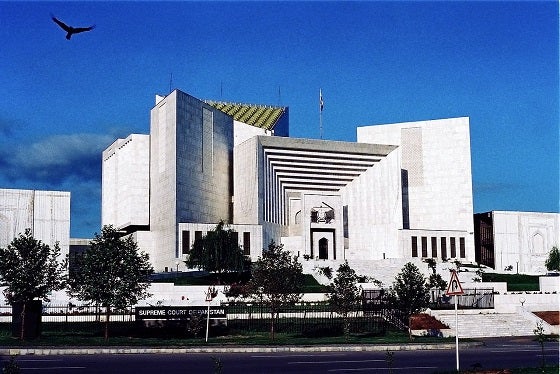

The Courts, the Army and the Government: The Tangled Triangle of Turmoil in Pakistan

Iftekhar Ahmed Chowdhury

3 December 2019Summary

The Judiciary in Pakistan is becoming increasingly interventionist. It is now impacting on both the elected political authority and the military brass. The paper examines its implications for Pakistan’s democracy and governance.

What is shaking the roots of the Pakistani ethos today does not emanate from actions of its violent extremists nor from the tumultuous politics of its polity, or from the possibility of an overt or covert military coup that has been a regular feature of the nation’s historical evolution, but from the mildly expressed but firmly held views of a judge committed to the values of the rule of law. He is Chief Justice Asif Saeed Khosa, an English-trained legal professional, who has in the past peppered his judgments with quotes from the poets, John Donne and Kahlil Gibran, celebrating the power of the people.

While Pakistan is generally viewed is a country where the military has ruled the roost, it is also replete with examples of judicial interventionism, often with profound consequences. Sometimes, these have sufficiently coincided with the interests of the military brass sufficiently to suspect collusion. An example is Chief Justice Muhammad Munir, who, in the mid-1950s, propounded the ‘Doctrine of Necessity’, later unabashedly used by the Army to legally justify its seizure of power. Munir drew upon the writings of the mediaeval jurist Henry de Bracton’s maxim that “which is otherwise not lawful is made lawful by necessity”. It has roots in the Latin legal principle, Salus Populi Suprema Lex, the well-being of the people is the supreme law, embodied in the ‘Second Treatise of Government’ of the philosopher, John Locke, often viewed as a great champion of democratic pluralism. Thereafter, the doctrine has been cited in many Commonwealth Courts.

While Pakistani military rulers continued to use the doctrine as a useful tool for decades, subsequently, the judiciary also stepped in to modify it, ruling that military take-overs of the kind effected by General Zia-ul-Huq was illegal (though pronounced after the dictator’s death). In a landmark judgment in 2009, Chief Justice Iftikhar Muhammad Chaudhry ruled that no judge can offer any support to the acquisition of power in any manner by any unconstitutional functionary through modes other than envisaged in the Constitution. This dealt a great moral blow to any future overt military coups. While it did not prevent General Pervez Musharraf’s take-over, it did come back to haunt this former president who is currently arraigned before a court in Islamabad on charges of ‘treason’ though given the ultimate political realities, a conviction with sentencing may be unlikely.

There is also growing consternation within Pakistan of the government’s authorisation of the arrest of a number of opposition leaders on corruption charges and censoring of the media. Such concerns were exacerbated when the government extended the army chief’s tenure by three years in August 2019. Prior to this, only one army chief has had his tenure extended by a civilian government. Bajwa’s extension was justified on the grounds that the “regional security environment”, namely, tensions with India over Kashmir and the potential withdrawal of American troops from Afghanistan, necessitated continuity.

The Courts have also been known to come down heavily on the politicians and elected governments when they have been viewed as having crossed red-lines. In 2012, Prime Minister Yousuf Raza Gillani became the first-ever head of the Cabinet to be convicted while still in office with contempt of court, being sentenced to be held till the rising of the Court, which, however, was more a technicality than reality, as it lasted barely 30 seconds! Of much greater consequence was the Supreme Court’s ousting from office of Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif in July 2017 on allegations of possessing assets “incompatible with his known sources of income”.

Fast forward to the present! It is well-known that Prime Minister Imran Khan is hand in glove with the Army, commanded by General Qamar Javed Bajwa. Indeed, the received wisdom is that the former is being kept propped up in office by General Bajwa’s support. Unsurprisingly, when General Bajwa’s retirement fell due on 29 November 2019, Imran Khan, well ahead in time, in fact on 19 August 2019, issued a notification, extending his tenure by another three years, citing “regional security environment”. The move was expected and no eyebrows were raised. Then, a couple of days prior to that date, a serial petitioner challenged the extension in the Court. Thereafter, thinking the better of it, he sought to withdraw his motion.

However, a shock of seismic proportions then rocked the country. Chief Justice Khosa rejected the petitioner’s withdrawal plea, taking cognisance of the case as it fell, in his view, within the domain of public interest under Article184 (3) of the Constitution.

At the hearings, the bench comprising him and two other judges, Justice Mazhar Alam Khan and Justice Syed Mansoor Ali Shah, observed that under Article 243, only the Commander-in-Chief, that is, President Arif Alvie, and not the prime minister, was the “appointing authority” of the Army Chief, and authorised to take any decisions in that regard. Also, it was the role of the “gallant armed forces” to confront the “security environment” and not that of any individual officer. Consequently, the judges suspended the notification and asked for a new one, with some suggestions. The government scrambled to redraft it, following which the Court ruled extending General Bajwa’s tenure for six months for now on the condition that the government legislate afresh the relevant terms and conditions during that period.

The three-day drama in Pakistan’s Supreme Court had several ramifications. First, the all-powerful military was now brought under the constitutional legal ambit, its uncontested authority dented in public perception. Second, indirectly, Imran Khan would benefit from the fact that General Bajwa would remain beholden to him for the rest of the latter’s term, bringing a greater equality in the relationship. And third, the fact that if the Court is able to have its way, no one would be above the law. The overall impact of these on Pakistan’s politics is likely to be positive.

….

Dr Iftekhar Ahmed Chowdhury is Principal Research Fellow at the Institute of South Asian Studies (ISAS), an autonomous research institute at the National University of Singapore (NUS). He can be contacted at isasiac@nus.edu.sg. The author bears full responsibility for the facts cited and opinions expressed in this paper.

-

More From :

More From :

-

Tags :

Tags :

-

Download PDF

Download PDF