Summary

The recent Iran-Israel-United States conflict has underlined the intense isolation of Tehran in the world, even from its traditional friends such as India. Over the last two decades, India’s diplomatic and economic stake in Iran has eroded because of the American pressure campaign. The dismantling of India-Iran relationship also reveals deeper shifts in Washington’s approach to India and New Delhi’s shrinking space to manoeuvre.

After the end of the Cold War, New Delhi looked to develop Tehran because it saw Iran serving its interests in three major roles – as a source of reliable and cheap energy; a node in the trade route connecting India to Central Asia and Afghanistan; and a strategic and counter-terror partner on the western flank of Af-Pak.

At a deeper level, developing relations with Iran allowed India to expand its options. Protective of its strategic autonomy, New Delhi was discomfited by the post-1991 American hegemony over the world. It sought to retain greater manoeuvre room for itself by signalling its willingness to work with nations ostracised by the United States (US)-led Western order. India also believed it was helping maintain global stability by acting as a pressure release valve for the countries targeted by Washington.

India’s interest in Iran reached its zenith in the early 2000s, as the Atal Bihari Vajpayee government laid out a far-reaching vision for the bilateral relationship based on a host of infrastructure, commercial and strategic projects. Iran quickly became one of the top suppliers of hydrocarbons to India. New Delhi agreed to develop the port of Chabahar and a rail line connecting it to the Delaram-Zaranj Highway, which India was building in Afghanistan. It developed plans for an overland India-Pakistan-Iran gas (IPI) pipeline. An Indian consortium won a multi-billion-dollar contract to develop the Iranian Farzad-B gas field. The two countries began holding naval exercises. Prime Minister Narendra Modi renewed and expanded India’s commitment to these projects in 2015.

At the same time that Iran-India relations were taking off, the US was also eyeing a strategic partnership with India as a way to balance a rising China. The George Bush administration sought to woo New Delhi by implicitly promising to respect its strategic autonomy and offering it a privileged position within the US-led world order. The centrepiece of Washington’s efforts was a deal that accorded India unique status as a de facto nuclear power.

When Washington’s courting of New Delhi collided with its campaign to isolate Tehran, it chose a strategy of persuasion and accommodation to avoid bruising Indian sensitivities. It used back-room convincing and compensatory sops to wean India away while also acceding to some aspects of India-Iran relations. The Bush administration successfully pulled India out of the IPI pipeline project by offering it greater US-India energy cooperation and applying strong diplomatic pressure. However, Washington, under the Barack Obama and Donald Trump-I administrations, also gave waivers to India from American sanctions to allow Iranian oil and gas imports (at reduced volumes) and continue investments in the Chabahar Port.

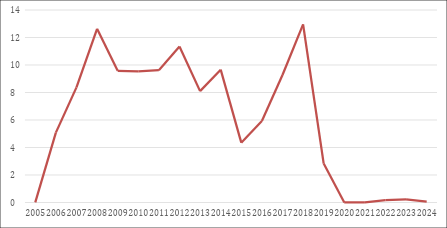

For its part, India tried to walk the tightrope. While chafing at unilateral American sanctions, New Delhi sought exemptions from them rather than try to circumvent them, relying on its ability to leverage its special relationship with Washington. It continued petroleum imports from Iran at advantageous terms, albeit with some reduction (see Figure 1). It also signalled its resistance to American pressure through gestures such as hosting two Iranian navy ships while President Bush visited India in 2006.

The US’ approach shifted in the late 2010s after the Trump administration exited the Iran nuclear deal and launched a maximum pressure campaign to choke the Iranian economy. Whereas before, Washington sought to push New Delhi away from Tehran but allowed it some latitude, now the US moved towards uncompromising coercion. It discontinued the sanction waiver to India for Iranian petroleum imports in 2019. The sanctions regime became much more precise and sweeping; for instance, White House officials started identifying and personally intimidating Indian captains of tankers carrying Iranian oil. The Joe Biden administration continued the aggressive tactics and even threatened to target India’s investment in Chabahar, the one exemption to have survived so far. In 2025, US prosecutors targeted the Adani group, one of India’s largest conglomerates, for allegedly violating Iran sanctions.

Figure 1: India’s Petroleum Imports from Iran (US$ billion)

Source: Data collated by the author from the Ministry of Commerce and Industry, India, and EXIM Bank

The pressure campaign has whittled India-Iran relations to a nub. Unlike China, which decided to resist US sanctions, India’s oil and gas imports from Iran nearly zeroed out after 2019. Most commercial and infrastructure projects envisioned by the Vajpayee government have stalled or died, including the IPI Pipeline, the Farzad-B gas field project and the Chabahar-Zahedan railway link. Chabahar port, the only major project to survive, has also failed to take off due to sanctions – only 450 vessels have visited it in the last six years. Although the economic and strategic rationales for closer India-Iran ties still exist on paper, the two nations have drifted apart in the absence of any concrete link holding them together.

New Delhi’s inability to navigate Washington’s maximum pressure campaign to preserve some degree of its relationship with Tehran hints at the shrinking room for India to manoeuvre geopolitically. This is partly due to the increasing polarisation of international politics in the last few years. It is also because the US has become less inclined to cater to Indian sensitivities or accord it special concessions. It has grown impatient with India’s hesitation to join its anti-China alliance. Many in Washington are questioning the policy, established by the Bush administration, to court New Delhi even if it insists on charting an independent path. This shift in the US’ approach is likely to trigger a reckoning in India, whether and how to preserve its strategic autonomy.

. . . . .

Dr Sandeep Bhardwaj is a Visiting Research Fellow at the Institute of South Asian Studies (ISAS), an autonomous research institute at the National University of Singapore (NUS). He can be contacted at sbhardwaj@nus.edu.sg. The author bears full responsibility for the facts cited and opinions expressed in this paper.

Pic Credit: Wikimedia commons

-

More From :

More From :

-

Tags :

Tags :

-

Download PDF

Download PDF