Summary

Between January and March 2022, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi visited all the countries in South Asia, apart from Bangladesh and Bhutan. His visit highlighted the indispensable nature of the region to China.

Introduction

In recent years, Beijing has attempted to expand its influence in South Asia through its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Six out of eight countries in the region – Sri Lanka (2014), Bangladesh (2016), Afghanistan (2016), Pakistan (2017), Nepal (2017) and the Maldives (2017) – have signed a memorandum of understanding (MoU) with China on the BRI. When the COVID-19 pandemic was at its peak, affecting millions of lives and exacerbating the South Asian countries’ economies, China stepped forward to provide medical and financial assistance to the region. Moreover, China hosted a series of virtual dialogues with Pakistan, Nepal and Afghanistan, where they discussed measures to combat the pandemic. The first meeting was held in July 2020, the second meeting in October 2020,[1] and the third on 27 April 2021.[2]

After the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic began to subside, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi visited Sri Lanka and the Maldives in early January 2022, as a part of his five-nation trip to Eritrea, Kenya and the Comoros. A month later, he visited Pakistan, Afghanistan, India and Nepal. This paper analyses the significance of Wang Yi’s visits to the South Asian countries.

Expanding Cooperation with the Island States

In 2022, Wang Yi added the Maldives and Sri Lanka to the list of countries that the Chinese foreign minister traditionally visits at the start of each new year.[3] This initiative demonstrates that Beijing’s policy circles recognise the strategic criticality of South Asia.

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic ties between China and the Maldives. Since President Ibrahim Mohamed Solih took office in 2018, the Maldives has pursued an ‘India first’ policy, widening its distance from Beijing. Debt is the primary source of disparity between Malé and Beijing; the island nation owes approximately US$1.4 billion (S$1.9 billion) to China.[4] Under his leadership, Solih sought to renegotiate debt terms and reduce borrowing from Beijing.

The two countries signed five agreements during Wang Yi’s visit to the Maldives on 8 January 2022, promising to cooperate on economic development and public health. As a partner country of the Beijing-led BRI and a key island state in the Indian Ocean, the Maldives is a crucial partner for China’s foray into the Indian Ocean. As a result, China hopes to steer the bilateral relations in the right track.

This year also marks the 65th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic ties between China and Sri Lanka and the 70th anniversary of the signing of the Rubber-Rice Pact,[5] which is regarded as the beginning of their bilateral trade. After Colombo passed the Colombo Port City Economic Commission Act in May 2021, China’s infrastructure cooperation with Sri Lanka has made significant progress. The act provides legislative guarantee for the Colombo Port City project undertaken by China. The island state also agreed to jointly build the Colombo Port East Terminal Project with China; this project had been previously assigned to India but was cancelled in 2021.[6]

During the meeting with his Sri Lankan counterpart on 10 January 2022, Wang Yi suggested holding a forum on the development of the island states in the Indian Ocean, showing concerns on the interests of the island countries. His visit affirms the budding friendly cooperation between China and Sri Lanka and builds a solid and stable foundation for the long-term development of bilateral relations.[7]

Pakistan: Most Reliable Partner

The main purpose of Wang Yi’s visit to Pakistan in late March 2022 was to attend the Council of Foreign Ministers of the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) as a special guest. It was the first time a Chinese foreign minister participated in such a meeting, underscoring China’s cordial friendship with the Islamic states and extension of diplomatic support to Pakistan. During the opening ceremony, Wang Yi commented on the issue of Jammu and Kashmir (J&K), saying, “we have heard again today the calls of many of our Islamic friends. And China shares the same hope.”[8] Notably, China’s position on J&K has not changed much since the government of India revoked special provisions enjoyed by J&K under Article 370 of the Indian constitution and bifurcated the state into two Union Territories in August 2019.[9]

During this visit, China inked five new agreements with Pakistan which focussed on mutual recognition of higher education certificates and degrees; joint research centre on earth sciences and agriculture.

