Summary

The Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) was re-elected in Delhi with an overwhelming mandate, winning 62 seats compared to the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)’s eight. The AAP’s victory was a triumph of its campaign message on governance issues. In contrast, the BJP’s polarising campaign failed to deliver. The Delhi verdict has lessons for both the BJP and regional parties in the coming elections.

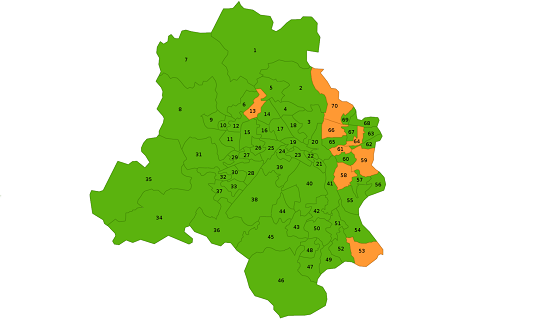

The Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) and Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal were voted back to power with a resounding majority in the Delhi Assembly election. The AAP won 62 seats in the 70-member Delhi Assembly. The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) came a distant second with eight seats while the Congress drew a blank, making the contest essentially a bipolar one.

The AAP’s victory was remarkable on several counts. It polled almost 54 per cent of the popular vote, similar to what it did in 2015. This is unique in India’s recent electoral history with no party being re-elected with more than 50 per cent vote share in successive Assembly elections. Furthermore, the AAP did not win a single seat in Delhi in the 2019 general election, where its vote share was 18 per cent compared to 56 per cent for the BJP. Indeed, in 2019, the AAP stood third behind the Congress in terms of vote share. However, in less than a year, the AAP’s vote share spiked by 36 per cent whereas the BJP’s fell steeply by around 18 per cent, which meant that a third of those who voted for the BJP in 2019 switched to the AAP. This occurred despite the BJP running a vitriolic campaign – revolving around issues such as the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) – where all its major leaders, including Prime Minister Narendra Modi, campaigned extensively. In fact, Home Minister Amit Shah addressed around 50 public meetings during the course of the campaign.

What explains the overwhelming mandate for a second time for the AAP?

First, the election campaigns of the BJP and the AAP were very different. The AAP ran a positive campaign, highlighting its performance in improving the quality of government schools and health clinics, providing subsidised water and electricity and ensuring free public transport for women. The BJP, on the other hand, preferred to campaign on divisive issues like the CAA and the ongoing protests against the legislation. Two senior BJP leaders, including a central minister, were censured by the Election Commission for hate speech during the campaign. A Lokniti-CSDS survey conducted before the election found that a clear majority of respondents chose development and governance as their priority while only seven per cent said that ideological issues, such as the CAA, mattered for the election. Significantly, the AAP did not challenge the BJP’s ideological narrative but chose to steer clear of it.

Second, Kejriwal’s popularity and the absence of a chief ministerial face for the BJP had an enormous impact on the election outcome. According to the Lokniti-CSDS survey, nearly half the respondents were satisfied with Kejriwal. This has something to do with the makeover of Kejriwal from an anti-establishment protester to an able administrator. The BJP, in contrast, preferred to bank on Modi’s charisma. While Modi is popular in Delhi, that was not enough to sway the voters when it came to the Assembly election.

Third, the Delhi election, once again, showed that state polls are decided on local issues and throw up verdicts that can be quite different from the general election. While this has been the case earlier, the gap between national and state elections has become starker in recent times. Thus, despite the BJP’s dominant performance in the 2019 general election, it has done poorly in several state elections from end-2018.

The impact of the AAP’s spectacular victory can be read in different ways. One is that the BJP and Modi’s popularity is slipping. That would not be entirely correct. The Delhi election result is a reminder that Assembly polls have a different narrative from that of general elections. National issues, such as Kashmir or the CAA, have less resonance in Assembly elections. More importantly, the Modi magic is incapable of carrying the BJP through, especially if it faces a strong regional party with a credible chief ministerial candidate. This was evident from the Lokniti-CSDS survey, which found that half the respondents in Delhi were satisfied with Modi but chose to go with Kejriwal. This dichotomy is present in other Indian states too.

Another way to decode the Delhi verdict is to see a rejection of the BJP’s ideological agenda. However, that too has its problems since the AAP did not take on the BJP’s highly charged and ideological campaign and instead emphasised its own record in the last five years. Indeed, on several controversial issues, such as the abrogation of Kashmir’s special status, the AAP has sided with the BJP. On other issues, such as the anti-CAA protests, the AAP chose to maintain its distance. This worked well for the AAP since many Delhi voters, including those who voted for the AAP, were in favour of the CAA. While this strategy paid off in a small and relatively well-off state like Delhi, it might not work in larger states like Bihar or West Bengal where identity issues matter much more.

The AAP’s win in Delhi has lessons for regional parties, which are likely to play up governance and welfare schemes in the coming elections. As for the AAP, it does not seem to be harbouring national ambitions. For the BJP, the Delhi verdict could force a rethink on its strategy of focussing on national as well as divisive issues in Assembly elections.

Dr Ronojoy Sen is a Senior Research Fellow and Research Lead (Politics, Society and Governance) at the Institute of South Asian Studies (ISAS), an autonomous research institute at the National University of Singapore (NUS). He can be contacted at isasrs@nus.edu.sg. The author bears full responsibility for the facts cited and opinions expressed in this paper.

-

More From :

More From :

-

Tags :

Tags :

-

Download PDF

Download PDF