paving the way for sustained economic growth.[1] Other benefits of education include higher wages, social mobility, useful life skills, improved discipline and willingness to change.[2]

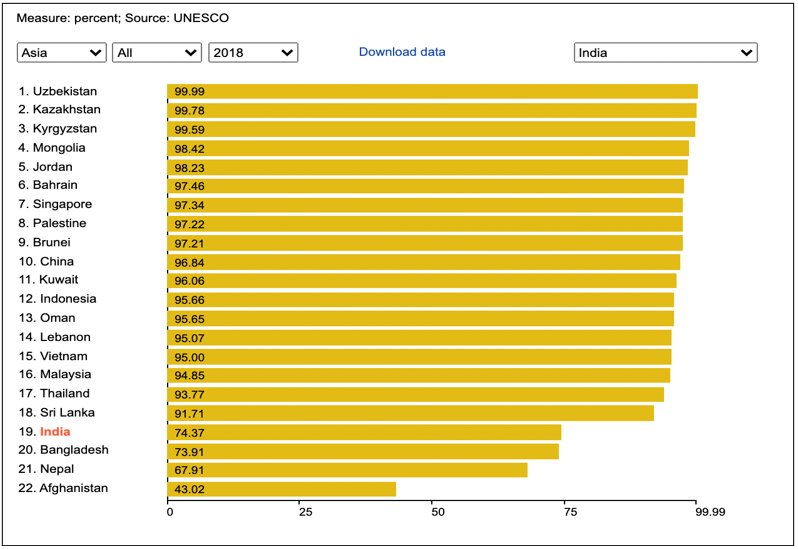

India has fallen behind on its literacy rates (a key, if crude, indicator of educational attainments) vis-à-vis the other South and East Asian countries (Figure 1). As can be seen from Figure 1, India ranks 19th amongst other Asian countries in terms of literacy rates. The World Bank’s Learning Poverty indicator also estimates that 55 per cent of 10-year-old children from India are not able to read a basic sentence, compared to 15 per cent in Sri Lanka and China.[3] Even in terms of female literacy rates, Bangladesh, Nepal and India now almost levelled at an 85 per cent literacy rate despite Bangladesh and Nepal previously lagging behind.[4]

This paper looks at the educational sector in India in the wake of the on-going COVID-19 pandemic.

School Closures and Inequities in Online Learning

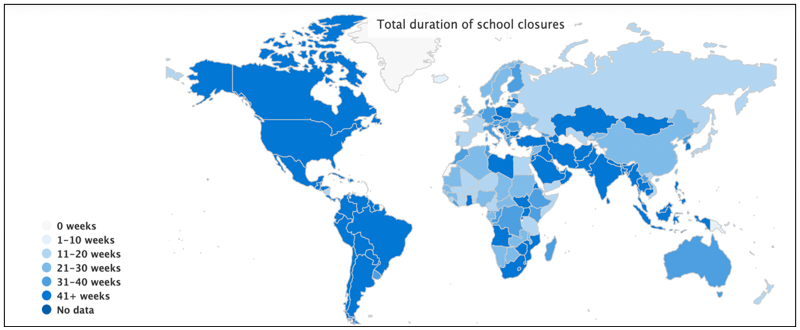

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, India’s poor educational records have been exacerbated, with schools being closed since March 2020. As can be seen from Figures 2 and 2A, schools in India have been closed for the largest number of weeks. The map also reveals that schools in India have been closed for 69 weeks – the longest duration that schools have been closed worldwide.[5]

Figure 1: Literacy rate of Asia[6]

Source: UNESCO

Figure 2: Total duration of school closures worldwide[7]

Source: UNESCO

Figure 2A: Total duration of school closures in India[8]

Source: UNESCO

As a result of this, 1.5 million schools were shut and 247 million primary and secondary students have been out of school since the lockdown of March 2020.[9] Since most primary school students have not gone to school in more than a year, schools have been trying to replace in-person classes with online learning. Teachers and schools have been trying various ways to reach out to their students, using television, radio, WhatsApp groups, group tutoring, Zoom and Skype. Other innovative ways of trying to reach the students include loudspeaker tutorials for those without internet access, and one teacher even built a platform on a tree to access better signal to transmit the lessons.[10]

