Summary

On 1 February 2025, India presented what Prime Minister Narendra Modi described as the ‘most middle-class friendly budget in India’s history’. It will be interesting to see if the support for the middle class revives consumption and supports gross domestic product growth.

The significance of the middle class as a constituency is often ignored. This was not the case in India’s latest Union Budget, which was presented on 1 February 2025. The Union budget for the financial year (FY) 2025-2026 is one that has aimed to deliver where the middle class would have wanted it the most: lowering income taxes.

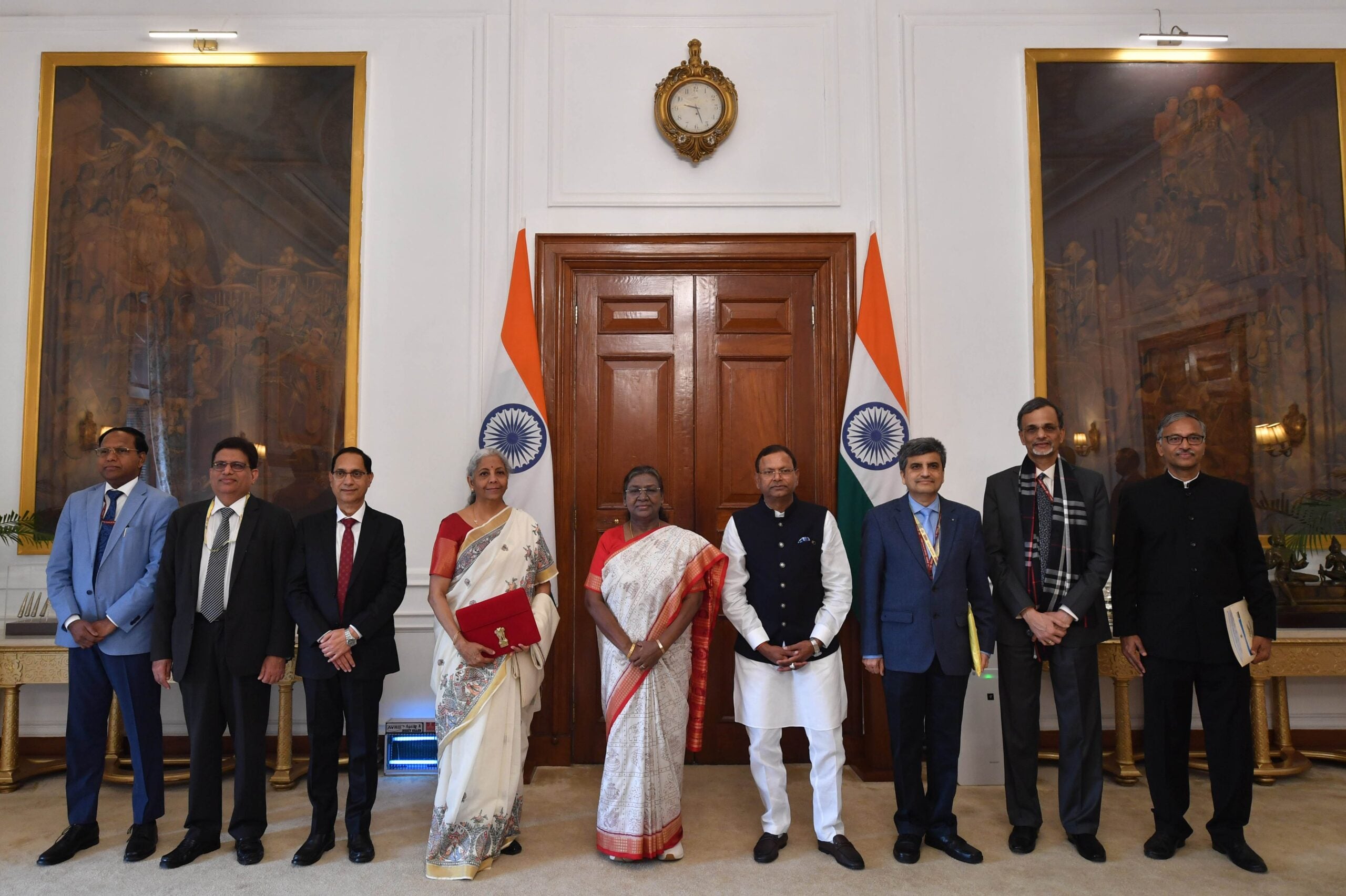

Presenting the tax proposals, Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman mentioned that incomes up to ₹1.2 million (S$18,800) will no longer be paying income tax. This reflects an increase of ₹500,000 (S$7,838) or around a 70 per cent rise from the earlier level of threshold tax-free income of ₹700,000 (S$10,972).

