Summary

The emphatic victory of the ruling Trinamool Congress (TMC) in the West Bengal Assembly election ushered in a third term for Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee. The TMC’s win was comprehensive, with Mamata’s popularity, the government’s welfare schemes and women’s vote being important factors. The result was a blow to the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), which had raised the stakes in the election outcome, with the prime minister and home minister expending considerable energy in the campaign. The result has burnished Mamata’s credentials and dented the BJP and the prime minister’s image in the short run.

Introduction

The sweep by the ruling Trinamool Congress (TMC) in the recently-held West Bengal Assembly election surprised many. Most analysts and exit polls had forecast a close contest between the TMC and the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) with hardly anyone predicting such an overwhelming victory for the TMC1.

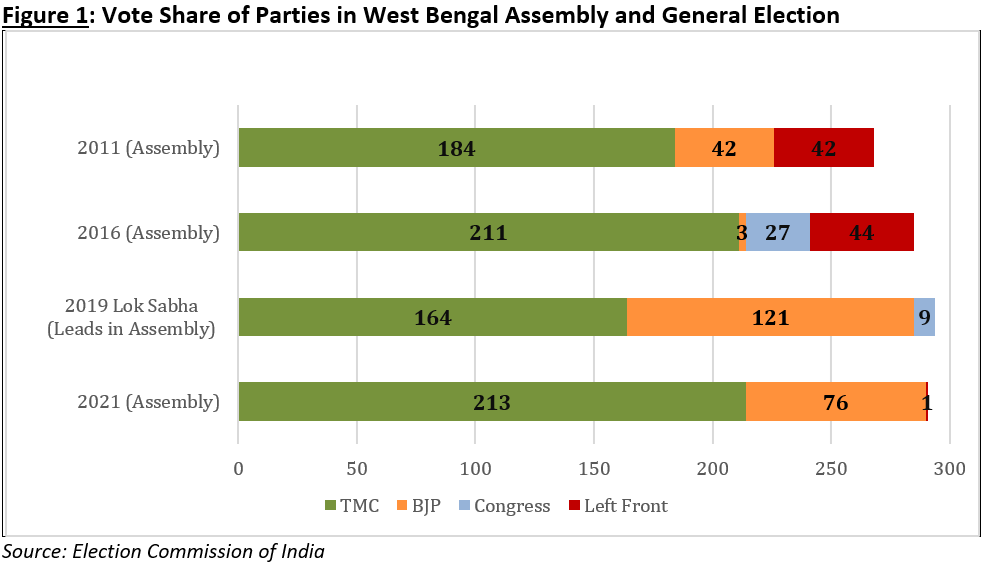

The TMC’s performance – by winning 213 seats out of 292 in the West Bengal Assembly that went to the polls with a vote share of nearly 48 per cent – bettered its showing in the 2016 Assembly election. The party’s victory was comprehensive, cutting across region, religion, caste, class and gender. For the BJP, which had banked on bettering its dramatic gains in the 2019 general election, the result was a blow to its ambitions of capturing a state that it has long prized. The BJP won 77 seats and 38 per cent of the vote share, which was considerably lower than the 121 Assembly segments, and 40 per cent vote share it had won in 2019, but a dramatic jump from the 2016 election (Figure 1). However, the BJP won with a very narrow margin – less than 5,000 votes – in 22 constituencies in contrast to the TMC, which had narrow victories in 13 constituencies. Hence, a small swing in votes could have further reduced the BJP’s tally. That the prime minister and home minister were so focused on the month-long, eight-phase Bengal elections, despite a raging pandemic, underlined the importance of winning the state, but was also a poor reflection on the party high command’s priorities.

Unpacking the TMC Victory

The TMC’s win was based on several factors, some of which were more apparent before the election and others that became more obvious after the result.

The popularity of Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee, who completed two terms in 2021, was never in doubt and was apparent in most pre-poll surveys and to those on the ground. In contrast, the absence of a chief ministerial face for the BJP, which has become standard for the party in most states, played into the TMC’s hands. While there was some speculation about local BJP leaders like the party state president Dilip Ghosh as a chief ministerial candidate, none of them were anywhere near Mamata’s popularity. According to the Lokniti-CSDS post-poll survey, Mamata was by a long stretch the most popular choice for chief minister. The survey also showed that 45 per cent of the respondents preferred Mamata to Modi and 29 per cent Modi over Mamata2. Such a gap is rarely seen in other states and meant that the BJP’s over-reliance on Modi did not work. Indeed, the BJP’s vicious personal campaign against Mamata, including the prime minister’s jibes, might have helped the TMC.

