Human Rights, Geopolitics and National Priorities: Managing Fluctuations in US-Sri Lanka Relations

Roshni Kapur, Chulanee Attanayake

2 June 2021Summary

Economic and political relations between Colombo and Washington have fluctuated throughout their history. The variations in their bilateral relations are parallel to the regime changes in Colombo. This paper explores the themes of trade and economic cooperation, human rights, and geopolitics and military engagement in their relations, and how they have evolved over the years under different leaders in both countries. It also explores the possible trajectory of their relations under the current Sri Lankan government led by Gotabaya Rajapaksa and the American government under the Joe Biden administration.

Introduction

Sri Lanka was established in 1948. One of the first countries to recognise its independence, the United States (US) is amongst Sri Lanka’s oldest diplomatic partners. Both are part of many global institutions and engage actively in the multilateral system.

An interesting dynamic is how bilateral relations vary with the ruling political party in Colombo. Sri Lanka, a multi-party democracy, has been dominated by two formidable parties – the United National Party (UNP) and the Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP) – whose foreign policy orientations are notably different. While the UNP’s foreign policy is West-leaning, the SLFP is skewed more towards the eastern bloc1. As a result, Sri Lankan-American bilateral relations have historically been stronger whenever the UNP-led government has been in power.

Trade and Economic Cooperation

The US was among Sri Lanka’s main trading partners even at the time of its independence. It was among the main export destinations, along with the United Kingdom and India2. However, between the 1960s and early 1970s, bilateral trade relations suffered a setback due to Colombo’s protectionist economic policies and de-privatisation of industries3. It was the macroeconomic reforms in 1977 followed by expansion of the export structure, including the establishment of Export Processing Zones in 1978, which enabled Colombo to adopt an outward-centric trade regime that improved its relations with the US. The US gradually emerged as a major trading partner4. Since 1979, the US has remained the single largest buyer of Sri Lankan exports, which has generally experienced an upward trajectory.

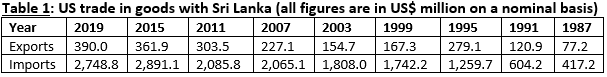

The notable declines in the trade corporation were in the early 2000s and during the global financial crisis in 2007-08. In 2001, external trade in Colombo became costly due to, among other reasons, the higher premium imposed on freight insurance and the risks brought by the civil war. The country’s exports were also impacted by the subprime mortgage crisis in the US in 2007-085. These setbacks were reversed when the global economy recovered in 2010. The US offering the Generalized System of Preferences to Sri Lankan exports since 19706 and the signing of the Trade and Investment Framework Agreement (TIFA) have contributed to this growth. The TIFA, signed in 20027, the Joint Action Plan established in 2016 to increase bilateral trade and the continuous TIFA discussions, including the latest in June 20198, have contributed to the positive growth in trade as shown in Table 1.

Source: Trade in Goods with Sri Lanka, US Census, https://www.census.gov/foreign-trade/balance/c5420.html.

While the US primarily imports apparel, rubber, tea, spices and industrial supplies, its exports to Colombo include medical equipment, plastics, cloth, textiles, dairy products and animal feeds9. Even though Sri Lankan exports are less competitive than some of its Asian counterparts, including Vietnam and Bangladesh, the depreciation of the Sri Lankan rupee and increase in the minimum wage for workers in Bangladesh’s garment sector have given Colombo an advantage.

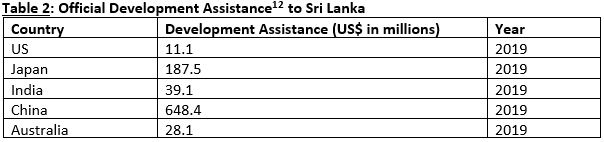

While the US’ foreign direct investment (FDI) stock in Sri Lanka was around US$165 million (S$218.44 million) in Sri Lankan FDI stock in the US was around US$67 million (S$88.7 million) in 201910. American development assistance has only been around US$2 billion (S$2.67 billion) to Colombo since 1948. That Washington has a reputation for being the world’s bigger provider of bilateral assistance in health, it provided Colombo with more than US$5 million (S$6.66 million) in assistance and donated 200 ventilators to support the latter in its fight against COVID-1911.