The reception of these online lessons has been mixed. While many students in urban areas were able to access online lessons, many preferred lessons “in a classroom” where they would not “have to do everything on WhatsApp – submitting assignments, talking to friends, asking doubts”.[11] Many students have over four classes per day on Zoom for their core subjects such as English or Science, and for their extra-curricular activities such as dance or taekwondo.[12] As a result of this, students spend a large amount of time on their computers or phones. However, parents who view technology and digital exposure negatively also prefer lessons in school as “they complain of increased screen time for children”.[13] Some parents also struggle to help their children with the online learning model due to the extended lockdown and the need to handle other domestic chores.[14]

Teachers have also complained that they are unable to build a “rapport with the children” as they usually do in school.[15] They feel that they are unable to observe “body language in class” and “their interaction with classmates” because teachers only see their students online.[16] As a result, many teachers have cited that remote learning has made it more difficult to engage the students.[17]

Yet, many students, especially in the rural areas have not received much or any online learning material due to poor connectivity and lack of access to digital devices. According to a survey, 42 per cent of students aged 6 to 13 years shared that they did not use any type of remote learning during school closures.[18] A report on the Key Indicators of Household Social Consumption on Education in India revealed that less than 15 per cent of rural households had access to the Internet compared to 42 per cent of urban households.[19] Many students faced issues of not having personal devices, poor internet connection, inability to finance an internet subscription, schools not sending materials or difficulty in grasping the online curriculum.[20]

With the pandemic, many families have also been hit with an economic downturn. Students such as Jayasinge are caught between online learning and the economic downturn – “we were struggling to eat, so how would we manage to get a smartphone?”[21] As a result, Jayasinge “spends her days fetching water, cooking meals and hauling cane” instead of going to school.[22] Some of the poorest households are not able to even afford a digital device to access education during the school closures. The prolonged closure of schools has been a challenge and more than 90 per cent of underprivileged parents preferred schools to reopen as soon as possible.[23]

However, the reopening of schools has ebbed and flowed. The Union government allowed schools to reopen on 15 October 2020 but left the exact time and manner of reopening up to the discretion of the individual state education body depending on the prevalence of COVID-19 infections in the area.[24] Some options of reopening included alternate day schooling arrangement, two-day schooling and continued use of online learning, two shifts of school per day, staggered timetables and outdoor classes, among others.[25]

Some states such as Himachal Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh and Uttarakhand reopened their schools after the announcement in October 2020 but had to close them again due to a large number of teachers and students getting infected by COVID-19.[26] In February 2021, schools in Himachal Pradesh, Punjab, Haryana, Uttar Pradesh, Gujarat, Maharashtra, Odisha and Karnataka were to reopen, especially for those in grades 9 to 12 due to the impending board exams.[27] However, the number of cases rose again in March 2021 with India’s second wave of COVID-19 infections. As a result, states such as Himachal Pradesh, Punjab, Delhi, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Maharashtra, Gujarat, Karnataka and Tamil Nadu decided not to open primary schools.[28] However, after 18 months of closure, many schools across India have finally started opening at the start of September 2021.[29] This reopening sees many precautionary measures being put in places such as “stay-at-home-when-sick” advisories, “50% capacity in each classroom, mandatory thermal screening, staggered lunch breaks, wider seating arrangements and no guest visits”.[30] Many schools have also strengthened their infrastructure to improve ventilation, water supply and toilets.[31] However, the impact of the prolonged school closure is yet to be addressed.

Impact of School Closures

The impact of the school closures is wide ranging and affects virtually all dimensions of human development. Here, we will focus on two key aspects, education and nutrition.

Education

The prolonged school closure and the aforementioned poor reception of online learning has meant that many students have fallen behind in terms of curriculum. Many have forgotten lessons that were taught pre-pandemic and are not ready with the necessary fundamental skills that will help them handle a formal grade-based curriculum.[32] A survey of 1,400 underprivileged students revealed that the extended school closure has created a “four year learning deficit”. This means that “a student who was in Grade 3 before COVID-19 is now in Grade 5, and will soon enter middle school, but with reading abilities of [that of] a Grade 1 pupil”.[33]

For instance, in a survey, students in Grade 3 to 5 were asked to read the sentence:

“The school has been closed ever since the pandemic began.”[34] Close to 35 per cent of the students in cities and 42 per cent of the students in villages could not read more than few letters.[35] Similarly, Jean Drèze, an economist, shared how the primary school children that he met in Jharkhand “could not recognise vernacular letters or construct words.”[36] Another student, Radhika, 10, from Jharkhand struggled to write Hindi alphabets “because it has been 17 months since she attended a class, online or offline.”[37] All of these examples tie in with a larger study of 16,000 Grade 2 to Grade 6 students across five states, where 92 per cent had lost at least one language ability and 82 per cent had lost one mathematical ability.[38] Thus, showing how the 18 months of school closure has resulted in stunted or regressing educational growth.

