Summary

Nestled between India and China, Bhutan has been walking a tightrope in dealing with the two Asian powers. While country is politically close to New Delhi, Beijing does not have diplomatic residence in Thimphu. In October 2021, Bhutan and China signed a memorandum of understanding to expedite border negotiation. This paper analyses the boundary issues between the two countries and Thimphu-Beijing engagements. It also examines India’s concerns in this regard.

Introduction

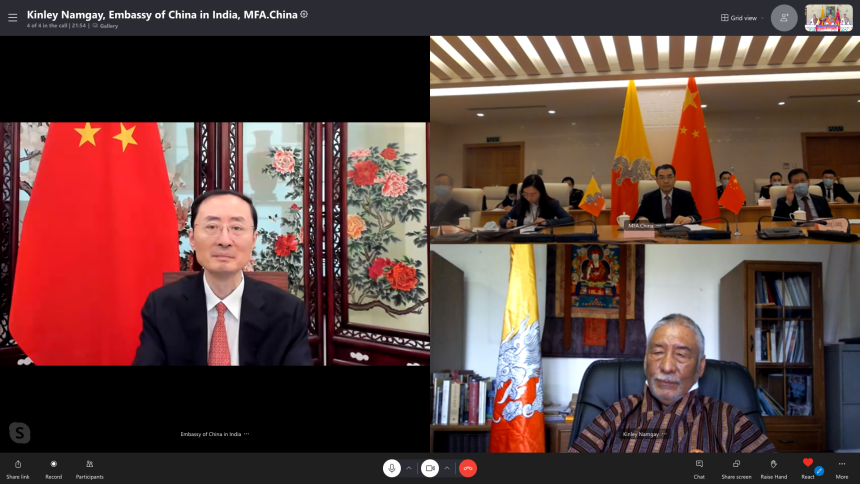

On 14 October 2021, Thimphu and Beijing signed a memorandum of understanding (MoU) on three-step roadmap for “Expediting the China-Bhutan Boundary Negotiation” via a video link conference. China was represented by Assistant Foreign Minister Wu Jianghao while Bhutan’s Foreign Minister Tandi Dorji signed the agreement on behalf of his country.[1] The roadmap for the MoU was earlier finalised during the 10th round of the Expert Group meeting in Kunming in April 2021 and was presented for approval by the respective governments.[2] In the past 37 years, Bhutan and China have held 24 rounds of talks and 10 expert group level meetings.[3]

Hailing the MoU, the Chinese media, CGTN, wrote, “At a time when India is pursuing hegemony by coercion over its neighbours, the MoU is a victory for the region. It demonstrates that respectable, bilateral diplomacy has triumphed over New Delhi’s attempts to dominate, control and bully its neighbours, showing India has little ability to regionally isolate China.”[4] Quoting from the Global Times, the CGTN note added, “The territorial disputes between China and Bhutan are not huge, but have not been resolved…It is India that stands in the way as the country has a special cultural influence on Bhutan historically, and an impact on Bhutan in defence and diplomacy.”[5] While showing the MoU as a “disaster” for New Delhi, the Chinese media “underscored” their ignorance of ground realities.[6] Like in the past, it is possible that the Indian government was kept in the loop about the MoU. While Ashok Kantha, former Indian Ambassador to China and Director of the Institute of Chinese Studies, New Delhi, said, “There’s nothing particularly shady about this MoU”,[7] during the weekly interaction with media persons, Arindam Bagchi, official spokesperson of the Indian Ministry of External Affairs, said, “We have noted the signing of the memorandum of understanding between Bhutan and China…we are aware of it.”[8]

Bhutan-China Border Issues

Across the world, 50 per cent of wars between 1816 and 1992 had occurred due to disputed territories.[9] Territorial disputes exist for several reasons – first, disagreement on legal validity of a treaty signed under duress or by the third party; second, when a coloniser or third party cedes control of some tract of territory, which is claimed by more than one newly independent state; third, discovery of new geological data showing the actual territorial markers that were noted in a boundary treaty, but never actually cited; and lastly, territorial claims can be initiated to gain bargaining leverage against a target state.[10] Many of the territorial conflicts result from the importance of territory for economic, political, historical and ethnic reasons. The value of territory decides when the states will fight and when they are ready to dissolve their differences in peaceful ways.[11] Huth (1996)[12] analyses three stages of territorial disputes. First, the policymakers decide whether to confront their neighbour with competing claims or accept the status quo. Second, the states which are embroiled in territorial disputes apply diplomatic and military pressure to resolve disputes in their favour. Third, the challenger state largely seeks peaceful resolution to territorial disputes. For example, of the 129 cases of territorial disputes between 1950 and 1990, 53 (41 per cent) were settled peacefully, 57 (about 44 per cent) cases were in stalemate and the remaining 19 cases (15 per cent) were settled by occupation of disputed territory or “capitulation by target in signed agreement”.[13] Linked to territory, border related disputes are primarily due to differences and disagreements over demarcation of the boundary line between the sovereign states. Border demarcation issue often causes disputes, but it is not an adequate reason. For example, there are many African countries between whom the border is not demarcated for various reasons; however, they are not in dispute.[14] Hence, border demarcation is one of the many reasons for disputes which border sharing countries raise at politically appropriate time.