Besides Mamata’s popularity, there were four other factors that were critical to the TMC’s victory.

One, the welfare schemes put in place by the TMC government paid electoral dividends. According to CSDS-Lokniti, nearly 80 per cent of respondents said they had benefitted from the government’s popular Khadya Saathi programme, which provides free food ration; and nearly 50 per cent from Swasthya Sathi, which offers a health card issued in the name of the household matriarch, and Sabooj Sathi, a scheme to distribute bicycles to school students. The government’s pre-election Duare Sarkar (government at your doorstep) scheme was also extremely popular.

Two, women voters overwhelmingly backed Mamata and the TMC. The significance of the women vote was reflected in the TMC’s distribution of election tickets, with 50 of the 292 constituencies or 17 per cent fielding women candidates. Mamata, who is currently the only woman chief minister in India, has always been popular with women voters. Her popularity has been enhanced by welfare schemes specifically targetted at women. This was borne out in this election with half the women voters voting for the TMC compared to 37 per cent for the BJP3.

Three, the TMC successfully countered the BJP’s election campaign, spearheaded by Modi, Home Minister Amit Shah and a host of central leaders, by labelling it ‘bohiragato’ (a party of outsiders). Just before the election, the TMC unveiled its campaign slogan, ‘Bangla nijer meyekei chaay’ (Bengal wants its own daughter), which combined the centrality of Mamata in the party’s campaign even with the ‘outsider’ tag of the BJP. The TMC also used the slogan ‘Joy Bangla’ to counter the BJP’s divisive ‘Jai Shri Ram’ slogan and its Hindu nationalist rhetoric.

Finally, the collapse of the Left Front-Congress helped the TMC more than the BJP. In the 2019 general election, the BJP’s dramatic increase in vote share was partly due to the transfer of a bulk of the vote for the Left Front and Congress to the BJP. The combined vote share of the Left and the Congress fell from 38 per cent in the 2016 Assembly election to a mere 13 per cent in 2019. The Congress-Left vote share fell further in 2021 to 10 per cent. According to Lokniti-CSDS, the BJP attracted six-seven per cent fewer Left-Congress voters compared to 2019. It was also unable to attract a larger number of unattached voters compared to the TMC.

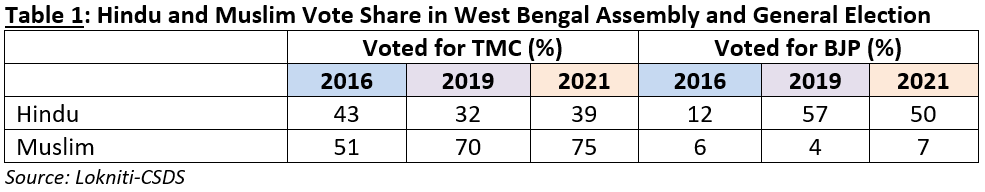

Why the BJP Did Worse than Expected

While all the above factors had an impact on the BJP’s performance, which was a huge improvement on 2016 but failed to better its 2019 showing, the results showed the limits of the BJP’s campaign of religious polarisation. Whereas in 2019, the BJP benefitted from a consolidation of the Hindu vote, there seems to have been a decline in the Hindu vote share for the party in 20214. The BJP saw a fall of seven per cent in its Hindu vote share and the TMC a similar increase. Conversely, Muslims, who constitute roughly 30 per cent of the state’s population, consolidated in greater numbers behind the TMC with nearly three quarters of them voted for the TMC in 2021 (Table 1).