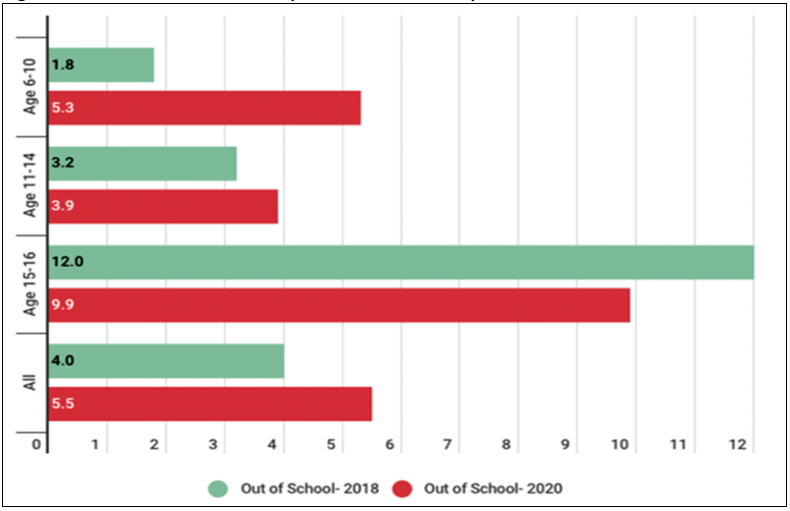

A more distressing impact has been the surge in the number of dropouts. Prior to the pandemic, education in rural areas was seen as a trade-off, where going to school meant an inability to help parents earn a living on the farm or in a shop. During the pandemic, many families were unemployed, financially stressed or in debt.[39] This gives rise to the possibility that many parents in the rural areas may not send their children back to school so as to help the family financially. In Andhra Pradesh, as of mid-July 2021, 60,000 dropouts were estimated and enrolment for Grade 1 was only at 25 per cent.[40] As can be seen in Figure 3, the number of children out of school has significantly increased in the younger age groups. Such a large number of dropouts at such a young age could have a lifelong effect on the productivity of an entire generation.[41] It is also likely that girls are dropping out of school more often than boys, thus putting in jeopardy the progress in closing the gender education gap in recent years.

Figure 3: Out-of-School Children (in %, 2018 and 2020)[42]

Source: ASER (Rural) 2020 Wave 1

The severe financial strain during the pandemic may also lead to an increase in child marriages, leading to an inadvertently larger impact on female children’s education. In a conservative society where 25 per cent of women get married before turning 18, going to school gives these young girls a chance to go out, meet friends, “spend time away from household chores and perhaps chart their own futures”, instead of getting married.[43] Due to the school closures, some girls faced growing pressure from their families to get married. Parents pressure their daughters to get married on the basis that they “don’t have anything to do, … don’t have your studies, you’re just staying here, so let’s go, let’s get [your marriage] settled.”[44] Laxmi Kumari, 18 from Uttar Pradesh, with the help of a non-governmental organisation, managed to avoid an early marriage.[45] However, with school closure and the lack of a smartphone, she has had to cycle to a friend’s house to access the online material, which she has trouble following.[46] Doing well in the upcoming exams might give her leverage to convince her parents for another postponement of her wedding, but she is pessimistic – “right now, I don’t know if I can pass given how much time has been lost”.[47]

On the contrary, wealthier urban parents who have been able to help their children with online learning will be able to send their children back to school on par with their grade. As mentioned by Drèze, “[T]he closure policy seems to be geared to the interests of urban middle-class children, who are safe at home and able to study online, unlike many of their rural counterparts”.[48] Similarly, compared to girls, more boys were able to spend time on their education and had access to phones to connect to online learning. Instead, 71 per cent of girls from low-income families were engaged in household chores versus 38 per cent for the boys.[49] If families can afford after-school extra classes, most choose to send their sons and not their daughters. Even if the sons are younger, parents choose to prioritise the son’s education because girls will be wedded out of the family whereas the son would stay on to take care of his parents.[50] This shows that even though all students had the shared experience of an extended school closure, the impact that the closure had on education varied by class and gender.