China and Bhutan share about 477 kilometres of border. China lays claim on Jakarlung and Pasamlung in central Bhutan and Doklam, Sinchulung, Dramana and Shakhatoe in western Bhutan.[15] To address their territorial issues, Bhutan considered direct negotiations with China in 1979.[16] However, it took five years for the two countries to come to the negotiation table. The first boundary talks took place in 1984.[17] In 1997, China put forward a “package deal” with Bhutan where it agreed to give up claims on areas in central Bhutan (Pasamlung and Jakarlung valleys) in return for western Bhutan (Doklam, Sinchulung, Dramana and Shakhatoe).[18] Bhutan and China came close to sealing the deal in 2001 but Thimphu backed off after India’s conviction, citing security reasons.[19] Despite engagement in talks, in 2017, China started road construction near Doklam. Bhutan accused China of unilaterally attempting to change the status quo in Doklam region.[20] In its 29 June 2017 press release, the government of Bhutan stated:

“[W]e [Bhutan and China] have written agreements of 1988 and 1998 stating that the two sides agree to maintain peace and tranquillity in their border areas pending a final settlement on the boundary question, and to maintain status quo on the boundary as before March 1959… Bhutan has conveyed to the Chinese side, both on the ground and through the diplomatic channel, that the construction of the road inside Bhutanese territory is a direct violation of the agreements and affects the process of demarcating the boundary between our two countries.” [21]

Construction work, although objected by Bhutan, nevertheless, continued. It caused a 73-day military stand-off between the Indian Army and China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA) troops. On Bhutan’s stand on the Sino-India military stand-off at Doklam, Tenzing Lamsang, editor of The Bhutanese, wrote:

“At the beginning of the standoff one assumption made by some commentators and media outlets was that of Bhutan being almost an Indian ‘protectorate’ and that it would do whatever India wanted.

The assumption on the other side was that Bhutan would be intimidated by China, and like it had done in past border encroachments, it could ride roughshod over Bhutan on the issue to build roads where it wants.

By the end of the standoff both assumptions were turned on its head by Bhutan with its public statements, as well as behind the scenes diplomacy with both countries, helping them to not only achieve the disengagement, but also drawing red lines for both sides.” [22]

At that time, Thimphu refused to send its soldiers to join the Indian army and face the Chinese soldiers. “Bhutan also chose to neither confirm nor deny that it had invited Indian troops into Doklam.”[23]

After Doklam, in June 2020, amid the COVID-19 pandemic, during the virtual meeting of the Global Environment Facility, China raised its claim on Sakteng Wildlife Sanctuary in Trashigang district.[24] This was a new territorial claim by China. The Chinese map of 1977 shows Sakteng within Bhutan even when it claims the Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh. Even the Chinese map of 2014 excluded Sakteng.[25] Hence, it seems that the growing tensions with India has resulted in Beijing making new claims on eastern Bhutan. Sakteng is near Arunachal Pradesh.

Further, in November 2020, there were news reports about China setting up Pangda village in Bhutanese territory.[26] This was, however, denied by both Bhutan and China.

India’s Concerns

On 1 January 2022, China’s Land Border Law (LBL) came into effect. It “stipulates that the sovereignty and territorial integrity of the People’s Republic of China are sacred and inviolable”.[27] It calls on the state to take “measures to resolutely safeguard territorial integrity and land border security, and guard against and combat any acts that undermine territorial sovereignty and land boundaries”.[28] The LBL clarifies the government’s responsibilities and military tasks in territorial border work, the delineation and surveying of land borders, the defence and management of land borders and frontiers, and the international cooperation on land border affairs. The LBL asks the citizens and organisations in the border region to support border patrol and control their activities.[29] The LBL stipulates that physical violence, coercion or even weapons can be used against anyone found crossing the border illegally. It regulates the national and regional governments to take measures to protect the stability of cross-border rivers and lakes, and rationally use the water resources. Vessels and personnel will be inspected and must get approval from relevant authorities before entering the rivers and lakes.[30] Finally, the LBL underlines that China follows the principle of equality, mutual trust and friendly consultation; it handles land border related affairs with neighbouring countries through negotiations to properly resolve disputes and longstanding border issues.[31]

