China and India’s FTA with ASEAN:

Divergent Strategies and Outcomes

Sandeep Bhardwaj

10 December 2025Summary

The free trade agreement (FTA) between the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and China is a dynamic, ambitious and successful instrument whereas the ASEAN-India FTA remains mired in suspicions and disappointments. Fundamentally, China’s approach to the FTA is aggressive while India’s approach is defensive.

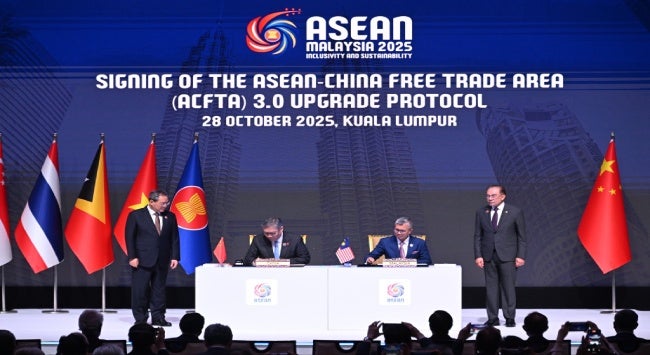

Two revealingly divergent announcements emerged from the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Summit in October this year. The Association upgraded its free trade agreement (FTA) with China for the second time, while the review of its FTA with India remains stuck after 10 rounds of negotiations.

China and India began negotiating FTAs with ASEAN at more or less the same time. Yet, they are in remarkably different positions two decades later. The ASEAN-China Free Trade Area (ACFTA) is a regularly upgraded, expansive and multi-dimensional instrument. In contrast, the ASEAN-India Free Trade Area (AIFTA) has limited scope and ambition, and it is besieged by dissatisfaction and suspicion. Furthermore, it has not been updated in over 10 years.

The weaknesses of the AIFTA highlight the limitations of India’s economic diplomacy, particularly its lack of dynamism, sophistication and capacity for dealmaking. They also undermine India’s political position in the region as they erode the country’s image as an effective and capable actor.

The wave of intra-Asian FTAs began in the aftermath of the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis which shook the region’s faith in the West. ASEAN opened FTA talks with China in 2002 and with India in 2003. Beijing took seven years to negotiate the four elements of the ACFTA: goods trade (2004), dispute settlement (2004), services trade (2007) and investments (2009). New Delhi’s more tortured negotiations took 11 years to complete, as agreements on goods trade (2009), dispute settlement (2009), services trade (2014) and investments (2014) arrived slowly and erratically.

The Indian FTA lacked the ambition of the Chinese FTA. China and ASEAN agreed to eliminate tariffs on around 94 per cent of lines. In comparison, India committed to 78.8 per cent and ASEAN averaged at 79.7 per cent of tariff elimination coverage. In fact, the low ambition of the AIFTA is unusual among all ASEAN+ trade agreements. For instance, Indonesia’s tariff elimination commitment to India was a paltry 48.7 per cent, but it exceeded 90 per cent in ASEAN+ FTAs with China, Japan, Korea, Australia and New Zealand. A pertinent question is why the ASEAN member countries have offered India much less market access than all other major economies in the region.

The ACFTA drastically accelerated the pace of ASEAN-China trade. Based on the author’s calculations, between 2003 and 2021, China’s exports to the ASEAN grew at more than double the rate of its exports to the world. In comparison, India’s exports to ASEAN have grown at about the same rate as its exports to the rest of the world in the last two decades.

China and ASEAN never stopped negotiating to enhance the ACFTA. Between 2003 and 2014, the two sides signed at least seven protocols to amend various elements of the agreement. These included streamlining customs procedures, lowering non-tariff barriers, coordinating sanitary requirements and harmonising technical standards. The momentum was maintained by circumventing contentious issues and aggressively implementing whatever could be agreed on.

In 2015, the ACFTA underwent a major upgrade with a new package of liberalisation commitments. No sooner was the upgrade implemented, the next round of negotiations began, culminating in the ACFTA 3.0 signed in October 2025.

Consistent refurbishing has transformed the ACFTA into an instrument much broader in scope than just tariff reduction. Its latest version expands China-ASEAN cooperation on supply chains, green technology and digital economy, adopting new norms, standards and compliance practices. As a ratified legal treaty, it is a more potent instrument than memorandums of understanding, joint statements, roadmaps or other diplomatic documents that usually address such issues.

India was not only conservative in its ambitions for the AIFTA, but it also developed a buyer’s remorse quickly after the signing. New Delhi’s concerns were exacerbated as its trade deficit with ASEAN, which had existed since the Asian Financial Crisis, ballooned after the agreement came into effect. The ASEAN member countries also expressed their disappointment with the limited scope of the AIFTA.

Nevertheless, no serious negotiations took place to improve the AIFTA. While the two sides agreed in 2015 to review the ASEAN-India Trade in Goods Agreement, the scope of the review endorsed by them suggested that the emphasis was on renegotiating the existing agreement rather upgrading it. The review was delayed due to a variety of reasons. It only began in earnest in 2023 and remains deadlocked until today. Importantly, the review only examines the goods trade component of the FTA. No review of the agreements on services trade and investments is on the cards as of now.

In the recent years, more deadweight has piled on the AIFTA. New Delhi has grown concerned that Southeast Asia is being used as a conduit for Chinese economic penetration into India. Piyush Goyal, India’s commerce minister, ruffled some feathers when he called ASEAN China’s ‘B-Team’ earlier this year.

Remarkably, on paper, Beijing should be in worse position than New Delhi in its negotiations with the ASEAN. Many in Southeast Asia view China with suspicion because of the South China Sea dispute and are discomfited by its economic dominance and enormous trade surplus. The ongoing Sino-United States trade war has further complicated the issue. In comparison, India enjoys political goodwill in the region, and it is not viewed as an economic threat. ASEAN would welcome deeper trading relationship with India for both economic and strategic reasons.

Yet, the AIFTA remains stuck in deadlocks and recriminations while the ACFTA has steadily expanded. India’s approach to FTAs remains defensive while China’s is aggressive. India should take a page from China’s book not only to make its economic diplomacy more robust but if to project itself as a serious, efficacious actor in the region. Robust economic diplomacy will also serve India well as it looks to sign FTAs in other parts of the world.

. . . . .

Dr Sandeep Bhardwaj is a Visiting Research Fellow at the Institute of South Asian Studies (ISAS), an autonomous research institute at the National University of Singapore (NUS). He can be contacted at sbhardwaj@nus.edu.sg. The author bears full responsibility for the facts cited and opinions expressed in this paper.

Pic Credit: X

-

More From :

More From :

-

Tags :

Tags :

-

Download PDF

Download PDF