Nutrition

The Midday Meal Scheme that is served in local schools is a key incentive for most families to send their children to school, as children receive one cooked meal free of charge. The scheme is targetted at providing students with hot cooked meals, often with proteins such as eggs.[51] Since the inception of the scheme in 1995-96, the enrolment of children in schools has gone up from 33.4 million to 118 million in 2019-20.[52] At its peak, it was benefitting 120 million children across 1.2 million schools.[53] However, with the pandemic and the closure of physical schools, 115 million children have been affected and run a high risk of severe malnutrition.[54] According to the Global Hunger Index, India already ranks poorly at 94 out of 107 countries in 2020.[55]

Nutrition in young children is not only important for its own sake; it also affects the children’s lifelong ability to become healthy and productive adults. At the aggregate level, it is a crucial component of human capital formation, as stunted children perform poorly in schools, miss more days of school (and later, work) due to weakened immune systems and are more likely to develop chronic illnesses (such as diabetes or hearth diseases) which impact their ability to earn a living.[56]

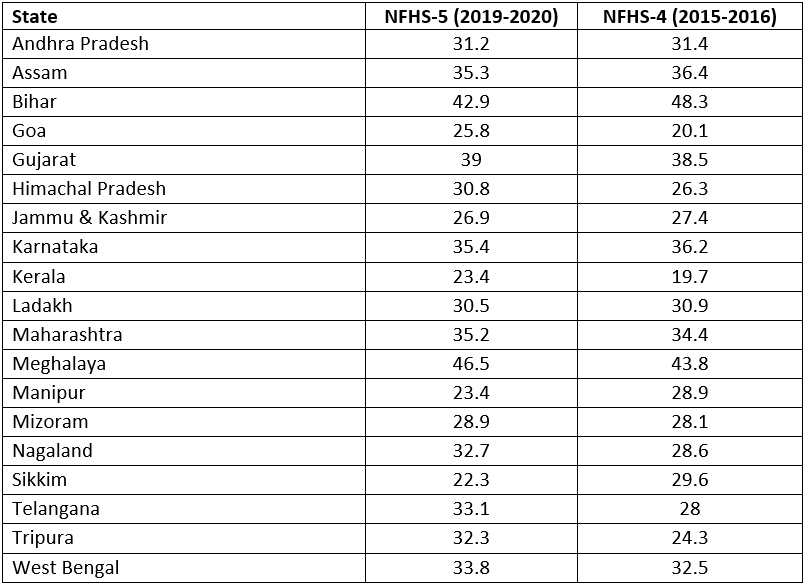

Table 1: Children under 5 years who are stunted (height-for-age) (%)[57]

Note: NFHS = National Family Health Survey

Source: National Family Health Survey 5 (2019-20)

As can be seen from Table 1, the percentage of children stunting has not declined significantly or has even increased from the National Family Health Survey (NFHS)-4 to NFHS-5. Given that this data was compounded pre-pandemic, it is likely that the situation would have worsened significantly due to the school centre closures. Additionally, Anganwadi centres, that is, pre-school learning and nutritional centres for younger children, have also been closed for months, which might have significantly affected the nutritional status of children in the critical age group 0-3.[58] The situation is also likely to be exacerbated from the unemployment and rising poverty levels from the pandemic as well.

To combat this, the central government directed states to deliver the midday meals, either in the form of hot cooked meals or through providing cooking supplies such as grain and oil.[59] Some states have also made attempts to either send rations or cash transfers to families.[60] However, a recent report by OXFAM indicated that 35 per cent of children did not receive their midday meals, eight per cent received hot cooked meals, four per cent received cash in lieu and 53 per cent received dry rations.[61] Such reports raise questions on the effectiveness and implementation of government policy.

The OXFAM report also highlighted the differences in implementation across various states. For instance, Telangana provides hot cooked meals, whereas Chhattisgarh, Haryana and Delhi are providing dry rations, and Bihar providing cash transfers.[62] This means that despite there being one midday meal scheme, there have been disparities in the outcome of the scheme across the various states.

