Bangladesh’s FTA with Singapore: A Stepping Stone Towards the ASEAN Market

Mohammad Masudur Rahman, Divya Murali

13 September 2021Summary

Bangladesh’s strong trade links with Singapore and the urge to locate new markets with preferential access make Singapore an ideal partner for negotiating a free trade agreement (FTA). An FTA with Singapore will provide Bangladesh preferential access to the entire Southeast Asian and Asia Pacific regions. For Singapore, the FTA would be the third with a South Asian country – after India and Sri Lanka – and will help to strengthen its market penetration in South Asia. A clear understanding of the economic impact of FTAs is key for Bangladesh particularly after it graduates from Least Developed Countries category in 2026. Coordination among different ministries and departments will play a critical role for Bangladesh where differing views are prominent among different ministries. As Singapore is an experienced FTA partner, Bangladesh will find in it a good supporting mentor for its future FTA negotiations roadmap. An FTA with Singapore will not only ensure market access for both goods and services but will also reflect Bangladesh’s positive image and competitiveness globally to attract foreign direct investment.

Introduction

Bangladesh is one of the fastest-growing emerging economies and the second-largest garments exporter in the world. It has made remarkable progress over the last 50 years particularly on its socio-economic front propelled by its growing trade and role in global supply chain. Singapore is at the heart of the global supply chain and a core member of many bilateral and regional free trade agreements (FTAs), including the Association of Southeast Asian Nations FTA, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) and the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership, among others. Notwithstanding the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, Singapore is Bangladesh’s third-largest import partner and Bangladesh is Singapore’s second-largest trading partner in South Asia,[1] which is a testament to the strong bilateral trade ties the two countries share. While Bangladesh will graduate from the Least Developed Countries (LDC) status in 2026, an FTA with Singapore will ensure its sustainable market access in the East Asian region and could stand to potentially benefit both the countries.

Bilateral Trade

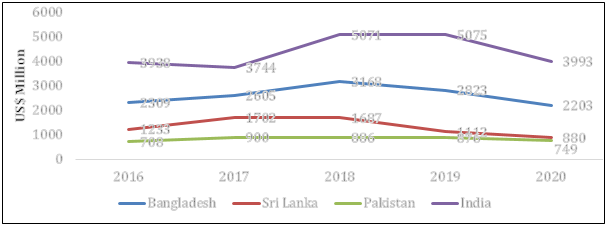

Bangladesh is one of the leading emerging economies that has been a frontrunner in South Asia, with a steady average economic growth rate of about 6.5 per cent over the last decade and has managed to maintain a growth rate of five per cent during the pandemic.[2] Singapore is a proponent of free trade and plays a vital role in global supply chain. The country is also the third-largest importing partner of Bangladesh accounting for about US$2.4 billion (S$3.23 billion) in 2020 even amidst the pandemic (Table 1). Singapore’s trade surplus with Bangladesh was about US$2.2 billion (S$2.96 billion) while with India, a much larger economy and a neighbour of Bangladesh, was about US$3.9 billion (S$5.24 billion) in 2020. This indicates Bangladesh is one of Singapore’s important trading partners in South Asia (Figure 1). It is worthwhile to mention that Singapore’s trade surplus with Pakistan and Sri Lanka – the other major South Asian economies – is much lower compared to Bangladesh.

Figure 1: Singapore’s Trade Surplus with South Asian Countries

Source: Trade Map (2021); https://www.trademap.org/Index.aspx.

