Xi Jinping in Myanmar: Complex ‘Pauk-Phaw’ Relations in Operation

Iftekhar Ahmed Chowdhury

22 January 2020Summary

The relationship between Myanmar and China has, in the past, been fraught with complexities. China may be taking advantage of Myanmar’s current global adversities to push its agenda hard. It may be poised to achieve its objectives. For this, it seems prepared to ride roughshod over regional and global sentiments.

‘Pauk-Phaw’, a Myanmarese term, usually means ‘fraternal’. It is often used to describe relations between siblings. In Myanmar, it has often been used to refer to its Chinese connections. Most recently, and significantly, it was a political vocabulary that no less a person than Chinese President Xi Jinping relied on when he penned an article published in a Myanmarese newspaper on 16 January 2020, just on the eve of his recent visit to Myanmar. Somewhat grandiosely, the piece was entitled “Writing a New Chapter in our Millennia-old Pauk-Phaw Friendship”. Xi went on to state that it was an apt description of the fraternal sentiments between our two peoples, whose ties date back to ancient times.

That could be an exaggeration. Bilateral relations in the past have not been as smooth as the article makes them to be. Historically, communist groups within that country had sought and obtained solace and succour from such militants. Indeed, just prior to the visit, a Chinese senior emissary, Sun Guoxiang, had met such groups near the border. One result of the meeting was statements of welcome to the Chinese president issued by the ethnic insurgents. This also signalled the kind of power Beijing still wields over those who can be potential trouble-makers for the Myanmar regime.

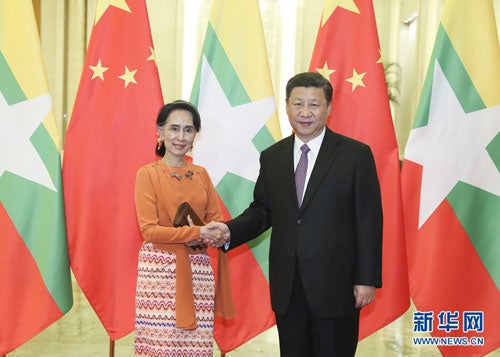

However, for Beijing, the visit was well timed. Myanmar was caught between the devil and the deep blue sea. The leadership is reeling from the criticisms faced particularly from western countries with regard to the conduct of the military in the Rakhine State, mainly with regard to the Rohingya refugees who have fled to Bangladesh. The fall from grace in western eyes of Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, the most senior elected leader in recent times, has been striking. Many senior generals are under sanction. The government had been dragged to the international court in the Hague on allegations of severe human rights violations. For Naypyidaw, the window of manoeuvrability vis-à-vis Beijing had shrunk. China was the alternative source of support it could scarcely ignore.

Xi was also careful to pander to Myanmarese sensibilities. In his article, he listed three main subjects that would be central to the discussions during his two-day visit to Myanmar. These would be: one, the Kyaukphyu Special Economic Zone; two, the China-Myanmar Border Economic Cooperation Zone; and three, the New Yangon City Project. These three are key to the now much-touted China-Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC), perhaps the second major flagship economic intervention of China in the region after the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, in a country that is clearly China’s most trusted global ally.

All these are a part of China’s massive global strategy, known as the Belt and Road Initiative, linking peoples, countries and continents in a gargantuan development scheme. Xi made no mention of the controversial Myitsone Dam, which had been an apple of discord between Myanmarese public opinion and China. The project, meant to produce 6,000 megawatts of power, signed during Xi’s previous visit as Vice President about a decade ago, was eventually all but cancelled in 2011 due to the huge public protests. If Xi saw it as a personal affront, he appeared to conceal it very effectively. There were other more lucrative prizes to be gained.

These lay in the 33 agreements the two sides inked. These spanned across the spectrum of infrastructure, energy and trade. Nothing was stated as to how the two planned to speed up the slow negotiations with the several armed ethnic groups. Though a concession agreement and a shareholders’ agreement were signed on the Kyaukphyu port in the Rakhine State, it was unclear if the final green signal was given by Naypyidaw. However, even if the ultimate consent was awaited, there was no doubt as to what the outcome would be! It is too critical to China’s interests. It would greatly enhance China’s presence in the Indian Ocean, also allowing its oil imports to by-pass Malacca.

Single-country visits by Xi, as the one to Myanmar, are a rare phenomenon. China’s need for access to the Indian Ocean through the CMEC was too central to its strategy to be derailed in any way by any possible wariness of India, for which ample causes existed. Nor did it allow any unhappiness on the part of Bangladesh, in adversarial relationship with Myanmar over the Rohingya issues, but nevertheless a friend of China, to stand in the way. In its difficult times in global politics, Myanmar would need China in the United Nations Security Council. That was reward enough for Aung San Suu Kyi. However, to the dispassionate observer, the ‘Pauk-Phaw’ relationship in Myanmar, now fully in Chinese bind, might appear woefully asymmetric.

….

Dr Iftekhar Ahmed Chowdhury is a Principal Research Fellow at the Institute of South Asian Studies (ISAS), an autonomous research institute at the National University of Singapore (NUS). He is a former Foreign Advisor (Foreign Minister) of Bangladesh. He can be contacted at isasiac@nus.edu.sg. The author bears full responsibility for the facts cited and opinions expressed in this paper.

-

More From :

More From :

-

Tags :

Tags :

-

Download PDF

Download PDF