Abrogation of Article 370:

An Analysis of the Supreme Court Verdict

Imran Ahmed, Muhammad Saad Ul Haque

13 January 2024Summary

Despite the anticipation of a reversal, the Supreme Court of India upheld the constitutional validity of the abrogation of Article 370, leading to a continued divide in public opinion. This paper discusses the court’s recent verdict and covers the historical context, challenges to constitutional changes, the Supreme Court’s rationale and the ongoing repercussions of the abrogation, including media crackdowns, human rights concerns and political developments.

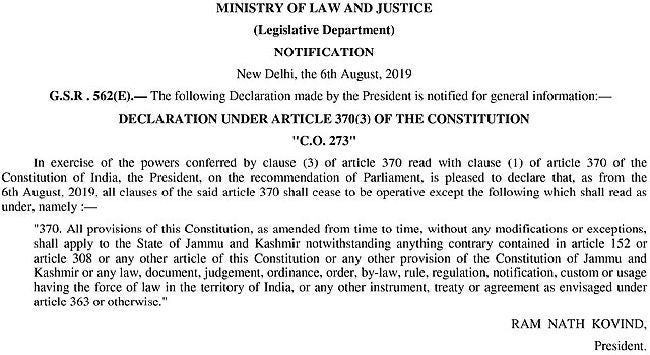

On 11 December 2023, the Supreme Court of India upheld the Narendra Modi government’s 2019 decision to revoke Article 370 which provided special arrangements for the governance of the state of Jammu and Kashmir. Issuing Constitutional Orders (CO) 272 and 273 during a Proclamation under Article 356(1)(b), India’s President Droupadi Murmu extended the entire Indian constitution to Jammu and Kashmir, repealing Article 370. Concurrently, the Indian parliament enacted the Jammu and Kashmir Reorganisation Act 2019, bifurcating the state into two union territories subject to the direct oversight of the central government. The bench, consisting of Chief Justice D Y Chandrachud and Justices Sanjay Kishan Kaul, Sanjiv Khanna, B R Gavai and Surya Kant adjudged the constitutionality of these actions.

The origins of Article 370 can be traced back to the partition of the British Raj (rule) in 1947 when the princely states of India were given a choice to either accede to Pakistan or India. Hari Singh, the Hindu ruler of the majority Muslim state of Jammu and Kashmir, would eventually ratify an instrument of accession to India. Initially, the various princely states of India were allowed to have a separate constitution, but in 1949, the rulers and chief ministers of the states agreed to accept the constitution of India for their own states. The state of Jammu and Kashmir, however, rejected this, and, instead in 1950, Article 370 came into force giving special status to the state limiting central government control.

Despite the provisions included in Article 370, there have been several presidential orders over the years that India has used to increase its reach and control in the state. Nonetheless, Article 370 was symbolically important for many living in Jammu and Kashmir. The state having its own constitution and flag allowed the people to hold on to a unique cultural and linguistic identity. Consequently, the revocation of Article 370 was perceived by many Kashmiris as an assault on their national identity.

Alongside the public outcry, petitions from various parties were filed before the court following the proclamation of the abrogation of Article 370. There were two main arguments within these petitions: one challenging the constitutionality of the presidential orders and the second the bifurcation of the former state of Jammu and Kashmir into two union territories. Petitioners argued that the president was bound by the Indian constitution, and thus unable to abrogate the special status of Article 370 without the permission of the constituent assembly. Whether Article 367 of the constitution can be used to amend the meaning of ‘constituent assembly’ to mean ‘legislative assembly’ was a central issue in the case.

The revocation of Kashmir’s special status was a long-term goal of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). According to the election manifesto of 2019, the party stated, “We reiterate our position since the time of the Jan Sangh to the abrogation of Article 370”. The origins of the BJP lie with the Jan Sangh Party, indicating that the BJP’s position on Article 370 and Kashmir has remained steadfast on its agenda since the party’s birth.

Nearly four and a half years after the abrogation of Article 370, the people of Jammu and Kashmir continue to experience its repercussions. The crackdown on press freedom has been unparalleled with numerous arrests under the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act (UAPA), enabling the state to designate suspects as ‘terrorists’ without producing incriminating evidence. The strict requirements for bail under the law have resulted in individuals spending months, and often many years, in jail without a guilty verdict. Moreover, the government’s crackdown on dissent using the UAPA led to a 37 per cent increase in arrests in 2019 compared to the previous year, according to India’s National Crime Records Bureau.

On the political front, Kashmir has not seen an assembly election since 2014. In 2015, a coalition government was formed by the BJP and Mehbooba Mufti’s Peoples Democratic Party (PDP). However, when the BJP withdrew its support for the PDP, the government collapsed. Kashmir has since been governed by the central government by proxy of a hand-picked Lieutenant Governor. The court established 30 September 2024 as the deadline for conducting assembly elections in the now newly designated union territories.

While many Kashmiris were waiting for the possibility that the Supreme Court would reverse the presidential order of 2019, the bench comprising India’s five most senior Supreme Court judges unanimously agreed that Article 370 was always a temporary provision, with its goal of eventually integration of Kashmir into India proper. The bench also stated that there were no limitations on the president’s power to abrogate the article and that the processes enacted to change the status of Jammu and Kashmir into separate union territories were constitutionally valid. Moreover, the judges affirmed that the Jammu and Kashmir constitution was null and void as it has been replaced by the Indian constitution. The court noted, “Following the application of the Constitution of India in its entirety to the State of Jammu and Kashmir by CO 273, the Constitution of the State of Jammu and Kashmir is inoperative and is declared to have become redundant”.

While the promise of the forthcoming elections provides prospects of hope for some Kashmiris, many continue to oppose the abrogation of Article 370 and the Supreme Court’s ruling.

. . . . .

Dr Imran Ahmed is a Research Fellow at the Institute of South Asian Studies (ISAS), an autonomous research institute in the National University of Singapore (NUS). He can be contacted at iahmed@nus.edu.sg. Mr Muhammad Saad Ul Haque is a research analyst at the same institute. He can be contacted at msaaduh@nus.edu.sg. The authors bear full responsibility for the facts cited and opinions expressed in this paper.

Pic Credit: Wikipedia Commons.

-

More From :

More From :

-

Tags :

Tags :

-

Download PDF

Download PDF