Source: Annual Performance Report 201, Department of External Resource Sri Lanka, https://www.dfat.gov.au/geo/sri-lanka/development-assistance/development-assistance-in-sri-lanka.

Human Rights and Democratic Institutions

Despite longstanding trade and economic ties, relations between Sri Lanka and the US are based on shared democratic traditions, issues of human rights, democracy and rule of law and that has taken precedence13. The US’ policy of engagement with Colombo is focused on, among others, supporting efforts to reform the island nation’s democratic political system to facilitate full political participation of all communities, promoting political reconciliation and community integration14.

As such, bilateral relations deteriorated during the final stages of the Sri Lankan civil war due to allegations of human rights violations and perceived authoritarianism under the SLFP led by Mahinda Rajapaksa15. The two countries had divergent approaches to ending the highly intractable war between the Sri Lankan state and the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE)16. While Washington insisted on reviving the peace process with the LTTE, the Rajapaksa government had directed its efforts towards militarily defeating the terrorist group, given that the latter had suspended peace talks retrospectively17.

US President Barack Obama’s government, which was in power at the time, had also pressurised Sri Lanka in addressing issues of accountability, reconciliation and institutional reform following the end of the civil war18. A report commissioned by the United Nations (UN) stated that around 20,000 civilians may have been killed during the final phase of the war19. The Rajapaksa government, however, refuted these claims asserting that the military operations were aimed at saving Tamil civilians who were trapped in the conflict zone, and refusedforeign involvement in the country’s homegrown reconciliation process, including the Lessons Learnt and Reconciliation Commission, Commission of Inquiry on Disappearances and an Army Court of Inquiry. Rajapaksa’s administration saw an international inquiry as a violation of state sovereignty and incompatible with the constitution. It contended that there was a trend by the West to interfere in the internal matters of countries in the Global South under the disguise of security and human rights20. Another reason for opposing international involvement in the accountability and reconciliation processes could be the lack of local expertise and understanding of ground realities by international experts. The clashing approaches on issues of military strategy, accountability and human rights led to a deterioration of relations between the two sides.

Geopolitics and Military Engagement

Historically, the US has had limited military relations with Colombo. Apart from the training provided under the International Military Exchange and Training programme and Pacific Command’s Extended Relations Programme, there were few joint military exercises and no arms trading21.

For a significant period, military cooperation between Washington and Colombo was driven by the worsening of the separatist war. In 1996, the US approved Israel’s decision to sell six Kafir jets and three fast patrol boats to the Sri Lankan navy. It also started Operation Balanced Style, a military operation to train Sri Lankan soldiers against their fight on terrorism and offered training to Sri Lankan officers at the US Military Academy West Point. The US Green Berets and Navy SEALS also trained the Sri Lankan army in tactical reconnaissance, long-range patrolling, maritime operations, and air and sea attacks to stop the LTTE from gaining access to supply bases in Tamil Nadu22. Military relations improved significantly after Ranil Wickremesinghe became Sri Lanka’s prime minister in 200223. There were greater high-level delegation visits by US military officials and port calls to Colombo. One of the prominent visits was by then Assistant Secretary for South Asian Affairs, Christina Rocca, who affirmed Washington’s commitment to supporting Colombo in the peace process and joined Wickremesinghe during his historic visit to the northern part of the country24. While Wickremesinghe’s accession to power contributed to the strengthening diplomatic relations between the two countries, it should not be considered as the only factor. When the US donated a Coast Guard 210-foot cutter to the Sri Lankan navy in 200425, Rajapaksa was the incumbent prime minister at that period. The US’ war on terror following the September 9/11 attacks could have been a motivating factor in its foreign policy shift towards Sri Lanka. This could explain why Washington decided to provide intelligence support to Colombo in its fight against terrorism. For instance, the US warned Colombo that floating arsenals were present on the high seas in 2007 that gave the Sri Lankan navy an advantage in destroying the LTTE arms supply ships26. However, the US was also of the view that Sri Lanka should negotiate/re-negotiate with the LTTE and it should not try to resolve the conflict through military means. The US took different measures to pressurise Sri Lanka. For instance, then US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton threatened to block a crucial International Monetary Fund loan to Sri Lanka over the intensifying conflict. The US’ continuous pressure during and after the war which ended in May 2009, followed by isolation from partners such as Japan and the West were among the main reasons for the Rajapaksa government’s tilt towards China. China’s diplomatic and military support throughout the military operation and afterwards made Beijing increase its footprints in Sri Lanka.