Afghanistan: Consolidated Promise

After Pakistan, Wang Yi paid a surprise visit to Afghanistan. He was the first senior Chinese official to do so since the Taliban took over the country in August 2021. The Islamic State-Khorasan Province, as well as the East Turkistan Islamic Movement, pose security challenges to China’s western frontier. Beijing is concerned that Uyghur separatists could be absorbed by existing and new terrorist organisations, which would then launch cross-border attacks on Xinjiang and endanger Chinese-led projects in Afghanistan.[10]

Wang Yi’s visit is seen as a consolidation of the Chinese commitment to aid in Afghanistan’s reconstruction. The Taliban’s Acting Deputy Prime Minister Mullah Abdul Baradar, promised Beijing that Afghanistan was ready to develop friendly relations with China and that no terrorists or anyone engaged in anti-China activities would be allowed to operate from Afghan territory.[11] The Taliban administration has also expressed interest in participating in the forthcoming BRI meeting in Beijing. In response, Wang Yi maintained that if the Taliban fulfil their promises and makes more progress toward building an inclusive government, formal diplomatic recognition of the interim government will be “an act of following the natural course”.[12]

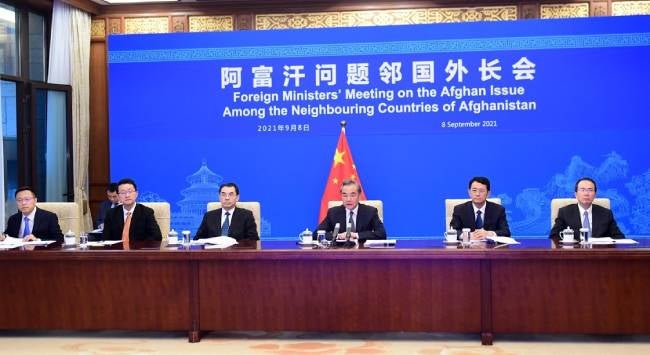

Wang Yi’s visit was followed by the third meeting of the foreign ministers of Afghanistan’s neighbouring countries, (Russia, Pakistan, Iran, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan)

– hosted by China in Tunxi in Anhui Province – on 30 and 31 March 2022. The parties issued a joint statement and agreed on ‘The Tunxi Initiative’ which focuses primarily on joint cooperation to support economic reconstruction and regional connectivity with Afghanistan.[13] Additionally, the parties agreed to create regular consultation mechanism and three working groups to address political, economic and security matters relating to Afghanistan. Acting Foreign Minister Amir Khan Muttaqi of the Taliban was also in attendance; a symbolic move highlighting that the Taliban interim government is politically recognised by the countries present.

India: A Potential Ice-breaking

Wang Yi’s unannounced visit to New Delhi was the first after the Galwan Valley skirmishes in May 2020 and comes amid bilateral tensions. China’s partnerships with the other South Asian countries, India’s role in the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue and growing alignment with other major powers have escalated Sino-India tensions.[14] However, trade relations between China and India have continued to rise after 2020, and even reached a record high of US$125.6 billion (S$171.28 billion) in 2021. In March 2022, India officially approved 66 investments totalling to US$1.79 billion (S$2.43 billion), the majority of which came from Chinese companies.[15] Moreover, in a rare demonstration of unity over the Ukraine crisis, China and India avoided publicly denouncing Russian actions in Ukraine, and both countries abstained during the United Nations Security Council’s vote on the matter in March 2022.

During the meetings with India’s National Security Advisor Ajit Doval and External Affairs Minister S Jaishankar, Wang Yi talked about Sino-India border issues, particularly the disengagement and de-escalation at the Line of Actual Control in Ladakh. Professor C Raja Mohan observed that Wang Yi’s visit signalled a high-level Chinese political effort to end the impasse amid the rapidly changing global equations following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.[16]

However, India’s démarche to China over Wang Yi’s J&K remarks at the OIC meeting overshadowed the ice-breaking visit. India’s Ministry of External Affairs spokesperson Arindam Bagchi stated that China has no locus standi to comment on India’s internal affairs.[17]

During his talks with Wang Yi, Jaishankar insisted that bilateral ties could not be normalised if the situation on the Sino-India border remained “abnormal”. In contrast, it appears that China prefers to prioritise the development of broader bilateral relations while putting border conflicts aside. The disagreement on the border cannot be resolved in the short term. Even if no mutual consensus could be reached, Beijing firmly believes that dialogue is better than none. During his conversation with Jaishankar, Wang Yi declared that China would not seek a “unipolar Asia”, which assuaged Delhi’s worries about Chinese aggression to some extent.[18]

Nepal: A Pre-emptive Diplomacy

Wang Yi’s visit to Nepal was the first by a senior Chinese official since President Xi Jinping’s trip to Kathmandu in October 2019. This implies the continuing significance of the Himalayan state in Beijing’s foreign policy agenda.

