Summary

In March and April 2021, four important Indian states went to the polls. The results have been disappointing for India’s ruling party, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). Since most voters expressed their preferences by voting before the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic became fully evident, the results are not an indication of the voters’ perception of the management of the pandemic. However, the behaviour of the government and of Prime Minister Narendra Modi during the electoral campaign might have dented his popularity significantly, particularly among the urban middle classes.

Introduction

In March and April 2021, four important state elections (in addition to an election in the Union Territory of Puducherry) took place. The states that went to polls were Assam in the North-East; West Bengal in the East; and Kerala and Tamil Nadu in the South. This paper looks at the results with a particular focus on the performance of India’s dominant party, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).

What do the results mean for Narendra Modi’s party? What are the implications of the results for national politics? And what challenges does the party face ahead? The paper will first present a snapshot of the results in the four states and identify key medium-term trends. It will then reason through some of the implications of the votes in the context of the current COVID-19 crisis.

The Results and Medium-term Trends

The results of the elections are presented in Tables 1 to 4.1

Table 1: Assam Election Results 2021

| Alliance | Party | Seat Share | Seat Share Difference from 2016 |

|---|---|---|---|

| NDA (incumbent) | BJP | 60 | 0 |

| AJP | 9 | -5 | |

| NDA (incumbent) | INC | 29 | -3 |

| AIUDF | 16 | +3 | |

| Others | 1 | – |

NDA = National Democratic Alliance; UPA = United Progressive Alliance; AGP = Asom Gana Parishad; INC = Indian National Congress; AIUDF = All India United Democratic Front

Table 2: West Bengal Election Results 2021

| Party | Seat Share | Seat Share Difference from 2016 |

|---|---|---|

| AITC (incumbent) | 213 | -1 |

| BJP | 77 | +74 |

| INC | 0 | -44 |

| Others | 2 | – |

AITC = All India Trinamool Congress

Table 3: Kerala Election Results 2021

| Party | Seat Share | Seat Share Difference from 2016 |

|---|---|---|

| LDF (incumbent) | 93 | +7 |

| UDF | 40 | 0 |

| Others | 0 | – |

LDF = Left Democratic Front; UDF = United Democratic Front

Table 4: Tamil Nadu Election Results 2021

| Alliance | Party | Seat Share | Seat Share Difference from 2016 |

|---|---|---|---|

| DMK+ | DMK | 133 | +33 |

| INC | 18 | +11 | |

| Others | 8 | – | |

| ADMK+ (incumbent) | ADMK | 66 | -59 |

| BJP | 4 | +4 | |

| Others | 5 | – |

DMK = Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam; ADMK = All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam

At first sight, the results are not disappointing for the BJP. First, it retained power in Assam, a key state that somewhat facilitates its expansion in the North-East of the country. Second, it achieved a formidable result in West Bengal, where the party barely had a presence in the previous Legislative Assembly, and secured the role of main opposition party. Given the complete collapse of the Congress party and the Left Front in the state, this achievement augurs well for the BJP’s future in West Bengal. Third, while failing to obtain any seat in Kerala, the BJP put a foot in Tamil Nadu, from where it did not have any representatives for two decades. Given the poor state of the AMDK – which is going through a seemingly neverending leadership struggle after the demise of former Chief Minister Jayalalithaa in 2016 – a more prominent (if junior) role for the BJP in Tamil Nadu cannot be ruled out.

However, when put into context, it is difficult not to see these as little more than consolation prizes for two important reasons. First, the BJP had invested so much in West Bengal – in terms of human, financial and political resources – that winning the state amounted to “an emotional project for the party”.2 The Election Commission had stretched the West Bengal polls over as many as eight phases (other large states like Tamil Nadu and Kerala voted in one day only), which was thought to favour the BJP by maximising the ‘Modi factor’.3

In fact, Modi himself addressed about 20 large rallies, while Home Minister Amit Shah spoke at more than 50 events, signalling the importance of the state for the BJP leadership. The party had also welcomed many defectors from the ruling TMC in an attempt to somewhat artificially boost its organisation on the ground. This came at a significant cost for the local BJP unit, whose cadres and leaders were often superseded by the new entrants.4 Finally, and more eventfully, the BJP, as well as other parties, continued their electoral campaigns almost through the end; they stopped on 22 April 2021 when COVID-19 cases detected nationally were over 300,000 daily. It is likely that large-scale rallies (those addressed by Modi and Shah were particularly large) turned into super-spreader events, as the spikes in cases in West Bengal (as well as in other states that went to polls) suggest.5 In other words, the BJP left no stones unturned to win the West Bengal elections but failed. Moreover, it fell short of the 100 seats mark, which was seen by many as the minimally acceptable performance for the party.