Post-2015 Bilateral Relations

The unexpected victory of the breakaway faction led by Maithripala Sirisena in 2015 was a significant turning point in Sri Lanka’s domestic politics as well as its international relations. Many international observers viewed the victory as paving the way for the country’s path to a democratic renaissance27 that resulted in considerable achievements, including ending the intimidation of journalists, unblocking websites that were critical of the government, removing surveillance of critics and creating a democratic space to discuss sensitive issues28.

The Sirisena-Wickremesinghe administration gave the US an opportunity to restore its relationship with Colombo mostly for geopolitical factors, and led initiatives to strengthen economic and political relations29. The US actively promoted the Sirisena-led government through high-level visits, press releases and media statements. For instance, Nisha Biswal, then Assistant Secretary of State for South and Central Asia, visited Colombo six times over 20 months. Then US Secretary of State John Kerry also visited Colombo, marking the first visit by a US Secretary of State to the country in a decade30. Thomas Shannon, former state department counsellor, praised the government for its “contributions to the development of a regional consciousness – one that promotes the values of democratic governance and respect for human rights, freedom of navigation, sustainable development, and environmental stewardship are noteworthy31” and announced the US-Sri Lanka Partnership Dialogue during his visit in December 2015.

The reconfiguration in foreign policy under the Sirisena government played a role in improving bilateral relations. The US also supported Colombo’s new reconciliation and accountability agenda with greater resources and programming32, while Colombo agreed to co-sponsor the 30/1 resolution to set up a new transitional justice model comprising a Truth and Reconciliation Commission, Office of Missing Persons, Reparations Office, and a special court to prosecute the alleged perpetrators within an 18-month deadline. However, the coalition government struggled to implement its ambitious reform agenda of tackling corruption, economic reforms and transitional justice, and the early enthusiasm and commitment for meaningful change waned away33. For instance, the process of gazetting the laws, operationalising the offices, releasing the reports and implementing the recommendations were delayed. The government also retracted some of its promises, including establishing a hybrid court with the involvement of foreign judges. Even so, the UN Human Rights Commission’s (UNHRC) postponed the release of a report on crimes committed during the civil war indicating the international community, led by the US, still harboured hopes that the Sirisena government would fulfil its promises34.

The US’ active promotion of Colombo under the Sirisena administration was similar to its embrace of the regime change in Myanmar when Aung San Suu Kyi’s party won in the 2015 general elections35 leading to speculations that it was reliving the ‘Myanmar moment’ in Sri Lanka.

Even when the administrations changed in the US when Donald Trump assumed power, bilateral relations continued to grow. Colombo welcomed several high-level military officials and hosted port calls from the US, including the participation of Admiral Harry B Harris, then Commander of the US Pacific Command, at the 2016 Galle Dialogue36. Since then, the US has sent its representatives to attend the Galle Dialogue to highlight the stronger maritime relations between the two sides. In 2016, the US Air Force’s Operation Pacific Angle carried out a humanitarian mission with its Sri Lankan counterpart in the north of Sri Lanka. In the same year, the US maritime patrol aircraft, Red Lancers of Patrol Squadron Ten (VP-10), visited Colombo for a week during its regular visit to the Indo-Pacific region37. In 2018, Colombo was invited to participate in the world’s biggest maritime exercise, the Rim of the Pacific Exercise. These joint exercises between Washington and Colombo could be perceived as the latter’s attempt to reorient its foreign policy towards a more neutral path.