With the LBL in effect, it is expected that Chinese are not likely to give up or dilute their claims on Indian territories or in any other country. The LBL, as Gautam Bambawale, former Indian Ambassador to China, observes, indicates that the Chinese are, it seems, “tired of trying to resolve the boundary or the LAC [Line of Actual Control] through negotiations; they are indicating they’ll do it through use of force.”[32]

In the case of the China-Bhutan border issues, some of the Chinese territorial claims are closer to the areas which are of strategic significance to India. For example, Doklam is near India’s strategic “Chicken Neck” corridor which is the only land link to India’s Northeast from other parts of the country.[33] Due to stand-off in 2017, the road to Zompelri ridge near Doklam could not be extended. The area around Zompelri ridge is patrolled by the Bhutanese Army.[34] Also, the Indian Army occupies an advantageous position in the ridge area.[35] However, a recent report published by Reuters stated that China has accelerated settlement-building work along its border with Bhutan which is 9 to 27 kilometres from the Doklam.[36]

Conclusion

Border demarcation is not an adequate reason for China to engage with Bhutan. The political rift with India, escalating military tensions at the Sino-India LAC and India’s closeness to the United States, Japan and Australia are driving forces for the Chinese to push Bhutan to settle their boundary issues. Through Bhutan, China is aiming at India.

There is a wide perception in India that Bhutan could be “pushed” or “arm twisted” by China to attain a favourable deal on border issues. Besides, after the resolution of the border, Beijing may successfully persuade Thimphu to allow it to set up a diplomatic residence in Bhutan and open the country to Chinese investments and tourists.

It is believed that Bhutan keeps the Indian government in the loop about its talks with China and would not sign any document harmful to India’s interests. However, worries remain for India.

. . . . .

Dr Amit Ranjan is a Research Fellow at the Institute of South Asian Studies (ISAS), an autonomous research institute at the National University of Singapore (NUS). He can be contacted at isasar@nus.edu.sg. The author bears full responsibility for the facts cited and opinions expressed in this paper.

Photo credit: Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Bhutan (https://www.mfa.gov.bt/?p=11456)

[1] Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, “China and Bhutan Sign MoU on a Three-Step Roadmap for Expediting the China-Bhutan Boundary Negotiation”, https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/ mfa_eng/wjb_663304/zygy_663314/gyhd_663338/202110/t20211016_9550700.html. Accessed on 6 January 2022.

[2] Suhasini Haider, “Bhutan, China sign MoU for 3-step roadmap to expedite boundary talks”, The Hindu, 14 October 2021, https://www.thehindu.com/news/international/bhutan-and-china-sign-mou-for-3-step-roadmap-to-expedite-boundary-talks/article36999596.ece. Accessed on 8 January 2022.

[3] Ibid.

[4] “China-Bhutan MoU a victory over India’s pursuit of South Asia hegemony”, CGTN , 15 October 2021. https://news.cgtn.com/news/2021-10-15/China-Bhutan-MoU-a-victory-over-India-s-pursuit-of-South-Asia-hegemony-14nxsPb7SDu/index.html. Accessed on 8 January 2022.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Harsh V Pant and Aditya Gowdara Shivmurthy ‘Threat and Perceptions in the Himalayas: The complexity of Bhutan’, Observer Research Foundation, 5 November 2021, https://www.orfonline.org/research/the-complexity-of-bhutan/. Accessed on 8 January 2022.

[7] “Tawang’s linkages with Bhutan”, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4J29K4DtdMQ. Accessed on 8 January 2022; and Pia Krishnankutty, “China may push Bhutan for ‘definitive response’ on border dispute: Ex-envoy Nambiar on MoU”, The Print, 20 October 2021, https://theprint.in/diplomacy/china-may-push-bhutan-for-definitive-response-on-border-dispute-ex-envoy-nambiar-on-mou/753920/. Accessed on 8 January 2022.

[8] Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, “Transcript of Weekly Media Briefing by the Official Spokesperson (October 14, 2021)”, 14 October 2021, https://mea.gov.in/media-briefings.htm?dtl/34394/ Transcript+of+Weekly+Media+Briefing+by+the+Official+Spokesperson+October+14+2021. Accessed on 6 January 2022.

