Summary

In a new and productive framing of India’s current relationship with the West, External Affairs Minister Subrahmanyam Jaishankar has broken out of India’s prolonged post-colonial corner that it had boxed itself into. By affirming that India is not “anti-West” but “non-West”, Jaishankar has expanded the domestic room for manoeuvre on great powers relations. The new framing allows Delhi to seek deeper ties with the United States and Europe without being branded as pro-West at home.

Participating in a panel discussion at the annual Munich Security Conference on 17 February 2024, along with United States (US) Secretary of State Antony Blinken and German Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock, India’s External Affairs Minister Subrahmanyam Jaishankar offered a new template to think through New Delhi’s great power relations.

Jaishankar was responding to a question about India’s apparent freedom to choose between multiple partners, including the US, Europe and Russia, and the implicit assumption that the Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa (BRICS) forum, dominated by Beijing and Moscow, was “anti-Western”. Affirming the distinction “between being non-West and anti-West”, Jaishankar said he would “characterise India as a country, which is non-West, but which has an extremely strong relation with the Western countries, getting better by the days”. He added that that definition might not apply to the other members of BRICS.

While Russia and China might want to turn BRICS into an anti-Western forum, Jaishankar said India had no interest in such an agenda. At the same time, he insisted that Delhi sees value in BRICS as a “non-Western” forum with demonstrated potential in democratising global governance.

Although many in the West are dismayed by Delhi’s close ties to Russia and BRICS, Blinken did not quarrel with Jaishankar’s formulation. He endorsed Jaishankar’s case for “flexibility” in international relations and underlined the importance of “variable geometry” in the current global context. Rejecting the division of the world into “rigid blocks”, Blinken said the US “may have different collections and coalitions of countries that bring certain experiences and capacities” in dealing with different challenges. He added that the “relationship between our countries is the strongest it’s ever been”, and it “makes no difference that India happens to be a leading member of BRICS”, and he pointed to wide-ranging international collaboration between Delhi and Washington, including in the Quadrilateral Security Forum, along with Australia and Japan.

This new comfort level at the highest political level in Delhi and Washington with the apparent geopolitical contradictions does not always filter down to Delhi’s foreign policy discourse that has long defined India’s international relations in anti-Western terms. The anti-imperial left and the nativist right in India, as well as the centrist Congress party and the national security establishment, have long operated on the assumption that the contradictions between India and the US are difficult to resolve.

The Narendra Modi government has transcended this paradigm by shedding the ‘historical hesitations’ in engaging the US. This has helped move India and the US closer than ever before. The decline of the left in India and the weakening of the Congress removed much of the traditional resistance to India’s productive engagement with the West. However, there is residual resistance among India’s rising conservative nationalist forces. In framing India as “non-West” but not “anti-West”, the Modi government consolidates the support of the Hindu right for its foreign policy while leaving much room open for closer ties with the US and Europe.

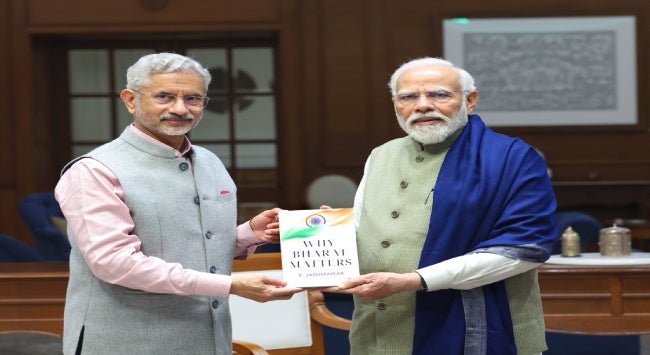

In his new book, Why Bharat Matters, Jaishankar offers a more detailed delineation of the proposition that India is “non-West but not anti-West”. Discussing India’s much-touted ‘strategic autonomy’, Jaishankar writes that the concept is usually interpreted as “keeping distance from the West, especially the US”. “The irony is that this has led us instead to develop deep dependencies elsewhere.” (Why Bharat Matters, page 98) The reference is to India’s dependence on Russia for arms imports and China for manufactured goods.

Central to Jaishankar’s argument is the recognition that ‘strategic autonomy’ and ‘non-alignment’ had become ideological blinkers that prevented India from taking full advantage of the possibilities with the West in the past. Jaishankar reminds his Indian audience that most East Asian nations have progressed in partnership with the West, especially the US. He avers that India must learn from the East Asian experience to leverage “geopolitics for national development”. He points to the current polarisation in Asia and the emerging fit between the economic, technological and political interests of India and the West. (Why Bharat Matters, page 98)

At the same time, Jaishankar recognises the challenges of navigating the growing tensions between Russia and the West. He appeals to the Western partners to understand the historical evolution of India’s relationship with Russia and its continuing relevance for Asian security. Delhi does not believe, Jaishankar suggests, that Moscow will inevitably become a junior partner for Beijing; a productive engagement with Russia remains key to India’s quest for a stable Asian balance of power from his perspective. (Why Bharat Matters, pages 99-100)

As he celebrates the progress in the ties with the US and Europe over the last decade, Jaishankar is acutely conscious of the continuing challenges in engaging the West. He points to the liberal hegemonism in the West that tends to meddle in the affairs of other countries and the tensions that it inevitably generates with “post-colonial polities like India, which are reasserting their identities and standing their ground”. (Why Bharat Matters, page 97)

Jaishankar’s often blunt reaffirmation of India’s interests and identity when it comes to the difficulties with the West has resonated well with the nationalist constituencies of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). At the same time, an openness to deeper engagement with the West has ensured that New Delhi’s American and European partners have a rising stake in good relations with the Modi government. Jaishankar’s “non-West, but not anti-West” is integral to India’s current nimble foreign policy strategy. It is also part of an effort to reconcile the new assertive Indian nationalism of the BJP with the deepening strategic ties with the US and the West.

. . . . .

Professor C Raja Mohan is a Visiting Research Professor at the Institute of South Asian Studies (ISAS), an autonomous research institute at the National University of Singapore (NUS). He can be contacted at crmohan@nus.edu.sg. The author bears full responsibility for the facts cited and opinions expressed in this paper.

Pic Credit: S Jaishankar Twitter Account

-

More From :

More From :

-

Tags :

Tags :

-

Download PDF

Download PDF