The cooperation between the two countries in maritime security is an outcome of their vested interests in strengthening their maritime relations in the Indian Ocean. The Indian Ocean region was historically an inclusive part of Sri Lanka’s strategic, political, and security narratives. Despite being a small state, it initiated new legislation on upholding a rules-based maritime order in the Indian Ocean38. However, its consciousness declined due to domestic issues, including the highly protracted civil war39. Of late, a new body of historical and sociological literature is replacing the Sri Lankan identity within a bigger Indian Ocean narrative. Successive governments have made policy decisions for the ocean to take centre stage for greater economic development such as turning Colombo into an air and naval hub40. Colombo’s strategic location in the Indian Ocean and close to the sea lines of communication has become increasingly significant over the years.

In parallel, the US’ vision for the Indo-Pacific under both the Obama and Trump administrations was partly driven by China’s increasing footprint in the region. The US has increased its security ambitions in the Indian Ocean region and its littorals. Washington perceives small states such as Colombo as sandwiched between its Indo-Pacific policy and China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). China’s efforts to build infrastructure in the South Asian countries, including Sri Lanka, have been perceived by the US and its allies as a “string of pearls” naval strategy41. This has prompted the US to engage with Colombo in recent years. In response, Sri Lanka has maintained its hedging strategy by accepting both the Indo-Pacific strategy and the BRI projects.

Another reason for the improved relations between the two countries could be the Trump administration’s indifference towards issues of human rights and accountability which has always been an obstacle in the earlier years. The US’ relationship with the UNHRC was factitious over perceptions that the latter had turned increasingly politicised and selective in its scrutiny of human rights issues. In 2018, Washington exited from the UNHRC and claimed that it would work outside the Council to promote and protect issues of human rights42. As a result, human rights did not become an obstacle for Washington and Colombo to explore possibilities for cooperation even when the Gotabaya administration came into power towards the latter half of the Trump administration. Hence, the Gotabaya government’s withdrawal from the 30/1 co-sponsored resolution in 2020 did not create friction with the US. Moreover, Washington’s engagement with Colombo on human rights issues under Trump was largely personal and independent such as in the case of a travel ban on Sri Lankan army chief Shavendra Silva and his immediate family in 2020 over allegations that he orchestrated war crimes during the civil war43. However, the travel ban did not bode well with Colombo given that Silva is deemed as a war hero in the Sri Lankan society.

Prospective Relations under Rajapaksa-Biden Administrations

Following the presidential elections in Sri Lanka and the US in 2019 and 2020 respectively, the equation between Colombo and Washington has turned to what it was a decade ago. The US is governed by a Democrat administration at a time when Sri Lanka’s president is a Rajapaksa. Historically, the Rajapaksas and the Democrats have not shared a harmonious relationship. In this context, there are questions on whether the dynamics will be similar under the new leaderships. The US’ Democrat government during the Obama administration perceived the Rajapaksa government to be populist, anti-democratic and authoritarian. Moreover, the Rajapaksas’ close ties with China are contrary to the US interests in Sri Lanka. Similarly, the Rajapaksas consider the US under the Democrats as pursuing an interventionist and intrusive foreign policy which they do not welcome. Allegations of human rights violations continue to remain unaddressed. Gotabaya has reiterated Colombo’s non-aligned and neutral foreign policy that it has upheld for decades. It has used this policy to emphasise the moral high ground of non-interference in the country’s foreign policy44. Hence, the future bilateral relations between the US and Sri Lanka will depend on how both countries accommodate each other’s different interests.