[9] Francesco Mancini, “Uncertain Borders: Territorial Disputes in Asia”, ISPI Analysis No. 180. p. 2, 1 June 2013.

[10] Krista E Weigand, Enduring Territorial Disputes: Strategies of Bargaining, Coercive Diplomacy, and Settlement (Georgia: University of Georgia Press, 2011) pp. 9-11.

[11] Paul Diehl and Gary Goertz, Territorial Changes and International Conflict, (London: Routledge, 1992) p. 14.

[12] Paul K Huth, Standing Your Ground: Territorial Disputes and International Conflict, (Michigan: University of Michigan Press, 1996, Reprint 2009).

[13] Ibid., p. 141.

[14] Ibid., p 26.

[15] Manoj Joshi, “In China’s Territorial Claims in Eastern Bhutan, a massage for India?”, The Wire, 10 July 2020, https://thewire.in/external-affairs/china-bhutan-india-territory. Accessed on 11 July 2020.

[16] Amit Ranjan, “China’s New Claim in Eastern Bhutan: Pressure Tactic or Message to India?”, Insights No. 629 Institute of South Asian Studies, 20 July 2020, https://www.isas.nus.edu.sg/papers/chinas-new-claim-in-eastern-bhutan-pressure-tactic-or-message-to-india/. Accessed on 25 December 2020.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Raj Chengappa and Ananth Krishnan, “India-China standoff: All you need to know about Doklam dispute”, India Today, 7 July 2017, https://www.indiatoday.in/magazine/cover-story/story/20170717-india-china-bhutan-border-dispute-doklam-beijing-siliguri-corridor-1022690-2017-07-07. Accessed on 4 January 2021.

[21] Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Royal Government of Bhutan, “Press Release”, 29 June 2017, https://www.mfa.gov.bt/?p=4799. Accessed on 10 January 2022.

[22] Tenzing Lamsang “Bhutan’s diplomatic triumph in Doklam”, The Bhutanese, 2 September 2017, https://thebhutanese.bt/bhutans-diplomatic-triumph-in-doklam/. Accessed on 6 January 2022.

[23] Nitasha Kaul, “Beyond India and China: Bhutan as a Small State in International Relations”, International Relations of the Asia-Pacific, lcab010, p. 21, 23 July 2021, https://doi.org/10.1093/irap/lcab010.

[24] “After India, China Lays Claim on Bhutan Territory, Calls Trashigang District Border ‘Disputed Area’”, India.com, 30 June 2020, https://www.india.com/news/india/after-india-china-lays-claim-on-bhutan-territory-calls-trashigang-district-border-disputed-area-4071780/ Accessed on 4 January 2021.

[25] Tenzing Lamsang on Twitter, https://twitter.com/tenzinglamsang/status/1331847176276774918.

[26] “‘No Chinese Village Within Territory,’ Says Bhutan After China Journalist Tweets, Deletes Claim”, The Wire, 20 November 2020, https://thewire.in/external-affairs/china-bhutan-village-cgtn-pangda-new-delhi. Accessed on 20 December 2020.

[27] Huang Lanian and Yan Yuzhu, “China adopts land borders law amid regional tensions, vowing to better protect territorial integrity at legal level”, Global Times, 24 October 2021, https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202110/1237171.shtml. Accessed on 7 January 2021.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Ibid.

[30] Ibid.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Krishn Kaushik, “Explained: China’s new land border law and Indian concerns”, The Indian Express, 27 October 2021, https://indianexpress.com/article/explained/chinas-new-land-border-law-indian-concerns-7592418/. Accessed on 7 January 2022.

[33] “Where is Doklam and why it is important for India?”, India Today, 27 March 2018, https://www.indiatoday.in/education-today/gk-current-affairs/story/where-doklam-why-important-india-china-bhutan-1198730-2018-03-27. Accessed on 8 January 2022.

[34] Tenzing Lamsang on Twitter https://twitter.com/tenzinglamsang/status/1331186878255566849.

[35] Manoj Joshi, “The China-Bhutan border deal should worry India” Observer Research Foundation, 22 October 2021. https://www.orfonline.org/research/the-china-bhutan-border-deal-should-worry-india/. Accessed on 7 January 2022.

[36] Devjot Ghoshal and Anand Katakam “China steps up construction along disputed Bhutan border, satellite images show”, Reuters, 13 January 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/china/china-steps-up-construction-along-disputed-bhutan-border-satellite-images-show-2022-01-12/. Accessed on 13 January 2022.

-

More From :

More From :

-

Tags :

Tags :

-

Download PDF

Download PDF