Conclusion

The rising disparities between privileged children who have been able to continue with their education online and the less privileged one (especially girls) who have struggled to access online learning over the course of the extended school closures, will have effects in the long run in terms of social mobility and human capital formation. The findings from the above correlate with studies showing that social mobility is highest in places which are urban, have higher consumption levels, employment, and have “high average education levels”.[63] This already places the privileged children at an added advantage. In the study, while India’s economic growth has benefited a wide section of the population, it has not changed the likelihood of upward mobility for the less privileged classes and castes.[64]

Moreover, the opportunities of upward mobility have increased more for sons than it has for daughters, and less so for daughters from Muslim, Schedule Caste and Schedule Tribe families.[65] Given that India already ranks 76th out of 82 countries in the Social Mobility Index, the potential of equal opportunity for growth does not look optimistic.[66] Upward mobility has also “barely changed from the 1950s to the 1980s.”[67]

Yet, the importance of education is not to be derailed. In fact, according to a study, educational outcomes are the “only” way to measure intergenerational socioeconomic mobility.[68] Education remains a key mechanism for upward social mobility and is crucial especially in the early years. Such learning losses from prolonged school closures could cost India more than U$400 billion (S$542.88 billion) in future earnings, and could also result in social problems, income inequality and a ceiling on upward mobility.[69] Therefore, the prioritisation of the education sector is quintessential not just for the students and teachers, but also for the country’s future growth.

. . . . .

Ms Vani Swarupa Murali is a PhD student at the South Asian Studies Department, National University of Singapore (NUS). She can be contacted at vani@u.nus.edu. Dr Diego Maiorano is a Research Fellow at the Institute of South Asian Studies (ISAS), an autonomous research institute at NUS. He can be contacted at dmaiorano@nus.edu.sg. The authors bear full responsibility for the facts cited and opinions expressed in this paper.

Photo credit: Wikipedia

[1] Harry A Patrinos, “Why education matters for economic development”, World Bank Blogs, 17 May 2016, https://blogs.worldbank.org/education/why-education-matters-economic-development.

[2] William L Miller, “Education as a Source of Economic Growth”, Journal of Economic Issues, vol. 1, no. 4, (1967), pp. 280-96, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4223868.

[3] Amy Kazmin, “India’s schools ‘cannot pick up where they left off’ after Covid”, Financial Times, 29 April 2021, https://www.ft.com/content/b01297e0-65d2-44be-82e2-97b00cb119eb.

[4] Jean Drèze, “Still short of schooling at 74”, The Hindu, 15 August 2021, https://www.thehindu.com/ opinion/still-short-of-schooling-at-74/article35915435.ece.

[5] UNESCO, “Education: From disruption to recovery”, https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse #durationschoolclosures. Accessed on 16 September 2021.

[6] The Global Economy, https://www.theglobaleconomy.com/rankings/literacy_rate/Asia/#India. Accessed on 16 September 2021.

[7] UNESCO, “Education: From disruption to recovery”, https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse #durationschoolclosures. Accessed on 16 September 2021.

[8] UNESCO, “Education: From disruption to recovery”, https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse #durationschoolclosures. Accessed on 16 September 2021.

[9] “Covid-19-induced school closures affected 25 crore Indian children: UNICEF study”, The Hindu, 3 March 2021, https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/closure-of-15-million-schools-due-to-covid-19-impacted-247-million-children-in-india-unicef-study/article33981143.ece.

[10] Amy Kazmin, “India’s schools ‘cannot pick up where they left off’ after Covid”, Financial Times, 29 April 2021, https://www.ft.com/content/b01297e0-65d2-44be-82e2-97b00cb119eb.

[11] Praveen Sudevan, “Why e-learning isn’t a sustainable solution to the Covid-19 education crisis in India”, The Hindu, 11 May 2020, https://www.thehindu.com/sci-tech/technology/why-elearning-is-not-a-sustainable-solution-to-the-covid19-education-crisis-in-india/article31560007.ece.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Amy Kazmin, “India’s schools ‘cannot pick up where they left off’ after Covid”, Financial Times, 29 April 2021, https://www.ft.com/content/b01297e0-65d2-44be-82e2-97b00cb119eb.

[15] Sudevan, “Why e-learning isn’t a sustainable solution to the Covid-19 education crisis in India”.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Niyati Singh, “School closure over Covid-19 may cost over USD 400 billion to India: World Bank”, Hindustan Times, 12 October 2020, https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/school-closure-over-covid-19-may-cost-over-usd-400-billion-to-india-world-bank/story-hxzbNLnXV46hi0bPyOvfVJ.html.