While the Millennium Challenge Compact (MCC) and Status of Forces Agreement were on the agenda during the Sri Lankan presidential elections in 2019, and even though both Gotabaya and his main rival Sajith Premadasa pledged to scrap the deals, it was felt that Gotabaya may take a pragmatic approach. However, his administration cancelled the MCC following a report submitted by a four-member expert committee he appointed to assess the viability of the deal. In its final report submitted to the president in June 2020, the committee held the view that it would not be advisable to sign the contract without changing some of the clauses45. The MCC has turned into a political issue in Colombo. Many nationalist and civil society groups in Sri Lanka perceive the MCC as a ‘neo-imperialist’ project that pushes for economic hegemony over developing countries. Hence, Gotabaya may have faced a backlash by signing the MCC from its cohort of his supporters who were against the deal. As a result, Gotabaya’s administration has begun its relations with the US on the wrong footing.

Issues of human rights are likely to dominate the foreign policy discourse between the two countries soon. Unlike Trump, who pursued an ‘America First’ foreign policy, Biden is expected to pursue a more traditional approach to foreign policy by supporting and rejoining multilateral institutions and restoring relations with allies. While Trump pursued an independent, unilateralist and personal approach to Washington’s relations with Colombo, Biden might engage the latter through multilateral institutions. His administration has already stated its interest to re-join the UNHRC although it is unclear how long such a process would take. Even though Washington is no longer a member of the Council, its influence on the UNHRC should not be underestimated.

The US supported its allies during the recently concluded resolution against Sri Lanka. The Biden administration would assert its leverage on the Council to critically engage on pressing human rights issues in Colombo. Biden is also expected to raise issues of federalism, post-war reconciliation, and the Tamil situation with Colombo and might pressurise the latter to rejoin the UNHRC resolution on reconciliation and accountability. However, American pressure on Colombo to implement a range of reforms could be deemed as another endeavour to undermine state sovereignty and a blot on Sri Lanka’s state institutions.

Against this backdrop, it is unclear how Sri Lanka will move forward in such areas as maritime partnership which has seen improvements in their bilateral relations. The US’ orientation and focus on the Indo-Pacific and its regional allies are likely to continue under Biden’s leadership as he will attempt to end the country’s isolationist position that came into being under the Trump era. This is an opportunity for Sri Lanka to advance its maritime presence and interests in the Indo-Pacific. Therefore, Sri Lanka should not let the conflicting aspects of the relationship undermine the opportunities. Moreover, the US is among Sri Lanka’s main export destinations for its garments industry. American financial institutions are also big investors in Sri Lankan bonds46. Thus, the focus should be on improving and expanding trade and economic ties.

Conclusion

It is not an exaggeration that Sri Lanka’s ties with the US fluctuate according to the party in power in Washington and Colombo. The relations could deteriorate under the Biden era if human rights and post-war reconciliation dominates the discourse. The equation between the two countries could return to what it was a decade ago. As Colombo advances its maritime presence and interests in the Indo-Pacific, and reclaim its Indian Ocean identity, Washington will seek to secure its maritime interests in the region. The Biden and Gotabaya administrations would, therefore, need to strike a balance between short-term strategic gains and a long-term vision for the countries’ bilateral relations.

. . . . .

Ms Roshni Kapur is a former Research Analyst at the Institute of South Asian Studies (ISAS), an autonomous research institute at the National University of Singapore (NUS). She can be contacted at kapur.roshni@gmail.com. Dr Chulanee Attanayake is a Visiting Research Fellow at ISAS. She can be contacted at chulanee@nus.edu.sg. The authors bear full responsibility for the facts cited and opinions expressed in this paper.

Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons.

1 Chulanee Attanayake, “The RIMPAC Exercise and Evolving United States-Sri Lanka Military Relations”, ISAS Working Paper, No. 305, 13 August 2018, pp. 4-5, https://www.isas.nus.edu.sg/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/ISAS-Working-Paper-No.-305.pdf.

2 M K Jayawardena, Mrs MK. “Sri Lanka’s External Trade Relations”, 60th Anniversary Commemorative Volume of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka, 1950-2010 (2011), p. 133.