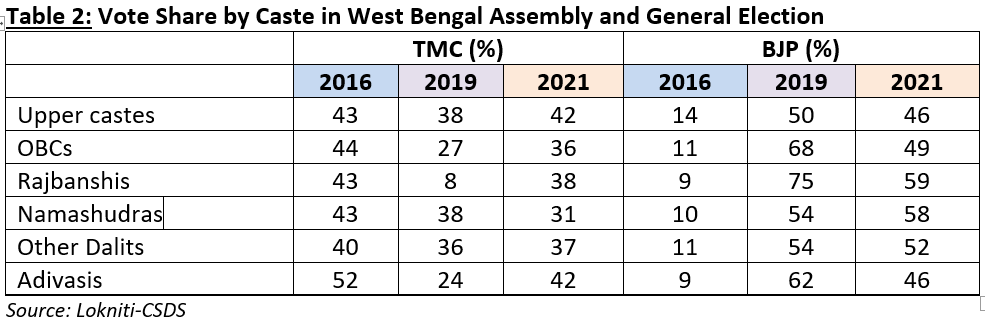

The BJP also saw a decline in support in 2021 among the Dalits, Adivasis and Other Backward Classes (OBCs) – seen by some as constituting ‘subaltern Hindutva’ – who had fuelled the BJP’s gains in 2019. The Lokniti-CSDS data shows that the TMC received much more votes from Dalits, Adivasis and OBCs in 2021 compared to 20195. Among the Rajbanshis, a sizeable Dalit community in Bengal, the TMC’s vote share jumped from eight per cent in 2019 to 38 per cent in 2021. For the Adivasis, the TMC’s vote share increased from 24 per cent in 2019 to 42 per cent in 2021. While the vote share was lower than the 2016 election, the TMC was able to make up considerable ground from 2019. It was only among the Namashudras, whom the BJP wooed assiduously using the Citizenship Amendment Act plank, that the party continued to hold on to its popularity (Table 2).

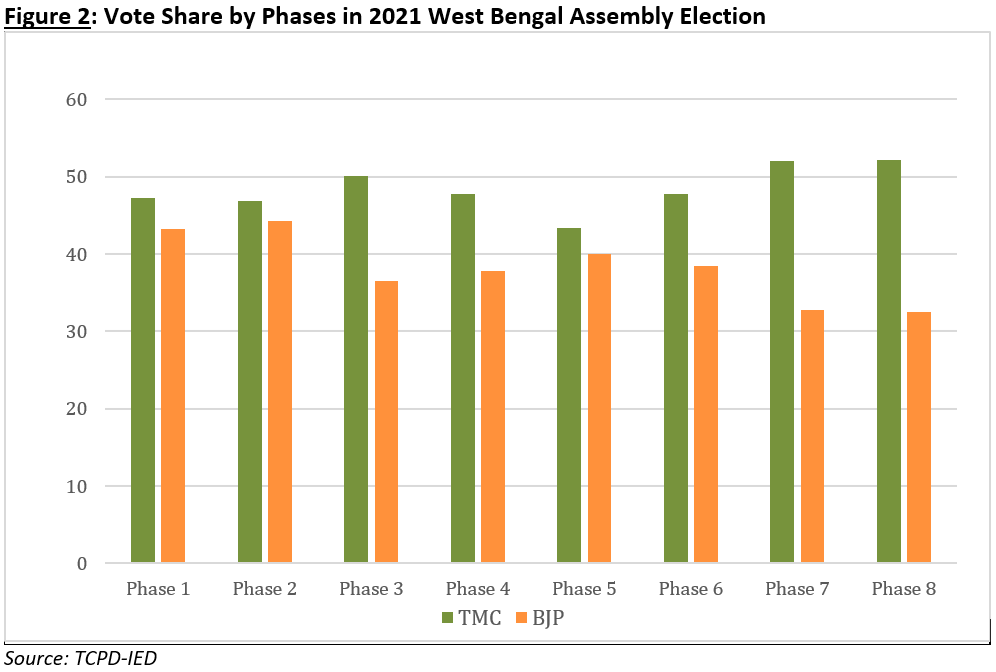

The eight-phase election, which many felt was meant to aid the BJP and its star campaigners, also did not work6. Lokniti-CSDS found that nearly a quarter of voters decided very late on whom to back. Of these, over half voted for the TMC compared to 33 per cent for the BJP. The TMC was also ahead of the BJP in every phase of the election with the gap increasing to nearly 30 per cent in the last two phases (Figure 2). This could have been due to the impact of the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic which had already become apparent as well as the negative publicity that the Centre and Modi were getting over their handling of the crisis. The prime minister had to cancel his rallies in the last two phases, possibly handicapping the BJP, which usually gets a last-minute bounce from Modi’s campaigning.