[18] “Repeated school closures due to Covid leading to learning loss in South Asia: UNICEF”, The Indian Express, 10 September 2021, https://indianexpress.com/article/education/repeated-school-closures-due-to-covid-19-leading-to-learning-loss-and-widening-inequities-in-south-asia-unicef-7499111/.

[19] Sudevan, “Why e-learning isn’t a sustainable solution to the Covid-19 education crisis in India”.

[20] Krishna N Das, “Reopen schools or disaster looms, experts tell Indian authorities”, Reuters, 7 September 2021, https://www.reuters.com/world/india/india-reports-31222-new-covid-19-cases-deaths-rise-by-290-2021-09-07/.

[21] Kazmin, “India’s schools ‘cannot pick up where they left off’ after Covid”.

[22] Ibid.

[23] “Covid-19: India school closures ‘catastrophic’ for poor students”, BBC, 6 September 2021, https://www. bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-58432648.

[24] Dheeraj Sharma and Poonam Joshi, “Reopening Schools in India During The Covid-19 Pandemic”, Journal of Tropical Pediatrics, Volume 67, Issue 2, April 2021, https://academic.oup.com/tropej/article/67/2/fmab 033/6290305.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Sharma and Joshi, “Reopening Schools in India During The Covid-19 Pandemic”.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Murali Krishnan, “India: School reopenings signal return to normalcy after COVID catastrophe”, DW, 1 September 2021, https://www.dw.com/en/india-school-reopenings-signal-return-to-normalcy-after-covid-catastrophe/a-59050367.

[30] Ibid.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Sneha Mordani, “School closure have disrupted learning, widened gaps, affected children’s nutrition and health: India task force on Covid-19”, India Today, 17 April 2021, https://www.indiatoday.in/education-today/news/story/school-closure-have-disrupted-learning-widened-gaps-affected-children-s-nutrition-and-health-india-task-force-on-covid-19-1792095-2021-04-17.

[33] Andy Mukherjee, “Covid-19 impact: School lockdowns have robbed a generation of upward mobility”, LiveMint, 8 September 2021, https://www.livemint.com/news/india/covid19-impact-school-lockdowns-have-robbed-a-generation-of-upward-mobility-11631058490533.html.

[34] Ibid.

[35] Mukherjee, “Covid-19 impact: School lockdowns have robbed a generation of upward mobility”.

[36] Bhaskaran Raman and Tanya Aggarwal, “For India’s young generation, the costs of school closure amid Covid-19 are mounting”, Scroll.in, 20 August 2021, https://scroll.in/article/1002980/for-indias-young-generation-the-costs-of-school-closure-amid-covid-19-are-mounting.

[37] Divya Arya, “Covid-19: The Indian children who have forgotten how to read and write”, BBC, 28 August 2021, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-58281442.amp?s=09.

[38] Raman and Aggarwal, “For India’s young generation, the costs of school closure amid Covid-19 are mounting”.

[39] Sharma and Joshi, ‘Reopening Schools in India During The Covid-19 Pandemic’.

[40] Raman and Aggarwal, “For India’s young generation, the costs of school closure amid Covid-19 are mounting”.

[41] Niyati Singh, “School closure over Covid-19 may cost over USD 400 billion to India: World Bank”, Hindustan Times, 12 October 2020, https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/school-closure-over-covid-19-may-cost-over-usd-400-billion-to-india-world-bank/story-hxzbNLnXV46hi0bPyOvfVJ.html.

[42] Mehr Kalra and Shivakumar Jolad, “Regression in Learning: The High Cost of Covid-19 for India’s Children”, Observer Research Foundation, ORF Issue Brief No. 484, August 2021, https://www.orfonline.org/research/ regression-in-learning/

[43] Parth M N, Joanna Slater and Niha Masih, “Schools in India have been closed since March. The costs to children are mounting”, The Washington Post, 30 December 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/ world/asia_pacific/india-coronavirus-school-closures/2020/12/23/7e80f628-3efc-11eb-b58b-1623f626 7960_story.html.

[44] Ibid.

[45] Ibid.

[46] Ibid.

[47] Ibid.

[48] Manavi Kapur, “At least 30 million Indian kids had no way of attending online school during the pandemic”, Quartz India, 5 August 2021, https://qz.com/india/2042509/covid-19-30-million-indian-kids-had-no-access-to-online-school/.