In the last week of February 2022, Nepal ratified the “much-debated” American-sponsored Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) Compact, which it signed in 2017. The agreement focuses mainly on infrastructure, but many observers regard it as a pact with the strategic intention of competing with China’s BRI. The MCC may also potentially alter the dynamics of geopolitics in the Himalayan region. Previously, Nepal was hesitant to approve the MCC due to domestic opposition. However, the MCC was ratified once a ‘pro-India’ Prime Minister Sher Bahadur Deuba came to power.[19] For China, Nepal’s participation in the MCC would make the Himalayan state part of the United States’ (US) Indo-Pacific Strategy, posing a threat to China’s border security.

China and Nepal signed nine agreements during Wang Yi’s recent visit, but none of them were related to the BRI. Both countries signed an MoU on the BRI in 2017. Since then, both have coordinated to build the Trans-Himalayan Multi-Dimensional Connectivity Network, which has resulted in Nepal receiving many investments in infrastructure development. In 2020-21, Chinese investors pledged US$184.8 million (S$251.97 million) in foreign direct investment into Nepal, accounting for nearly 70 per cent of the total investments committed by foreign investors.[20] However, the progress of the project has been relatively slow, with just the Gautam Buddha International Airport and Pokhara Regional International Airport completed.

The two countries harbour different views and expectations on the BRI loan rate and duration of projects. Kathmandu is likewise influenced by the concept of the “debt trap diplomacy”, as many political analysts described.[21] Correspondingly, China has emphasised its support for Nepal’s pursuit of independent policies in an effort to persuade the Himalayan country to keep a safe distance from the US. Wang’s visit partially achieves the stated goal as Nepal has vowed not to allow its territory to be used against any neighbouring countries.

Conclusion

Wang Yi’s visits to the South Asian countries shows the high level of importance Beijing attaches to them. Interestingly, Dhaka was missing from the itinerary. The main reason could be that Wang Yi had already met with his Bangladeshi counterpart, A K Abdul Momen, in Tashkent in July 2021.

Wang Yi’s visit cannot be seen as an isolated event from Beijing’s efforts to deepen its influence in South Asia through the BRI and pandemic diplomacy. China is expected to adopt a two-pronged strategy in South Asia in the future and it will try to check its bilateral relations with India so that they do not spiral out of control. However, some commentators have argued that China’s increased diplomatic engagement and assistance to the small South Asian countries is a strategy to limit India’s influence in the region. At present, China’s presence in South Asia is expanding beyond economics. Moving forward, Beijing would require a greater, multidimensional effort to advance its long-term strategic interests in the region.[22]

. . . . .

Dr Amit Ranjan is a Research Fellow at the Institute of South Asian Studies (ISAS), an autonomous research institute at the National University of Singapore (NUS). He can be contacted at isasar@nus.edu.sg. Mr Zheng Haiqi is a PhD Candidate in the School of International Studies, Renmin University, China, and an ISAS Non-Resident Fellow. He can be contacted at zhenghaiqi@ruc.edu.cn. The authors bear full responsibility for the facts cited and opinions expressed in this paper.

[1] Meera Srinivasan, “China chairs second multilateral meet with South Asian partners amid COVID-19”, The Hindu, 12 October 2020, https://www.thehindu.com/news/international/china-chairs-second-multilateral-meet-with-south-asian-partners-amid-covid-19/article33083109.ece.

[2] Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, “Wang Yi Hosts Video Conference of Foreign Ministers of China, Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka on COVID-19”, 27 April 2021, https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/zxxx_662805/t1872178.shtml.

[3] “Chinese FM recaps New Year trips to African, Asian countries”, Xinhua Net, 11 January 2022, https://english.news.cn/20220111/af07d427503b4070a4afa48afb619f49/c.html

[3] “Chinese FM recaps New Year trips to African, Asian countries”, Xinhua Net, 11 January 2022, https://english.news.cn/20220111/af07d427503b4070a4afa48afb619f49/c.html

[4] “Chinese debt casts shadow over Maldives’ economy”, The Economic Times, 17 September 2020, https://m.economictimes.com/news/international/world-news/chinese-debt-casts-shadow-over-maldives-economy/articleshow/78172615.cms.

[5] The Rubber-Rice Pact was signed between China and Ceylon in December 1952. China needed to import rubber and other supplies from Ceylon. In turn, Ceylon was facing rising price of rice and needed more import.

[6] “Explained: The Colombo port setback for India”, The Indian Express, 4 February 2021, https://indianexpress.com/article/explained/colombo-port-india-sri-lanka-7173610/.