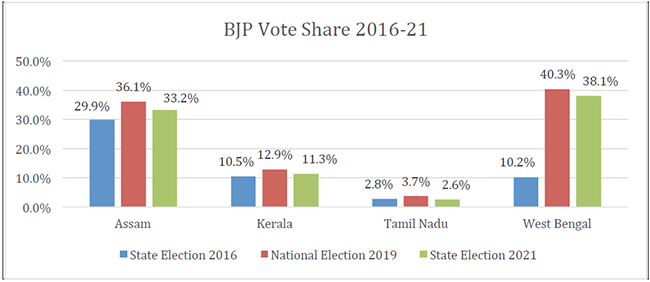

A second reason for concern for the BJP is that this round of state elections confirmed the ‘iron law’ of state politics post-2014: this is that the vote share of the BJP drops significantly from the national to the state elections (Figure 1).6 This suggests that one of the main, if not the main, contributing factors to the BJP’s dominance is Modi. At the state level, however, this factor helps but cannot overcome the absence of popular state leaders or chief ministerial candidates, who, as a rule, are not promoted by the Modi-Shah’s BJP. In the context of a COVID-19 second wave, which threatens to erode Modi’s invincible aura, this might become a serious cause for concern for the BJP, as can be seen in the next section.

Figure 1: BJP’s vote share 2016-21 in Assam, Kerala, Tamil Nadu and West Bengal

Source: Chart constructed by ISAS’ Research Analyst, Ms Divya Murali, using data from the Trivedi Centre for

Political Data at Ashoka University: https://lokdhaba.ashoka.edu.in/.

Implications

The four states that went to polls are radically different, with their own distinctive party systems and political actors. The BJP was the protagonist in two states (Assam and West Bengal) and little more than a spectator in the two others (Kerala and Tamil Nadu). For these reasons, it is difficult to extract a national message from the verdicts. Analysts of postpoll survey data have in fact spoken of a round of elections largely determined by local factors.7

The data shown in Figure 1 show that on the one hand, the BJP’s performance, particularly in Assam and West Bengal, has been truly remarkable, on the other, they show the enduring fragility of the BJP at the state level, which stunts its political dominance, and might contain the seeds for the erosion of its hegemony at the centre as well.8 This is also true from an institutional point of view, as the BJP is set to decrease its members in the Upper House (who are largely nominated by the state assemblies). This will increase the leverage of the opposition parties and their influence over national policy.

More than the results themselves – most voters voted before the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic became fully evident – it is the behaviour of the central government and the prime minister before and during the electoral campaign that might give us some signals on what the future might look like. In particular, there is a real possibility that a key element of trust connecting Modi to the voters has been, if not broken, at least seriously put into question.9

In 2020, Modi spared no effort to show himself in charge of the management of the pandemic. It was he who invited Indians to observe a ‘Janata curfew’ (people’s curfew) and celebrate healthcare workers in mid-March 2020. It was he who announced a strict national lockdown the same month; and it was he who prematurely celebrated victory over the virus in January 2021 when the number of cases reached its lowest point.10 While taking ownership of the battle against COVID-19 was beneficial to Modi’s popularity, it may now backfire.

We should not overestimate the possible backlash. Previous policies promoted by Modi that caused widespread suffering, especially among the lower classes like demonetisation in November 2016 or the national lockdown in 2020, did not result in any significant dent in Modi’s popularity, even among the social strata that suffered the most. However, the current situation is radically different for two reasons. First, the number of people affected virtually coincides with the entire population of the country. Second, the second wave has not spared the urban middle classes, Modi’s key base of social support.

The urban middle classes are the most important opinion-making segment of the population. They write newspaper reports and editorials; they teach in schools; they post on social media and they are hosted in omnipresent television debates. The current crisis has hit this segment of the population hard, which, despite its privileged background, network and affluence, struggled to find an oxygen cylinder or a hospital bed. And most families will have had a member who has been seriously ill or died from COVID-19. This enormous amount of suffering and anxiety will likely have an impact on Modi’s leadership and popularity. According to Morning Consult’s Global Leader Approval Rating Tracker,11 Modi’s net popularity nearly halved between 4 May 2020 (70 per cent) and 4 May 2021 (36 per cent). The dip is particularly significant since 2 April 2021 when Modi’s popularity was at 52 per cent.

More fundamentally from a political point of view, the current crisis showed to the urban middle classes in crystal clear terms that India is still very far from the status of a developed economy that their privileged status had made them believe. Modi had constructed his political persona around the idea that he was the strong leader that the country needed to build a ‘New India’ that could leave its impoverished past behind. But seven years after his election, the country has found itself on its knees, also thanks to some very questionable policy choices that he made. In particular, if one judges from editorials in the mainstream media, the urban middle classes have not missed the organisation of mass rallies in West Bengal as well as the go-ahead that the government gave to organise the Maha Kumbh Mela – a Hindu festival held every 12 years in North India – one year in advance. According to a report published by a very reputable magazine, The Caravan, the BJP decided to go ahead with the Kumbh without significant restrictions, which eventually attracted tens of millions of pilgrims around Haridwar in the state of Uttarakhand, mainly because it did not want to antagonise a powerful organisation of Hindu priests just a few months before the elections in Uttar Pradesh (which will happen in early 2022).12

Both these episodes highlight a crack in Modi’s carefully constructed image that has sustained his enormous popularity – of a leader disinterested in his political career who would put the good of the country above anything else. This might be an important lens through which the urban middle classes will see, write and talk about Modi over the next few months.