3 For more information, see Saman Kelegama, “Development in independent Sri Lanka: What went wrong?”, Economic and Political Weekly (2000): 1477-1490; and M K Jayawardena, “Sri Lanka’s External Trade Relations”, op. cit.

4 Jayawardena, “Sri Lanka’s External Trade Relations”, op. cit., pp. 135-137.

5 Ibid, p. 138.

6 “Sri Lanka-Trade Agreements”, export.gov, 22 July 2019, https://www.export.gov/apex/article2?id=Sri-Lanka-Trade-Agreements. Accessed on 30 April 2021.

7 “Trade & Investment Framework Agreements”, Office of the United States Trade Representative, https://ustr.gov/trade-agreements/trade-investment-framework-agreements. Accessed on 22 April 2021.

8 “Sri Lanka-Trade Agreements”, export.gov, op. cit.

9 “U.S. Relations with Sri Lanka”, U.S. Department of State, 27 July 2020, https://www.state.gov/u-s-relations-with-sri-lanka/#:~:text=U.S.%2DSri%20Lanka%20relations%20are,and%20prosperous%20Indo%2DPacific%20region. Accessed on 4 May 2021.

10 “Sri Lanka, Office of the United States Trade Representative, https://ustr.gov/countries-regions/south-central-asia/sri-lanka, Accessed on 2 May 2021.

11 “U.S. Relations with Sri Lanka”, op. cit.

12 It includes both loans and grants offered.

13 Committee on Foreign Relations United States Senate, “Sri Lanka: Recharting U.S. Strategy After the War”, One Hundred Eleventh Congress First Session, (December 2009).

14 Ibid; and U.S. Department of State, Congressional Budget Justification for Foreign Operations, FY2012, Annex: Regional Perspectives.

15 “US must not ignore Sri Lanka’s human rights violations”, The Hill, 17 April 2017, https://thehill.com/blogs/pundits-blog/international/329112-us-must-not-ignore-sri-lankas-human-rights-violations. Accessed on 16 April 2021.

16 It should be noted that the US designated the LTTE as a Foreign Terrorist Organization in 1997.

17 Chulanee Attanayake, “The RIMPAC Exercise and Evolving United States-Sri Lanka Military Relations”, op. cit.

18 Taylor Dibbert, “The future of US-Sri Lanka relations”, The Diplomat, 8 December 2015, https://thediplomat.com/2015/12/the-future-of-us-sri-lanka-relations/. Accessed on 22 April 2021.

19 United Nations, “Civilian casualties in Sri Lanka conflict ‘unacceptably high’ – Ban”, 1 June 2009, https://news.un.org/en/story/2009/06/301852. Accessed on 18 April 2021.

20 Cronin-Furman, Kate, “Human Rights Half Measures: Avoiding Accountability in Postwar Si Lanka”, World Politics 72, no.1 (January 2020), pp. 142-146.

21 Chulanee Attanayake, “The RIMPAC Exercise and Evolving United States-Sri Lanka Military Relations”, op. cit.

22 “U.S. military trains foreign troops”, The Washington Post, https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/national/longterm/overseas/overseas1b.htm. Accessed on 24 April 2021.

23 Ranil Wickremesinghe is known for having a pro-Western foreign policy orientation.

24 “Sri Lankan PM makes first visit to war-ravaged north in 22 years”, Reliefweb, 14 March 2002, https://m.reliefweb.int/report/97384/sri-lanka/sri-lankan-pm-makes-first-visit-war-ravaged-north-22-years?lang=ru. Accessed on 22 April 2021. Wickremesinghe’s visit to the North (Jaffna peninsula) was the first by a Sri Lankan prime minister in 22 years.

25 “Admiral Sandagiri accepts transfer of former US coast guard vessel “Courageous”, Embassy of Sri Lanka, 24 June 2004, http://www.slembassyusa.org/press_releases/summer_2004/admiral_Sadagiri_accepts_24jun04.html. Accessed on 22 April 2021.