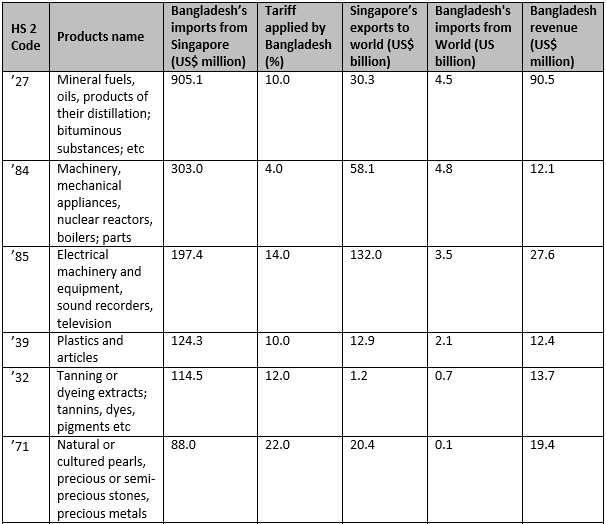

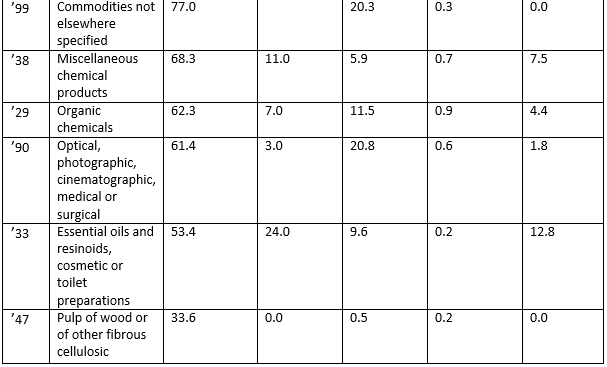

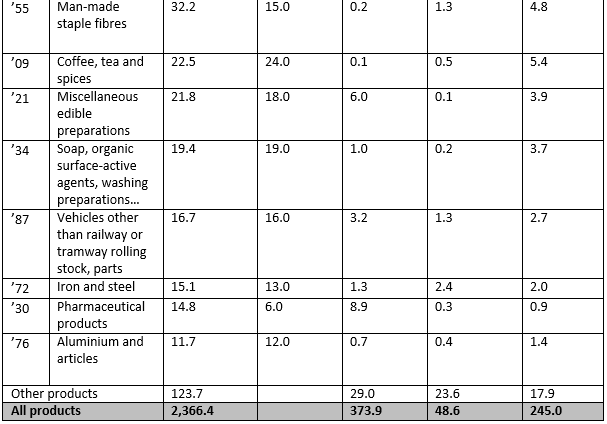

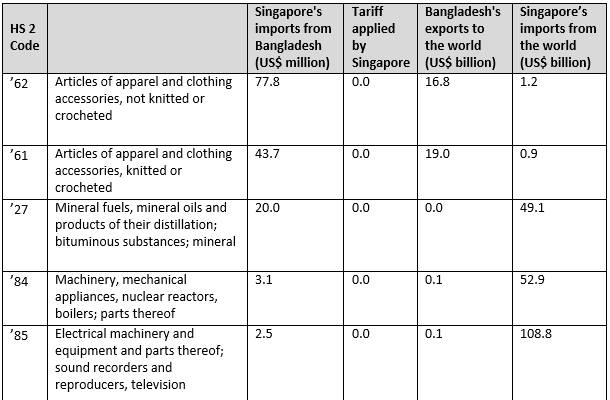

The import-export structure of Bangladesh and Singapore are different yet complementary to each other. Overall, Bangladesh’s main imports are petroleum oils and minerals, precious metal, sewing machines, communication apparatus, wood pulp, chemical, electric generating sets, petroleum gases, etc., which are mostly capital and intermediate capital products (Table 1).

From Singapore, Bangladesh imports capital machinery and intermediate goods and exports mostly garment products. Bangladesh’s total import of capital machineries and intermediates goods from the world amounted to approximately US$13 billion (S$17.47 billion) in 2020 and Singapore’s exports of the same to the world during 2020 was about US$220 billion (S$295.64 billion). However, Bangladesh only imported about US$1.4 billion (S$1.88 billion) worth of capital and intermediate goods from Singapore (Table 1).[3] Similarly, Singapore imported over US$3 billion (S$4.03 billion) garment products from the world in 2020 while Bangladesh’s export of garments to the world was over US$35 billion (S$47.03 billion). However, Bangladesh garment products exports to Singapore was less than US$200 million (S$268.76 million) in 2020 (Table 2).[4] This shows that both Bangladesh and Singapore have excellent scope to increase their primary exports to each other and an FTA might give this a push forward.

Table 1: Bangladesh’s Imports from Singapore in 2020

Source: Trade-Map (2021) accessed on 17 August 2021; https://www.trademap.org/Index.aspx.

Table 2: Singapore’s Imports from Bangladesh in 2020

Source: Trade-Map (2021) accessed on 17 August 2021; https://www.trademap.org/Index.aspx.