[7] Zheng Haiqi, “Why Chinese Diplomacy focus on Indian Ocean Island States”, Xinmin, 12 January 2022, https://wap.xinmin.cn/content/32096531.htm

[8] Ministry of Foreign Affairs, People’s Republic of China, “Remarks by H.E. Wang Yi at the Opening Ceremony of The Session of the Council of Foreign Ministers of the Organization of Islamic Cooperation”, 22 March 2022, https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/wjb_663304/wjbz_663308/2461_663310/202203/t202203%2023_10654638.html

[9] For the Chinese perspective on revocation of Article 370, see Ren Yuanzhe, “Article 370: A Chinese Perspective”, Institute of South Asian Studies (ISAS) Brief No. 687, 8 August 2019, https://www.isas.nus.edu.sg/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/ISAS-Briefs-687_Ren-Yuanzhe.pdf.

[10] Claudia Chia and John Joseph Vater, “Six Months On: China and Taliban 2.0”, ISAS Insights No. 710, 8 March 2022, https://www.isas.nus.edu.sg/papers/six-months-on-china-and-taliban-2-0/.

[11] Ministry of Foreign Affairs, People’s Republic of China, “Wang Yi Holds Talks with Acting Deputy Prime Minister of Afghan Interim Government Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar”, 24 March 2022, https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/wjb_663304/wjbz_663308/activities_663312/202203/t20220325_10655539.html.

[12] Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, “Wang Yi Talks about Diplomatic Recognition of the Afghan Interim Government”, 1 April 2022, https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/zxxx_662805/%20202204/t20220401_10662740.html.

[13] Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, “The Tunxi Initiative of the Neighboring Countries of Afghanistan on Supporting Economic Reconstruction in and Practical Cooperation with Afghanistan”, 1 April 2022, https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/eng/zxxx_662805/202204/t20220401_106%2062024.html.

[14] Tanvi Madan, Major Power Rivalry in South Asia, Council on Foreign Relations, October 2021, p. 3.

[15] “India approves investments worth $1.79 billion from its neighbours”, Reuters, 16 March 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/india/india-approves-investments-worth-179-billion-its-neighbours-2022-03-16/.

[16] C. Raja Mohan, “India-China Relations: Getting Beyond the ‘Abnormal’,” Institute of South Asian Studies (ISAS) Brief No. 917, 29 March 2022, https://www.isas.nus.edu.sg/papers/india-china-relations-getting-beyond-the-abnormal/.

[17] Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, “Official Spokesperson’s response to media queries on reference to Union Territory of Jammu & Kashmir made by Chinese Foreign Minister in his speech to Organisation of Islamic Cooperation in Pakistan”, 23 March 2022, https://mea.gov.in/response-to-queries.htm?dtl/35018/Official_Spokespersons_response_to_media_queries_on_reference_to_Union_Territory_of_Jammu__Kashmir_made_by_Chinese_Foreign_Minister_in_his_speech_to_O.

[18] “China does not seek ‘unipolar Asia’, respects India’s role in region, says foreign minister”, Reuters, 25 March 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/china/china-does-not-seek-unipolar-asia-respects-indias-role-region-says-foreign-2022-03-25/.

[19] “Will Nepal’s new ‘pro-India’ prime minister hit reset on its China ties?”, South China Morning Post, 21 July 2021, https://www.scmp.com/week-asia/politics/article/3142000/will-nepals-new-pro-india-prime-minister-hit-reset-its-china.

[20] “Yearender: Nepal-China cooperation moves ahead amid COVID-19 pandemic”, Xinhua Net, 23 December 2021, http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/20211223/500bd41750c0488f8775439ff85fde69/c.html.

[21] Amit Ranjan, “Wang Yi’s Visit to Nepal: A Boost to Bilateral Ties,” ISAS Brief No. 918, 29 March 2022, https://www.isas.nus.edu.sg/papers/wang-yis-visit-to-nepal-a-boost-to-bilateral-ties/.

[22] Amit Ranjan, “Chinese Aid to the South Asian Countries at the time of COVID-19 Pandemic: Norms or for Political gains?” Contemporary Chinese Political Economy and Strategic Relations, Volume 7 Number 3 (December 2021): pp. 1521-1550 ; and Deep Pal, “China’s Influence in South Asia: Vulnerabilities and Resilience in Four Countries,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 13 October 2021, https://carnegieendowment.org/2021/10/13/china-s-influence-in-south-asia-vulnerabilities-and-resilience-in-four-countries-pub-85552

Photo credit: Lijian Zhao’s Twitter

-

More From :

More From :

-

Tags :

Tags :

-

Download PDF

Download PDF