The ‘power’ of the middle class in swinging economic policy in its favour has hardly ever been as conspicuous as in this budget. Right at the beginning of her speech, the finance minister mentioned ‘enhance spending power of India’s rising middle class’ as one of the five key areas of effort for the government in the budget. Subsequently, she returned to the middle class again while introducing her direct tax proposals, suggesting that one of the objectives of the proposals was reform of personal income tax with a special focus on the middle class. The new revised tax slabs and lower rates, she stated, ‘will substantially reduce the taxes of the middle class and leave more money in their hands, boosting household consumption, savings and investment’.

It is also noteworthy that Prime Minister Narendra Modi described the Union budget as ‘the most middle class friendly budget in India’s history’, underlining both the economic and popular implications of the budget.

There are strong reasons for the budget’s focus on improving the prosperity of the middle class.

After cruising at an annual rate of growth of eight per cent plus in gross domestic product (GDP) in its immediate rebound years after the COVID-19 pandemic, the Indian economy is showing signs of slowing down. The GDP growth for FY2025, according to the latest Economic Survey of the Ministry of Finance in India, is projected at 6.4 per cent. The survey also forecasts the GDP growth for FY2026 to be between 6.3 per cent and 6.8 per cent. The reduction in GDP growth will also imply a decline in consumption demand and expenditure, thereby further impacting GDP growth. In order to address the problem, it is essential for consumer demand to be sustained. One of the surest ways of doing so is to put more money in the hands of people and households. The lowering of personal income tax aims to achieve this objective.

The number of taxpayers in India is less than seven per cent of its population. The taxpayers largely comprise the salaried middle class urban population of the country. This section of the population is not a beneficiary of the various income support schemes that the central and state governments have been offering over the years, particularly after the COVID-19 pandemic. They are not beneficiaries of employment assistance or subsidised food grains. The overwhelming focus of public policy over the last few years has been on expanding the welfare schemes for the poor and marginal sections of the population. While that has had its virtuous effects, the middle class has progressively felt squeezed on earnings and savings. With retrenchment and job losses rising, salary incomes stagnating and expenditures going through the roof, the middle class has been at the receiving end of India’s economic transition. Indeed, the steady increase in India’s household debt, as a proportion of GDP, now at 38 per cent, demonstrates the rising tendency of the urban middle households to resort to borrowings for both consumption and investments, including in purchases of housing and retail. Higher borrowings and rising costs of housing, healthcare, education and daily essentials have been hitting the middle class hard, more so after the COVID-19 outbreak.

It was, therefore, essential for the government to show its commitment to the middle class, which it has, by cutting income taxes. In all respects, the move is a ‘win-win’ step. By putting more money in the hands of those who now face a higher threshold of tax-free income, there is a good chance of reviving personal consumption. This should ensure that sectors and industries that have been thriving on the support of the middle class – retail, hospitality, tourism, entertainment, healthcare, education and transport – continue to receive the support. Higher consumption is great news for businesses and industries as they register higher sales and revenues. There could be nothing better for the government too, as more sales and revenues ensure higher overall revenue collections through Goods and Services Tax and various other state levies.

The ‘middle-class’ focus of the budget will be an interesting example of how much driving ability the class has in stabilising India’s economic fortunes. FY2026 will provide the answer.

. . . . .

Dr Amitendu Palit is a Senior Research Fellow and Research Lead (Trade and Economics) at the Institute of South Asian Studies (ISAS), an autonomous research institute at the National University of Singapore (NUS). He can be contacted at isasap@nus.edu.sg. The author bears full responsibility for the facts cited and opinions expressed in this paper.

Pic Credit: X

-

More From :

More From :

-

Tags :

Tags :

-

Download PDF

Download PDF