Other moves like inducting and fielding several defectors from TMC to cover the organisational deficiencies of the BJP backfired. Of the 34 defectors (28 from the TMC) whom the BJP fielded, only five won7. One of the most prominent defectors, Suvendu Adhikari, did a giant-killing act by defeating Mamata from Nandigram. But Adhikari, who used to oversee the TMC’s affairs in Medinipur, was not that successful in delivering other seats in the area to the BJP. Similarly, the move to make prominent faces, including member of parliament (MP) and minister Babul Supriyo, former nominated Rajya Sabha MP Swapan Dasgupta and sitting MP Locket Chatterjee, contest the Assembly elections did not pay off. All three lost. Most of the film stars and other celebrities, whom the BJP had given election tickets, also lost.

Despite its defeat, there was a silver lining for the BJP. It has firmly established itself as the primary opposition party in the state. It also retained seats in parts of Bengal, especially in north Bengal and some border constituencies in eastern and western Bengal, where it had gained a foothold in 20198.

Conclusion

The West Bengal result confirmed the divergence between national and state elections in India. The BJP has usually won a significantly lower vote share in Assembly elections held over the last two years compared to the general elections. Bengal was no exception.

The Bengal win has, however, burnished Mamata’s credentials since very few chief ministers have been voted back for a third term with such a resounding majority. The victory was even more noteworthy because of the enormous resources put into the campaign by the BJP. Some are already touting Mamata as the face of a federal front of regional parties in the 2024 general elections and the TMC’s strategy as a template to defeat the BJP9. However, such efforts have tended to founder on a lack of coherence among political parties and competing ambitions of regional leaders.

For Bengal, the results put in place a stable government with a strong mandate. However, the political violence that is a recurrent feature of the state’s politics – what Dwaipayan Bhattacharya called the effect of “party society”10 – has continued unabated. Indeed, with the BJP in opposition and likely to continue with its strategy of communal polarisation, the violence could escalate11. There were reports of political clashes in the aftermath of the election results with some of the incidents given a communal twist. Several of these reports were subsequently shown to be fake news12.

Another factor is the role of West Bengal Governor Jagdeep Dhankad, who, even by the standards of BJP-appointed governors, has taken a pronounced partisan and adversarial stance against the state government. Indeed, his actions call to scrutiny the constitutional role of governors in India. At the time of writing, Dhankad had given his consent to the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI), when West Bengal and the country was reeling from the pandemic, to prosecute two TMC ministers – a member of the legislative assembly and a former mayor of Kolkata – in a bribery case dating back to 201613. This has led an analyst to say the governor is spearheading the “political opposition” in the state14. However, two prominent defectors from the TMC to the BJP – Suvendu Adhikari and Mukul Roy, who were also implicated in the case – were not prosecuted. This has prompted questions regarding the impartiality of the CBI.

Finally, does the West Bengal result say anything about the popularity of Modi and the national dominance of the BJP? While undeniably the outcome was a blow to the BJP’s ambitions to topple Mamata and expand its reach in eastern India, it might not have significant impact on national politics15. What would be more worrisome for the BJP and Modi are the catastrophic effects of the COVID-19 second surge and the government’s lack of preparedness. This probably had an impact on the last two phases of the Bengal elections and could well be a factor in the crucial Uttar Pradesh Assembly election in 2022.

. . . . .

Dr Ronojoy Sen is a Senior Research Fellow and Research Lead (Politics, Society and Governance) at the Institute of South Asian Studies (ISAS), an autonomous research institute at the National University of Singapore. He can be contacted at isasrs@nus.edu.sg. Ms Kunthavi Kalaichelvam, a Research Trainee at ISAS, assisted him with the data visualisation. The author bears full responsibility for the facts cited and opinions expressed in this paper.

Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons

1 ‘West Bengal exit polls 2021: State headed for hung assembly, predict exit polls’, The Times of India, 1 May 2021. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/west-bengal-exit-poll-2021-resultsliveupdates/liveblog/82301468.cms.