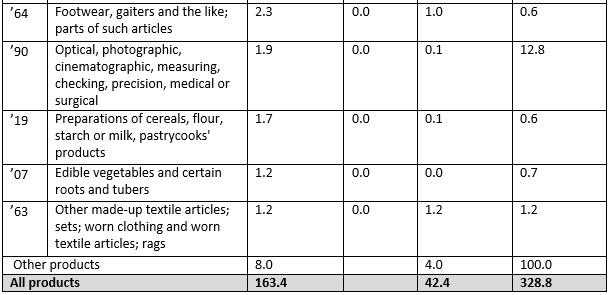

A general point to note is that an FTA will result in some revenue loss in the short run. However, in the long run, it will prove beneficial to an economy. When Bangladesh enters into an FTA with Singapore and eliminates its import duties for products from Singapore, it will lead to a revenue loss of about US$245 million (S$329.23 million) for Bangladesh (Table 1). However, the larger benefit to its economy will outweigh this temporary revenue loss as tariff elimination would boost the country’s industrial productivity, lowering production costs and making it competitive globally. Internal resources mobilisation is fundamental in this scenario for sustainable economic growth. Bangladesh has reduced its tariff structure over the decade and the weighted average of applied tariff is about nine per cent (Figure 2). However, there is scope to lower them further as currently the maximum tariff level is 25 per cent.

Singapore has been a model state for implementing trade facilitation agreements of the World Trade Organization. It has fully implemented digital national single window clearance system and other trade facilitation arrangements.[5] Bangladesh can tap on Singapore’s expertise to get technical support in this regard and build capacities. However, the potential FTA between the two countries might encounter could encounter challenges on the issues of non-tariff measures, trade facilitation and simplified rules of origin. Thus, as Bangladesh graduates from LDC in 2026, it would serve the country well if its domestic trade policy rules are streamlined by then.

Figure 2: Weighted average applied tariff of Bangladesh and Singapore (%)

Source: World Bank (2021).

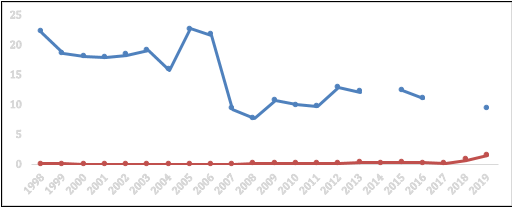

Potential Impact of Bangladesh Singapore FTA on Goods[6]

In trying to understand the impact of an FTA, a computable general equilibrium model was run. The results show that economic welfare for Singapore may increase about US$100 million (S$134.38 million). For Bangladesh, economic welfare loss is minuscule which is about US$2 million (S$2.69 million). The FTA may have a positive impact on Singapore’s gross domestic product (GDP [0.002 per cent]). The simulation shows a miniscule negative impact on Bangladesh GDP (0.001 per cent) due to loss of some tariff revenue. It is worthwhile to note that Bangladesh imposes about 10 per cent duty for imports from Singapore while Singapore’s import tariff is almost zero. However, export and imports will increase for both partners which indicates that trade will improve between two countries.

Figure 3: Macroeconomic Impact of Bangladesh Singapore FTA on goods:

Source: Author’s simulations.

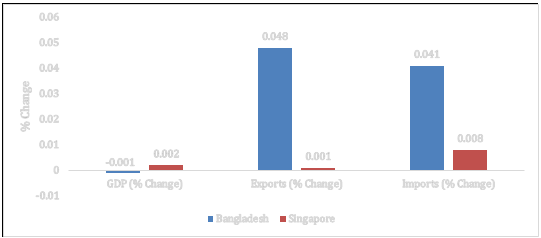

Trade in Services

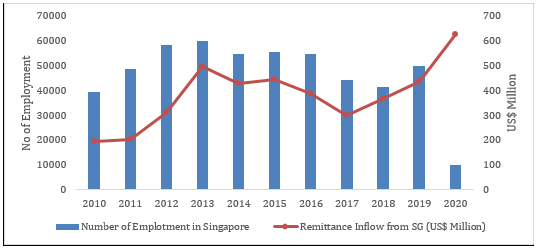

Trade in services is likely to be a top agenda for Bangladesh while negotiating an FTA with Singapore. There is a large Bangladeshi diaspora and semi-skilled labour living in Singapore, Malaysia, Korea and Japan. This is one of the main sources of remittance inflow for the country. An FTA with Singapore would be an important channel for Bangladesh to access East Asia and the RCEP market for goods and services. Bangladesh received US$624 million (S$838.53 million) in remittances in 2020 from its large diaspora in Singapore which is three times higher than its export value. Bangladesh sends about 50,000 people to Singapore every year but in 2020 it fell to only 10,000 which may become a new normal in the future (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Employment and remittance inflow from Singapore

Authors’ calculation from Bangladesh Bank data 2021 and Bureau of Manpower, Employment and Training (BMET) (2021).