Three caveats should be kept in mind. First, the urban middle classes, however important for the formation of political opinions, are a numerically small segment of the population. Electorally, they matter only in a limited way. However, it should also be considered that the BJP’s dominance over India relies on its ability to secure a majority on its own. A small dip in the party’s vote share might result in quite a significant drop in the number of parliamentary seats.

Second, the next general elections are still far away. And Modi is an extremely able politician, who is able to listen and capture the public mood better than anyone else at the moment. The Uttar Pradesh elections of early 2022 will be an important turning point to see how the public has reacted to the management of the pandemic. But even if the BJP suffers there, there is no guarantee that Modi will not be able to find new political resources to spend in 2024 when the general elections take place.

Finally, there is a lack of opposition. The state elections decimated the Congress party even more: it lost in both states where it had a chance to win (Assam and Kerala) and failed to conquer a single seat in West Bengal, where it was a significant presence until not long ago. The only opposition party that emerged strengthened from the round of state election is the Trinamool Congress, whose leader, Mamata Banerjee, is now the only credible face to guide an anti-BJP front. However, such attempts have failed in the past, largely because of the difficulty of coordinating a multi-state alliance across radically different parties often led by incompatible leaders.

. . . . .

Dr Diego Maiorano is a Research Fellow at the Institute of South Asian Studies (ISAS), an autonomous research institute at the National University of Singapore (NUS). He can be contacted at dmaiorano@nus.edu.sg. The author bears full responsibility for the facts cited and opinions expressed in this paper.

Photo credit: Wikipedia

1 All data used to construct Tables 1 to 4 are taken from the website of the Election Commission of India, https://eci.gov.in/. Accessed on 10 May 2021.

2 Rahul Verma, ‘The five lessons from five assembly polls’, Hindustan Times, 22 May 2021, https://www.hindustantimes.com/opinion/the-five-lessons-from-five-assembly-polls-101619974318166.html.

3 Ronojoy Sen, ‘Mamata faces Strong BJP Challenge in Bengal’, ISAS Insights No. 658, 26 March 2021, https://www.isas.nus.edu.sg/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/658.pdf.

4 Shoaib Daniyal, ‘BJP’s fixation with TMC defectors sees party shoot itself in the foot in Singur’, Scroll.in, 8 April 2021, https://scroll.in/article/991488/bjps-fixation-with-tmc-defectors-sees-party-shoot-itself-in-thefoot-in-singur.

5 ‘Fact Check: Is Amit Shah Right to Say Elections Can’t be Blamed for COVID Spike?’, The Wire, 19 April 2021, https://thewire.in/government/amit-shah-elections-west-bengal-maharashtra-covid-cases-spike-factcheck.

6 Diego Maiorano, ‘The BJP at the Centre and in the States: Divergence, Big Time’, ISAS Brief No. 749, 20 February 2020, https://www.isas.nus.edu.sg/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Maiorano-The-BJP-at-thecentre-and-in-the-states-JV.pdf.

7 Suhas Palshikar, Sanjay Kumar, Shreyas Sardesai and Sandeep Shastri, ‘Local factors determine electoral outcomes in States’, The Hindu, 4 May 2021, https://www.thehindu.com/opinion/op-ed/local-factorsdetermine-electoral-outcomes-in-states/article34475075.ece.

8 James Manor, ‘A New, Fundamentally Different Political Order: The Emergence and Future Prospects of “Competitive Authoritarianism” in India’, Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 56, No. 10, https://www.epw.in/engage/article/new-fundamentally-different-political-order.

9 Asim Ali, ‘How the Covid-19 second wave has damaged Modi’s personality cult even among his loyal followers’, Scroll.in, 11 May 2021, https://scroll.in/article/994577/how-the-covid-19-second-wave-hasdamaged-the-formative-elements-of-narendra-modis-personality-cult.

10 ‘PM Modi cherishes India’s dual victory over Covid-19 and Australia’, Times of India, 22 January 2021, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/home/education/news/pm-modi-cherishes-indias-dual-victory-overcovid-19-and-australia-praise-young-india/articleshow/80402121.cms.

11 Global Leader Approval Rating Tracker, https://morningconsult.com/form/global-leader-approval.

12 Srishti Jaswal, ‘BJP fired ex-Uttarakhand chief minister TS Rawat for restricting Kumbh gatherings’, The Caravan, 8 May 2021, https://caravanmagazine.in/politics/bjp-fired-ex-uttarkhand-chief-ministertrivendra-singh-rawat-restricting-kumbh-gatherings.

-

More From :

More From :

-

Tags :

Tags :

-

Download PDF

Download PDF