2 Gilles Verniers, Basim-u-Nissa, Mohit Kumar and Neelesh Agrawal, ‘Bengal verdict: 25 charts show how the Trinamool conclusively beat the BJP’, scroll.in, 6 May 2021. https://scroll.in/article/994085/bengal-verdict-25-charts-show-how-the-trinamool-conclusively-beat-the-bjp.

3 Sanjay Kumar, ‘West Bengal Assembly Elections | Women rally behind Trinamool’, The Hindu, 6 May 2021. https://www.thehindu.com/elections/west-bengal-assembly/women-rally-behind-trinamool-finds-csds-lokniti-survey/article34494083.ece.

4 Suhas Palshikar, Shreyas Sardesai, Jyotiprasad Chatterjee, and Suprio Basu, ‘West Bengal Assembly Elections: The limits to polarisation in Bengal’, The Hindu, 6 May 2021. https://www.thehindu.com/elections/west-bengal-assembly/csds-lokniti-survey-the-limits-to-polarisation-in-bengal/article34494009.ece.

5 Shreyas Sardesai, ‘West Bengal Assembly Elections: Subaltern Hindutva on the wane?’, The Hindu, 6 May 2021. https://www.thehindu.com/elections/west-bengal-assembly/csds-lokniti-survey-finds-whether-subaltern-hindutva-is-on-the-wane/article34494129.ece.

6 Ronojoy Sen, ‘Bengal battle shows that for Indian democracy, elections matter more than accountability, governance’, Scroll.in, 26 April 2021. https://scroll.in/article/993186/bengal-battle-shows-that-for-indian-democracy-elections-matter-more-than-accountability-governance.

7 ‘Only 5 of 34 BJP candidates who won changed their party just before Assembly election’, Anandabazar Patrika, 12 May 2021. https://www.anandabazar.com/west-bengal/only-5-of-34-bjp-candidate-won-who-changed-thier-party-just-before-assembly-electtion-dgtl/cid/1280699.

8 https://thepolitics.in/dataviz/electoral-state-maps.

9 Neelanjan Sircar, ‘The Bengal model to counter the BJP’, Hindustan Times, 2 May 2021. https://www.hindustantimes.com/opinion/the-bengal-model-to-counter-the-bjp-101619971740348.html.

10 Dwaipayan Bhattacharyya, ‘Of Control and Factions: The Changing ‘Party-Society’ in Rural West Bengal’, Economic & Political Weekly, 44:9, 2009. https://www.epw.in/journal/2009/09/local-government-rural-west-bengal-special-issues-specials/control-and-factions.

11 Dwaipayan Sen, ‘Memories of 1946 Great Calcutta Killings Can Help Us Understand Violence in Today’s Bengal’, The Wire, 2 October 2018. https://thewire.in/communalism/1946-great-calcutta-killings-west-bengal.

12 Alishan Jafri, ‘Fake News and Communal Incitement add fuel to post-poll fire in West Bengal’, The Wire, 5 May 2021. https://thewire.in/politics/west-bengal-post-poll-violence-fake-news-communalism.

13 Ravik Bhattacharya and Santanu Chowdhury, ‘Narada bribery case: 2 ministers, 1 MLA arrested, Mamata rushes to CBI office’, The Indian Express, 17 May 2021, https://indianexpress.com/article/cities/kolkata/firhad-hakim-among-tmc-leaders-detained-by-cbi-in-narada-case-7318174/.

14 Shoaib Daniyal, ‘In West Bengal the apolitical governor is now the main political opposition’, Scroll.in, 2 May 2021. https://scroll.in/article/960728/in-west-bengal-the-apolitical-governor-is-now-the-main-political-opposition.

15 Diego Maiorano, ‘India’s State Election Results: Implications for the BJP’, ISAS Insights No. 663, 14 May 2021. https://www.isas.nus.edu.sg/papers/indias-state-election-results-implications-for-the-bjp/. Also see Rahul Verma, ‘The five lessons from five Assembly polls’, Hindustan Times, 2 May 2021. https://www.hindustantimes.com/opinion/the-five-lessons-from-five-assembly-polls-101619974318166.html.

-

More From :

More From :

-

Tags :

Tags :

-

Download PDF

Download PDF