Singapore’s Investment in Bangladesh

Singaporeans are interested in Bangladesh’s rapid growth. Singapore is one of the top investors in power, energy, transport, logistics and ports in the country. In addition, a market of 170 million people in the services sector should be an attractive investment destination. In 2018, Bangladesh’s Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina visited Singapore and offered a Special Economic Zone (SEZ) for Singapore investors,[7] which was a remarkable step to increase bilateral trade and investment cooperation. Singapore is yet to take up this offer, while Japan, Korea, China and even India have accepted the offer and invested heavily in their respective SEZ areas.

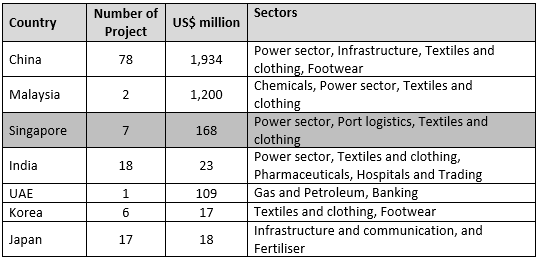

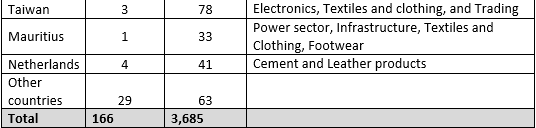

Bangladesh has established 98 SEZs[8] and 12 high-technology industrial park[9] for long-term sustainable industrial development. Many different types of incentives are offered to both domestic and foreign investors in the SEZs. Japanese, Korean, Indian and Chinese SEZs have been established to increase product diversification and cluster development for industrialisation. This is a huge impetus for Bangladesh’s industrialisation aspiration. The Chinese Economic and Industrial Zone, Indian Economic Zone (Mongla), Japanese Economic Zone (Araihazar) are top investors in these SEZs. According to the Bangladesh Investment Development Authority (2020), China registered 78 new projects among 166 total projects in 2020 which amounted to about US$2 billion (S$2.69 billion) and accounted for more than 50 per cent of total investment in Bangladesh. Apart from China, Japan is another major investor with two major projects implemented – elevated express railway in Dhaka and Matabari deep seaport.

Table 3: Bangladesh Foreign Investment in FY 2019-2020

Source: Bangladesh Investment Development Authority (2020) and Bangladesh Bank (2021).

Conclusion

Bangladesh is set to move into a new phase of growth and development. Most of the mega projects will be completed within the next few years and when these become operational, the country will become a new hub in the regional supply chain. An FTA with Singapore at this juncture – which is the third top investor in Bangladesh – could be that critical partnership that Dhaka might need to sustain its economic growth story.

. . . . .

Dr Mohammad Masudur Rahman is a Visiting Research Fellow at the Institute of South Asian Studies (ISAS), an autonomous research institute at the National University of Singapore. He can be contacted at masudrahman@nus.edu.sg. Ms Divya Murali is a Research Analyst at the same institute. She can be contacted at divya.m@nus.edu.sg. The authors bear full responsibility for the facts cited and opinions expressed in this paper.

Photo credit: Facebook/Dhaka Chamber of Commerce and Industry.

[1] Yong Hui Ting, “Singapore, Bangladesh urged to collaborate on enhancing connectivity”, The Business Times, 25 June 2021, https://www.businesstimes.com.sg/government-economy/singapore-bangladesh-urged-to-collaborate-on-enhancing-connectivity.

[2] Extracted from Bangladesh GDP annual growth rate, Tradingeconomics.com; https://tradingeconomics. com/bangladesh/gdp-growth-annual

[3] HS code ’27, ’84 and ’85 of Table 1.

[4] HS digit ’61, ’62 and ’63 of Table 2.

[5] Trade Intelligence and Negotiation Adviser (TINA), https://tina.trade. Accessed on 6 September 2021.

[6] The GTAP version 10 database has used for this simulation. A comparative static MyGTAP model which is an extension of GTAP model has used for this simulation (Rahman, 2021).

[7] Nur Asyiqin Mohamad Salleh, “Bangladeshi PM woos Singapore companies with economic and land incentives”, The Straits Times, 13 March 2018, https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/manpower/ bangladeshi-pm-woos-singapore-companies-with-economic-and-land-incentives.

[8] Economic Zone Sites, Bangladesh Economic Zones Authority (BEZA), https://www.beza.gov.bd/economic-zones-site/.

[9] Project Location Map, Bangladesh Hi-Tech Park Authority, http://bhtpa.gov.bd/.

-

More From :

More From :

-

Tags :

Tags :

-

Download PDF

Download PDF