[49] Parth M N, Joanna Slater and Niha Masih, “Schools in India have been closed since March. The costs to children are mounting”, The Washington Post, 30 December 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/ world/asia_pacific/india-coronavirus-school-closures/2020/12/23/7e80f628-3efc-11eb-b58b-1623f62 67960_story.html.

[50] Divya Arya, “Covid-19: The Indian children who have forgotten how to read and write”, BBC, 28 August 2021, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-58281442.amp?s=09.

[51] Parth, Slater and Masih, “Schools in India have been closed since March. The costs to children are mounting”.

[52] Dheeraj Sharma and Poonam Joshi, “Reopening Schools in India During The Covid-19 Pandemic”, Journal of Tropical Pediatrics, Volume 67, Issue 2, April 2021, https://academic.oup.com/tropej/article/67/2/fmab 033/6290305.

[53] Sneha Mordani, “School closure have disrupted learning, widened gaps, affected children’s nutrition and health: India task force on Covid-19”, India Today, 17 April 2021, https://www.indiatoday.in/education-today/news/story/school-closure-have-disrupted-learning-widened-gaps-affected-children-s-nutrition-and-health-india-task-force-on-covid-19-1792095-2021-04-17.

[54] Ibid.

[55] Kapur, “At least 30 million Indian kids had no way of attending online school during the pandemic”.

[56] J Chiriyankandhat, D Maiorano, J Manor and L Tillin, The Politics of Poverty Reduction in India – the UPA Government 2004-14, (Hyderabad: Orient Blackswan, 1 January 2020). Chapters 3 and 5.

[57] “National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5) 2019-20”, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, http://rchiips. org/NFHS/NFHS-5_FCTS/NFHS-5%20State%20Factsheet%20Compendium_Phase-I.pdf.

[58] Divya Murali and Diego Maiorano, “Nutritional Consequence of the Lockdown in India: Indications from the World Bank’s Rural Shock Survey”, Institute of South Asian Studies, 6 April 2021, https://www.isas.nus.edu. sg/papers/nutritional-consequence-of-the-lockdown-in-india-indications-from-the-world-banks-rural-shock-survey/.

[59] Manavi Kapur, “At least 30 million Indian kids had no way of attending online school during the pandemic”, Quartz India, 5 August 2021, https://qz.com/india/2042509/covid-19-30-million-indian-kids-had-no-access-to-online-school/.

[60] Parth M N, Joanna Slater and Niha Masih, “Schools in India have been closed since March. The costs to children are mounting”, The Washington Post, 30 December 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/ world/asia_pacific/india-coronavirus-school-closures/2020/12/23/7e80f628-3efc-11eb-b58b-1623f6 267960_story.html.

[61] Sneha Mordani, “School closure have disrupted learning, widened gaps, affected children’s nutrition and health: India task force on Covid-19”, India Today, 17 April 2021, https://www.indiatoday.in/education-today/news/story/school-closure-have-disrupted-learning-widened-gaps-affected-children-s-nutrition-and-health-india-task-force-on-covid-19-1792095-2021-04-17.

[62] Ibid.

[63] Sam Asher, Paul Novosad and Charlie Rafkin, “Intergenerational Mobility in India: New Methods and Estimates Across Time, Space, and Communities”, February 2021, https://paulnovosad.com/pdf/anr-india-mobility.pdf.

[64] Ibid.

[65] Ibid.

[66] “India ranks low at 76th place on global Social Mobility Index”, The Hindu, 20 January 2020, https://www.thehindu.com/business/india-ranks-low-at-76th-place-on-global-social-mobility-index/article30607184.ece.

[67] Sam Asher, Paul Novosad and Charlie Rafkin, “Intergenerational Mobility in India: New Methods and Estimates Across Time, Space, and Communities”, February 2021, https://paulnovosad.com/pdf/anr-india-mobility.pdf.

[68] Ibid.

[69] Niyati Singh, “School closure over Covid-19 may cost over USD 400 billion to India: World Bank”, Hindustan Times, 12 October 2020., https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/school-closure-over-covid-19-may-cost-over-usd-400-billion-to-india-world-bank/story-hxzbNLnXV46hi0bPyOvfVJ.html.

-

More From :

More From :

-

Tags :

Tags :

-

Download PDF

Download PDF