26 Chulanee Attanayake, “The RIMPAC Exercise and Evolving United States-Sri Lanka Military Relations”, op. cit.

27 “Sri Lanka between elections”, International Crisis Group, 12 August 2015, p. i.

28 Ibid, p. 2.

29 “Foreign Assistance in Sri Lanka”, foreignassistance.gov, https://foreignassistance.gov/explore/country/Sri-Lanka. Accessed on 20 April 2021.

30 Chulanee Attanayake, “The RIMPAC Exercise and Evolving United States-Sri Lanka Military Relations”, op. cit.

31 Taylor Dibbert, “Renewed US-Sri Lanka Relations: A Sobering Love Affair”, The Diplomat, 17 December 2015, https://thediplomat.com/2015/12/renewed-us-sri-lanka-relations-a-slobbering-love-affair/. Accessed on 24 April 2021.

32 “Foreign Assistance in Sri Lanka”, foreignassistance.gov, op. cit.

33 Taylor Dibbert, “For Sri Lanka, U.S. Security Cooperation is not the cure”, War on the Rocks, 3 April 2017, https://warontherocks.com/2017/04/for-sri-lanka-u-s-security-cooperation-is-not-the-cure/. Accessed on 22 April 2021.

34 Taylor Dibbert, “Sri Lanka: Can Sirisena deliver on reforms?” The Diplomat, 14 April 2015, https://thediplomat.com/2015/04/sri-lanka-can-sirisena-deliver-on-reforms/. Accessed on 22 April 2021.

35 Taylor Dibbert, “The future of US-Sri Lanka relations”, The Diplomat, 8 December 2015, https://thediplomat.com/2015/12/the-future-of-us-sri-lanka-relations. Accessed on 22 April 2021.

36 “U.S. welcomes Sri Lanka’s contribution to security in the Indo-Asia-Pacific region”, U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, 29 November 2016, https://www.pacom.mil/Media/News/News-Article-View/Article/1015066/us-welcomes-sri-lankas-contribution-to-security-in-the-indo-asia-pacific-region/. Accessed on 24 April 2021.

37 Chulanee Attanayake, “The RIMPAC Exercise and Evolving United States-Sri Lanka Military Relations”, op. cit.

38 Asanga Abeyagoonasekera, “America and China Dock in Sri Lanka”, President Biden and South Asia, South Asia Discussion Papers, Institute of South Asian Studies, pp 51-59, https://www.isas.nus.edu.sg/papers/president-biden-and-south-asia/.

39 Chulanee Attanayake, Roshni Kapur, “Sri Lanka and Japan: Emerging Partnership”, ISAS Working Paper, No. 316, 26 February 2019, p. 7, https://www.isas.nus.edu.sg/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/ISAS-Working-Papers-No.-316-Sri-Lanka-and-Japan-Emerging-Partnership.pdf .

40 Ibid.

41 Bruce Vaughn, “Sri Lanka: Background and U.S. Relations”, CRS Report for Congress, 16 June 2011, pp. 5- 6.

42 Colin Dwyer, “U.S. announces its withdrawal from U.N. Human Rights Council”, NPR, 19 June 2018, https://www.npr.org/2018/06/19/621435225/u-s-announces-its-withdrawal-from-u-n-s-human-rights-council. Accessed on 25 April 2021.

43 “US bans Sri Lanka army chief over war crimes”, Channel NewsAsia, 15 February 2020, https://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/asia/us-bans-sri-lanka-army-chief-over-war-crimes-12436878. Accessed on 25 April 2021.

44 Asanga Abeyagoonasekera, “America and China Dock in Sri Lanka”, op. cit.

45 Matthew Pennington, “The US wants to lure a strategic South Asian island nation away from China”, Business Insider, 2 February 2015, https://www.businessinsider.com/the-us-wants-to-lure-a-strategic-south-asian-island-nation-away-from-china-2015-2. Accessed on 30 April 2021.

-

More From :

More From :

-

Tags :

Tags :

-

Download PDF

Download PDF